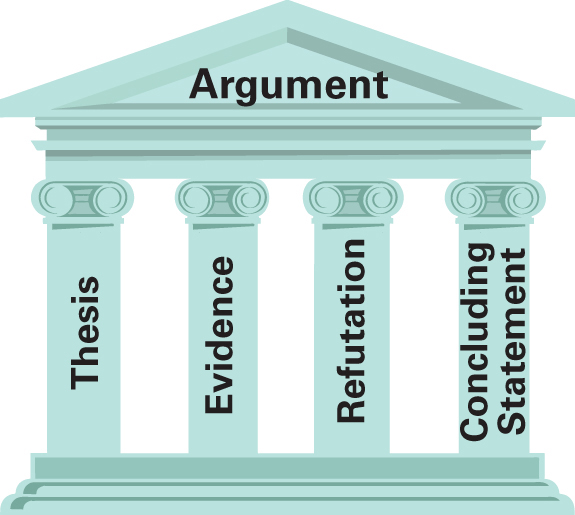

Structuring an Ethical Argument

In general, an ethical argument can be structured in the following way.

Introduction: Establishes the ethical principle and states the essay’s thesis

Background: Gives an overview of the situation

Ethical analysis: Explains the ethical principle and analyzes the particular situation on the basis of this principle

Evidence: Presents points that support the thesis

Refutation of opposing arguments: Addresses arguments against the thesis

Conclusion: Restates the ethical principle as well as the thesis; includes a strong concluding statement

![]() The following student essay contains all the elements of an ethical argument. The student takes the position that colleges should do more to help nontraditional students succeed.

The following student essay contains all the elements of an ethical argument. The student takes the position that colleges should do more to help nontraditional students succeed.

Grammar in Context

Subordination and Coordination

When you write an argumentative essay, you need to show readers the logical and sequential connections between your ideas. You do this by using coordinating conjunctions and subordinating conjunctions—words that join words, phrases, clauses, or entire sentences. Be sure to choose conjunctions that accurately express the relationship between the ideas they join.

Coordinating conjunctions— and, but, for, nor, or, so, and yet —join ideas of equal importance. In compound sentences, they describe the relationship between the ideas in the two independent clauses and show how these ideas are related.

“Colleges and universities are experiencing an increase in the number of nontraditional students, and this number is projected to rise.” (And indicates addition.) (para. 1)

“These students have a lot to offer, but often they don’t feel included.” (But indicates contrast or contradiction.) (3)

Subordinating conjunctions— after, although, because, if, so that, where, and so on—join ideas of unequal importance. In complex sentences, they describe the relationship between the ideas in the dependent clause and the independent clause and show how these ideas are related.

“Although these students enrich campus communities and provide new opportunities for learning, they also present challenges.” (Although indicates a contrast.) (1)

“Although many schools recognize that nontraditional students have unique needs, most schools ignore these needs and unfairly continue to focus on the ‘typical’ student.” (Although indicates a contrast.) (1)

“As long as these barriers to equal access exist, nontraditional students will always be ‘second-class citizens’ in the university.” (As long as indicates a causal relationship.) (4)

“If instructors want to be more inclusive, they can acknowledge diversity by engaging students in diverse ways of thinking and learning.” (If indicates condition.) (6)

![]() For more practice, see the LearningCurve on Coordination and Subordination in the LaunchPad for Practical Argument.

For more practice, see the LearningCurve on Coordination and Subordination in the LaunchPad for Practical Argument.

EXERCISE 16.6

EXERCISE 16.6

The following essay includes the basic elements of an ethical argument. Read the essay, and then answer the questions that follow it, consulting the outline on page 599 if necessary.

This essay was published in the Wall Street Journal on April 29, 2015.

DANIEL SULEIMAN

MORE THAN “MORAL COMPLICITY” AT AUSCHWITZ

On the opening day of his criminal trial in Lüneburg, Germany, on April 21 for complicity in the deaths of approximately 300,000 Jews, most of whom were Hungarian, former Waffen-SS officer Oskar Gröning conceded that he bears “moral” responsibility for the role he served at Auschwitz, the notorious concentration camp where he was stationed from 1942–44. But Mr. Gröning, who is 93, does not admit that he is guilty of crimes.1

“It is without question that I am morally complicit in the murder of millions of Jews through my activities at Auschwitz,” he told the court, according to the Guardian. “But as to the question whether I am criminally culpable, that’s for you to decide.”2

Mr. Gröning’s strategy of conceding one battle in an attempt to win a more important one is a common criminal-defense tactic. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who was convicted by a jury on April 8 for his role in the Boston Marathon bombings, is trying something similar.3

On the first day of the guilt phase of his trial, Tsarnaev’s lawyer admitted that Tsarnaev and his brother were responsible for the bombings and the murder of a university police officer. Why? Because by handing the government a victory in the guilt phase, Tsarnaev hopes to strengthen his argument, being made in the sentencing phase, that he should be spared the death penalty.14

Sometimes this strategy works. But sometimes it is merely all a defendant has. Should Mr. Gröning’s concession that he bears moral responsibility for the deaths at Auschwitz spare him a guilty verdict?5

The short answer is no. There are clearly situations in which moral failings do not, and should not, equate with criminal guilt. Adultery is commonly considered a moral failure in the U.S., but Americans are no longer prosecuted for it. Doing nothing while a neighbor’s house burns to the ground could result in feelings of moral guilt, but it is almost certainly not a crime. In an example closer to Mr. Gröning’s situation, someone who refused to hide a friend or neighbor as the Jews were being rounded up in Budapest might feel “morally complicit” in their subsequent deaths, but we would not consider him criminally responsible.6

Let us assume the facts are as Mr. Gröning contends—that he collected the belongings of incoming prisoners at Auschwitz, and witnessed atrocities, but that he did not personally participate in gassing innocent victims or, in his own horrifying example, beat to death an infant who had been left behind. We have no way of knowing whether these events occurred as he has told them, or if there were other instances in which Mr. Gröning directly participated in acts of murder. But it is indisputable, apparently even to Mr. Gröning himself, that he bears some moral responsibility for the deaths that occurred while he was at Auschwitz.7

So is he also guilty of crimes? The camps were not his idea. He didn’t, as far as we know, deliver anyone to the gas chamber. Maybe he even privately came to reject Nazi ideology.8

“So is he also guilty of crimes?”

I recognize that my judgment might be clouded by the fact that my mother, who was born in Budapest in 1939, could have been one of Oskar Gröning’s victims, had she and her parents not survived the war under assumed identities. Or because other members of my family did perish in concentration camps, perhaps while Mr. Gröning looked on. Yet I am trained to examine legal questions analytically and, as a purely legal matter, I do not accept Mr. Gröning’s argument, for it finds no support in common concepts of criminal law.9

By way of example, every day across the U.S., defendants are indicted for aiding and abetting others in the commission of their crimes, or serving as an accomplice, or participating with others in a criminal enterprise. These concepts are basic, and elastic. If I abhor bank robbery, but I nevertheless drive you to a local bank, where, dressed in a mask with a gun in your hand, you get out and rob the bank, you and I have both committed crimes. If I help route phone calls to a network of drug dealers, but never touch the stuff, I am still a criminal.10

And if I strip Holocaust victims on their way to the gas chamber of their last coins, because, as Mr. Gröning testified, “they didn’t need it anymore,” I am guilty. I am an accomplice to murder, a participant in a criminal enterprise. Caught up in activities of others’ design, perhaps, but guilty nonetheless.11

Ninety-three-year-old men are not ideal criminal defendants because their frailty lends them a sympathetic sheen. Mr. Gröning, with his walker, hardly resembles the SS officer and money-counter he once was. But there is no statute of limitations on atrocity, and his concession of moral guilt should not confuse anyone into thinking that he does not also share criminal responsibility for what occurred at Auschwitz.12

Identifying the Elements of an Ethical Argument

- Look up the definition of complicity. What does Gröning mean when he says, “I am morally complicit in the murder of millions of Jews” (para. 2)?

- What ethical principle does Suleiman apply in his essay? At what point in the essay does he state this principle? Why do you think he states it where he does?

- What is the thesis of this essay? In your own words, write it on the lines in the template below.

Despite his admission of moral guilt, ___________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________.

- According to Suleiman, what is the difference between moral guilt and legal guilt? Is it possible for a person to be morally complicit in murder but not criminally culpable? Explain.

- Where in the essay does Suleiman discuss possible objections to his thesis? Where does he concede that he may be biased? How effectively does he address these issues?

- What examples does Suleiman use to support his thesis? What other kinds of support could he have also used? Should he have used other support? Explain.

- In his essay, Suleiman employs all three appeals—logos, pathos, and ethos. Locate examples of each. How effective is each appeal? Explain.

- What ideas does Suleiman emphasize in his conclusion? Do you think that his conclusion is effective? Explain.

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

How Far Should Schools Go to Keep Students Safe?

Lawrence K. Ho/Getty Images

Go back to page 589, and reread the At Issue box, which gives background on how far schools should go to keep their students safe. Then, read the sources on the pages that follow.

As you read this source material, you will be asked to answer some questions and to complete some simple activities. This work will help you understand both the content and the structure of the selections. When you are finished, you will be ready to write an ethical argument that takes a position on the topic, “How Far Should Schools Go to Keep Students Safe?”

SOURCES

Brett A. Sokolow, “How Not to Respond to Virginia Tech — II,” p. 609

Brett A. Sokolow, “How Not to Respond to Virginia Tech — II,” p. 609 Jesus M. Villahermosa Jr., “Guns Don’t Belong in the Hands of Administrators, Professors, or Students,” p. 613

Jesus M. Villahermosa Jr., “Guns Don’t Belong in the Hands of Administrators, Professors, or Students,” p. 613 Timothy Wheeler, “There’s a Reason They Choose Schools,” p. 616

Timothy Wheeler, “There’s a Reason They Choose Schools,” p. 616 Greg Hampikian, “When May I Shoot a Student?,” p. 619

Greg Hampikian, “When May I Shoot a Student?,” p. 619 Todd C. Frankel, “Can We Invent Our Way Out of School Violence?,” p. 622

Todd C. Frankel, “Can We Invent Our Way Out of School Violence?,” p. 622 Alan Schwarz, “A Bid for Guns on Campuses to Deter Rape,” p. 625

Alan Schwarz, “A Bid for Guns on Campuses to Deter Rape,” p. 625 Isothermal Community College, “Warning Signs: How You Can Help Prevent Campus Violence” (brochure), p. 629

Isothermal Community College, “Warning Signs: How You Can Help Prevent Campus Violence” (brochure), p. 629 Amy Dion, “Gone but Not Forgotten” (poster), p. 633

Amy Dion, “Gone but Not Forgotten” (poster), p. 633

Inside Higher Ed published this essay on May 1, 2007.

BRETT A. SOKOLOW

HOW NOT TO RESPOND TO VIRGINIA TECH—II

If you believe the pundits and talking heads in the aftermath of the Virginia Tech tragedy, every college and university should rush to set up text-message-based early warning systems, install loudspeakers throughout campus, perform criminal background checks on all incoming students, allow students to install their own locks on their residence hall room doors, and exclude from admission or expel students with serious mental health conditions. We should profile loners, establish lockdown protocols, and develop mass-shooting evacuation plans. We should even arm our students to the teeth. In the immediate aftermath, security experts and college and university officials have been quoted in newspapers and on TV with considering all of these remedies, and more, to be able to assure the public that WE ARE DOING SOMETHING.1

Since when do we let the media dictate to us our best practices? Do we need to do something? Do we need to be doing all or some of these things? Here’s what I think. These are just my opinions, informed by what I have learned so far in the reportage on what happened at Virginia Tech. Because that coverage is inaccurate and incomplete, please consider these my thoughts so far, subject to revision as more facts come to light.2

“Since when do we let the media dictate to us our best practices?”

We should not be rushing to install text-message-based warning systems. At the low cost of $1 per student per year, you might ask what the downside could be? Well, the real cost is the $1 per student that we don’t spend on mental health support, where we really need to spend it. And, what do you get for your $1? A system that will send an emergency text to the cell phone number of every student who is registered with the service. If we acknowledge that many campuses still don’t have the most current mailing address for some of our students who live off-campus, is it realistic to expect that students are going to universally supply us with their cell phone numbers? You could argue that students are flocking to sign up for this service on the campuses that currently provide it (less than 50 nationally), but that is driven by the panic of current events. Next fall, when the shock has worn off, apathy will inevitably return, and voluntary sign-up rates will drop. How about mandating that students participate? What about the costs of the bureaucracy we will need to collect and who will input this data? Who will track which students have yet to give us their numbers, remind them, and hound them to submit the information? Who will update this database as students switch cell numbers mid-year, which many do? That’s more than a full-time job, with implementation already costing more than the $1 per student. Some students want their privacy. They won’t want administrators to have their cell number. Some students don’t have cell phones. Many students do not have text services enabled on their phones. More added cost. Many professors instruct students to turn off their phones in classrooms.3

Texting is useless. It’s useless on the field for athletes, while students are swimming, sleeping, showering, etc. And, perhaps most dangerously, texting an alert may send that alert to a psychopath who is also signed-up for the system, telling him exactly what administrators know, what the emergency plan is, and where to go to effect the most harm. Would a text system create a legal duty that colleges and universities do not have, a duty of universal warning? What happens in a crisis if the system is overloaded, as were cellphone lines in Blacksburg? What happens if the data entry folks mistype a number, and a student who needs warning does not get one? We will be sued for negligence. We need to spend this time, money, and effort on the real problem: mental health.4

We should consider installing loudspeakers throughout campus. This technology has potentially better coverage than text messages, with much less cost. Virginia Tech used such loudspeakers to good effect during the shootings.5

We should not rush to perform criminal background checks (CBCs) on all incoming students. A North Carolina task force studied this issue after two 2004 campus shootings and decided that the advantages were not worth the disadvantages. You might catch a random dangerous applicant, but most students who enter with criminal backgrounds were minors when they committed their crimes, and their records may have been sealed or expunged. If your student population is largely of non-traditional age, CBCs may reveal more, but then you have to weigh the cost and the question of whether you are able to perform due diligence on screening the results of the checks if someone is red-flagged. How will you determine which students who have criminal histories are worthy of admission and which are not? And, there is always the reality that if you perform a check on all incoming students and the college across the street does not, the student with the criminal background will apply there and not to you. If you decide to check incoming students, what will you do about current students? Will you do a state-level check, or a 50-state and federal check? Will your admitted applicants be willing to wait the 30 days that it takes to get the results? Other colleges who admitted them are also waiting for an answer. The comprehensive check can cost $80 per student. We need to spend this time, money, and effort on the real problem: mental health.6

We should not be considering whether to allow students to install their own locks on their dormitory room doors. Credit Fox News Live for this deplorably dumb idea. If we let students change their locks, residential life and campus law enforcement will not be able to key into student rooms when they overdose on alcohol or try to commit suicide. This idea would prevent us from saving lives, rather than help to protect members of our community. The Virginia Tech killer could have shot through a lock, no matter whether it was the original or a retrofit. This is our property, and we need to have access to it. We need to focus our attention on the real issue: mental health.7

Perhaps the most preposterous suggestion of all is that we need to relax our campus weapons bans so that armed members of our communities can defend themselves. We should not allow weapons on college campuses. Imagine you are seated in Norris Hall, facing the whiteboard at the front of the room. The shooter enters from the back and begins shooting. What good is your gun going to do at this point? Many pro-gun advocates have talked about the deterrent and defense values of a well-armed student body, but none of them have mentioned the potential collateral criminal consequences of armed students: increases in armed robbery, muggings, escalation of interpersonal and relationship violence, etc. Virginia, like most states, cannot keep guns out of the hands of those with potentially lethal mental health crises. When we talk about arming students, we’d be arming them too. We need to focus our attention on the real issue: mental health.8

We should establish lockdown protocols that are specific to the nature of the threat. Lockdowns are an established mass-protection tactic. They can isolate perpetrators, insulate targets from threats, and restrict personal movement away from a dangerous line-of-fire. But, if lockdowns are just a random response, they have the potential to lock students in with a still-unidentified perpetrator. If not used correctly, they have the potential to lock students into facilities from which they need immediate egress for safety reasons. And, if not enforced when imposed, lockdowns expose us to the potential liability of not following our own policies. We should also establish protocols for judicious use of evacuations. When police at Virginia Tech herded students out of buildings and across the Drill Field, it was based on their assessment of a low risk that someone was going to open fire on students as they fled out into the open, and a high risk of leaving the occupants of certain buildings in situ, making evacuation from a zone of danger an appropriate escape method.9

We should not exclude from admission or expel students with mental health conditions, unless they pose a substantial threat of harm to themselves or others. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act prohibits colleges and universities from discrimination in admission against those with disabilities. It also prohibits colleges and universities from suspending or expelling disabled students, including those who are suicidal, unless the student is deemed to be a direct threat of substantial harm in an objective process based on the most current medical assessment available. Many colleges do provide health surveys to incoming students, and when those surveys disclose mental health conditions, we need to consider what appropriate follow-up should occur as a result. The Virginia Tech shooter was schizophrenic or mildly autistic, and identify-ing those disabilities early on and providing support, accommodation—and potentially intervention—is our issue.10

We should consider means and mechanisms for early intervention with students who exhibit behavioral issues, but we should not profile loners. At the University of South Carolina, the Behavioral Intervention Team makes many early catches of students whose behavior is threatening, disruptive, or potentially self-injurious. By working with faculty and staff at opening communication and support, the model is enhancing campus safety in a way that many other campuses are not. In the aftermath of what happened at Virginia Tech, I hope many campuses are considering a model designed to help raise flags for early screening and intervention. Many students are loners, isolated, withdrawn, pierced, tattooed, dyed, Wiccan, skate rats, fantasy gamers, or otherwise outside the “mainstream.” This variety enlivens the richness of college campuses, and offers layers of culture that quilt the fabric of diverse communities. Their preferences and differences cannot and should not be cause for fearing them or suspecting them. But, when any member of the community starts a downward spiral along the continuum of violence, begins to lose contact with reality, goes off their medication regimen, threatens, disrupts, or otherwise gains our attention with unhealthy or dangerous patterns, we can’t be bystanders any longer. Our willingness to intervene can make all the difference.11

All of the pundits insist that random violence can’t be predicted, but many randomly violent people exhibit a pattern of detectable disintegration of self, often linked to suicide. People around them perceive it. We can all be better attuned to those patterns and our protocols for communicating our concerns to those who have the ability to address them. This will focus our attention on the real issue: mental health.12

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

- Why does Sokolow begin his essay by discussing what “pundits and talking heads” think should be done to stop campus violence? Is this an effective opening strategy?

- In paragraph 2, Sokolow says, “Here’s what I think. These are just my opinions.” Do these two statements undercut or enhance his credibility? Why do you suppose he includes them?

- How does Sokolow propose to make campuses safer? Do you agree with his suggestions? Why or why not?

- Is Sokolow’s argument a refutation? If so, what arguments is he refuting?

- In what sense is this essay an ethical argument?

- In his concluding statement, Sokolow says that the real issue is “mental health.” What does he mean? Do you agree?

This essay is from the April 18, 2008, issue of the Chronicle of Higher Education.

JESUS M. VILLAHERMOSA JR.

GUNS DON’T BELONG IN THE HANDS OF ADMINISTRATORS, PROFESSORS, OR STUDENTS

In the wake of the shootings at Virginia Tech and Northern Illinois University, a number of state legislatures are considering bills that would allow people to carry concealed weapons on college campuses. I recently spoke at a conference on higher-education law, sponsored by Stetson University and the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators, at which campus officials discussed the need to exempt colleges from laws that let private citizens carry firearms and to protect such exemptions where they exist. I agree that allowing guns on campuses will create problems, not solve them.1

I have been a deputy sheriff for more than 26 years and was the first certified master defensive-tactics instructor for law-enforcement personnel in the state of Washington. In addition, I have been a firearms instructor and for several decades have served on my county sheriff ’s SWAT team, where I am now point man on the entry team. Given my extensive experience dealing with violence in the workplace and at schools and colleges, I do not think professors and administrators, let alone students, should carry guns.2

Some faculty and staff members may be capable of learning to be good shots in stressful situations, but most of them probably wouldn’t practice their firearms skills enough to become confident during an actual shooting. Unless they practiced those skills constantly, there would be a high risk that when a shooting situation actually occurred, they would miss the assailant. That would leave great potential for a bullet to strike a student or another innocent bystander. Such professors and administrators could be imprisoned for manslaughter for recklessly endangering the lives of others during a crisis.3

Although some of the legislative bills have been defeated, they may be reintroduced, or other states may introduce similar measures. Thus, colleges should at least contemplate the possibility of having armed faculty and staff members on their campuses, and ask themselves the following questions:4

Is our institution prepared to assume the liability that accompanies the lethal threat of carrying or using weapons? Are we financially able and willing to drastically increase our liability-insurance premium to cover all of the legal ramifications involved with allowing faculty and staff members to carry firearms?

How much time will each faculty and staff member be given each year to spend on a firing range to practice shooting skills? Will we pay them for that time?

Will their training include exposing them to a great amount of stress in order to simulate a real-life shooting situation, like the training that police officers go through?

Will the firearm that each one carries be on his or her person during the day? If so, will faculty and staff members be given extensive defensive-tactics training, so that they can retain their firearm if someone tries to disarm them?

The fact that a college allows people to have firearms could be publicized, and, under public-disclosure laws, the institution could be required to notify the general public which faculty or staff members are carrying them. Will those individuals accept the risk of being targeted by a violent student or adult who wants to neutralize the threat and possibly obtain their weapons?

If the firearms are not carried by faculty and staff members every day, where and how will those weapons be secured, so that they do not fall into the wrong hands?

If the firearms are locked up, how will faculty and staff members gain access to them in time to be effective if a shooting actually occurs?

Will faculty and staff members who carry firearms be required to be in excellent physical shape, and stay that way, in case they need to fight someone for their gun?

Will weapons-carrying faculty and staff members accept that they may be shot by law-enforcement officers who mistake them for the shooter? (All the responding officers see is a person with a gun. If you are even close to matching the suspect’s description, the risk is high that they may shoot you.)

“Will faculty and staff members be prepared to kill another person?”

Will faculty and staff members be prepared to kill another person, someone who may be as young as a teenager?

Will faculty and staff members be prepared for the possibility that they may miss their target (which has occurred even in police shootings) and wound or kill an innocent bystander?

Will faculty and staff members be ready to face imprisonment for manslaughter, depending on their states’ criminal statutes, if one of their bullets does, in fact, strike an innocent person?

Even if not criminally charged, would such faculty and staff members be prepared to be the focus of a civil lawsuit, both as a professional working for the institution and as an individual, thereby exposing their personal assets?

If any of us in the law-enforcement field were asked these questions, we could answer them all with absolute confidence. We have made a commitment to train relentlessly and to die, if we have to, in order to protect others. Experienced officers have typically fired tens of thousands of rounds practicing for the time when they might need those skills to save themselves or someone else during a lethal situation. We take that commitment seriously. Before legislators and college leaders make the decision to put a gun in the hands of a professor or administrator, they should be certain they take it seriously, too.5

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

- What is Villahermosa’s thesis? Where does he state it?

- What is Villahermosa trying to establish in paragraph 2? Do you think this paragraph is necessary?

- In the bulleted list in paragraph 4, Villahermosa poses a series of questions. What does he want this list to accomplish? Is he successful?

- What arguments does Villahermosa include to support his thesis? Which of these arguments do you find most convincing? Why?

- Do you think Villahermosa is making an ethical argument here? If so, on what ethical principle does he base his argument?

- What points does Villahermosa emphasize in his conclusion? Should he have emphasized any other points? Explain.

- Both Villahermosa and Timothy Wheeler (p. 616) deal with the same issue—guns on campus. Which writer do you think makes the stronger case? Why?

This article is from the October 11, 2007, issue of National Review.

TIMOTHY WHEELER

THERE’S A REASON THEY CHOOSE SCHOOLS

Wednesday’s shooting at yet another school has a better outcome than most in recent memory. No one died at Cleveland’s Success Tech Academy except the perpetrator. The two students and two teachers he shot are in stable condition at Cleveland hospitals.1

What is depressingly similar to the mass murders at Virginia Tech and Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania, and too many others was the killer’s choice of venue—that steadfastly gun-free zone, the school campus. Although murderer Seung-Hui Cho at Virginia Tech and Asa Coon, the Cleveland shooter, were both students reported to have school-related grudges, other school killers have proved to be simply taking advantage of the lack of effective security at schools. The Bailey, Colorado, multiple rapes and murder of September 2006, the Nickel Mines massacre of October 2006, and Buford Furrow’s murderous August 1999 invasion of a Los Angeles Jewish day-care center were all committed by adults. They had no connection to the schools other than being drawn to the soft target a school offers such psychopaths.2

This latest shooting comes only a few weeks after the American Medical Association released a theme issue of its journal Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. This issue is dedicated to analyzing the April 2007 Virginia Tech shootings, in which 32 people were murdered. The authors are university officials, trauma surgeons, and legal analysts who pore over the details of the incident, looking for “warning signs” and “risk factors” for violence. They rehash all the tired rhetoric of bureaucrats and public-health wonks, including the public-health mantra of the 1990s that guns are the root cause of violence.3

Sheldon Greenberg, a dean at Johns Hopkins, offers this gem: “Reinforce a ‘no weapons’ policy and, when violated, enforce it quickly, to include expulsion. Parents should be made aware of the policy. Officials should dispel the politically driven notion that armed students could eliminate an active shooter” (emphasis added). Greenberg apparently isn’t aware that at the Appalachian School of Law in 2002 another homicidal Virginia student was stopped from shooting more of his classmates when another student held him at gunpoint. The Pearl High School murderer Luke Woodham was stopped cold when vice principal Joel Myrick got his Colt .45 handgun out of his truck and pointed it at the young killer.4

Virginia Tech’s 2005 no-guns-on-campus policy was an abject failure at deterring Cho Seung-Hui. Greenberg’s audacity in ignoring the obvious is typical of arrogant school officials. What the AMA journal authors studiously avoid are on one hand the repeated failures of such feel-good steps as no-gun policies, and on the other hand the demonstrated success of armed first responders. These responders would be the students themselves, such as the trained and licensed law student, or their similarly qualified teachers.5

“Virginia Tech’s … no-guns-on-campus policy was an abject failure.”

In Cleveland this week and at Virginia Tech the shooters took time to walk the halls, searching out victims in several rooms, and then shooting them. Virginia Chief Medical Examiner Marcella Fierro describes the locations of the dead in Virginia Tech’s Norris Hall. Dead victims were found in groups ranging from 1 to 13, scattered throughout 4 rooms and a stairwell. If any one of the victims had, like the Appalachian School of Law student, used armed force to stop Cho, lives could have been saved.6

The people of Virginia actually had a chance to implement such a plan last year. House Bill 1572 was introduced in the legislature to extend the state’s concealed-carry provisions to college campuses. But the bill died in committee, opposed by the usual naysayers, including the Virginia Association of Chiefs of Police and the university itself. Virginia Tech spokesman Larry Hincker was quoted in the Roanoke Times as saying, “I’m sure the university community is appreciative of the General Assembly’s actions because this will help parents, students, faculty, and visitors feel safe on our campus.”7

It is encouraging that college students themselves have a much better grasp on reality than their politically correct elders. During the week of October 22–26 Students for Concealed Carry on Campus will stage a nationwide “empty holster” demonstration (peaceful, of course) in support of their cause.8

School officials typically base violence-prevention policies on irrational fears more than real-world analysis of what works. But which is more horrible, the massacre that timid bureaucrats fear might happen when a few good guys (and gals) carry guns on campus, or the one that actually did happen despite Virginia Tech’s progressive violence-prevention policy? Can there really be any more debate?9

AMA journal editor James J. James, M.D., offers up this nostrum:10

We must meaningfully embrace all of the varied disciplines contributing to preparedness and response and be more willing to be guided and informed by the full spectrum of research methodologies, including not only the rigid application of the traditional scientific method and epidemiological and social science applications but also the incorporation of observational/empirical findings, as necessary, in the absence of more objective data.

Got that?

I prefer the remedy prescribed by self-defense guru Massad Ayoob. When good people find themselves in what he calls “the dark place,” confronted by the imminent terror of a gun-wielding homicidal maniac, the picture becomes clear. Policies won’t help. Another federal gun law won’t help. The only solution is a prepared and brave defender with the proper lifesaving tool—a gun.11

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

- According to Wheeler, what is “depressingly similar” about the mass murders committed on campuses (para. 2)?

- What is Wheeler’s attitude toward those who said that “guns are the root cause of violence” (3)? How can you tell?

- Why, according to Wheeler, do college administrators and bureaucrats continue to ignore the answer to the problem of violence on campus? How does he refute their objections?

- Do you find Wheeler’s argument in support of his thesis convincing? What, if anything, do you think he could have added to strengthen his argument?

- How does Wheeler’s language reveal his attitude toward his subject? (For example, consider his use of “gem” in paragraph 4 and “politically correct” in paragraph 8.) Can you give other examples of language that conveys his point of view?

- How would you characterize Wheeler’s opinion of guns? How is his opinion different from Villahermosa’s (p. 613)?

- How do you think Wheeler would respond to the ideas in “Warning Signs: How You Can Help Prevent Campus Violence” (p. 629)? Which suggestions do you think he would support? Which would he be likely to oppose? Explain.

This opinion piece was published in the New York Times on February 27, 2014.

GREG HAMPIKIAN

WHEN MAY I SHOOT A STUDENT?

Boise, Idaho—To the chief counsel of the Idaho State Legislature:1

In light of the bill permitting guns on our state’s college and university campuses, which is likely to be approved by the state House of Representatives in the coming days, I have a matter of practical concern that I hope you can help with: When may I shoot a student?2

I am a biology professor, not a lawyer, and I had never considered bringing a gun to work until now. But since many of my students are likely to be armed, I thought it would be a good idea to even the playing field.3

I have had encounters with disgruntled students over the years, some of whom seemed quite upset, but I always assumed that when they reached into their backpacks they were going for a pencil. Since I carry a pen to lecture, I did not feel outgunned; and because there are no working sharpeners in the lecture hall, the most they could get off is a single point. But now that we’ll all be packing heat, I would like legal instruction in the rules of classroom engagement.4

At present, the harshest penalty available here at Boise State is expulsion, used only for the most heinous crimes, like cheating on Scantron exams. But now that lethal force is an option, I need to know which infractions may be treated as de facto capital crimes.5

I assume that if a student shoots first, I am allowed to empty my clip; but given the velocity of firearms, and my aging reflexes, I’d like to be proactive. For example, if I am working out a long equation on the board and several students try to correct me using their laser sights, am I allowed to fire a warning shot?6

If two armed students are arguing over who should be served next at the coffee bar and I sense escalating hostility, should I aim for the legs and remind them of the campus Shared-Values Statement (which reads, in part, “Boise State strives to provide a culture of civility and success where all feel safe and free from discrimination, harassment, threats or intimidation”)?7

While our city police chief has expressed grave concerns about allowing guns on campus, I would point out that he already has one. I’m glad that you were not intimidated by him, and did not allow him to speak at the public hearing on the bill (though I really enjoyed the 40 minutes you gave to the National Rifle Association spokesman).8

Knee-jerk reactions from law enforcement officials and university presidents are best set aside. Ignore, for example, the lame argument that some drunken frat boys will fire their weapons in violation of best practices. This view is based on stereotypical depictions of drunken frat boys, a group whose dignity no one seems willing to defend.9

“I would point out that urinating against a building or firing a few rounds into a sorority house are both violations of the same honor code.”

The problem, of course, is not that drunken frat boys will be armed; it is that they are drunken frat boys. Arming them is clearly not the issue. They would cause damage with or without guns. I would point out that urinating against a building or firing a few rounds into a sorority house are both violations of the same honor code.10

In terms of the campus murder rate—zero at present—I think that we can all agree that guns don’t kill people, people with guns do. Which is why encouraging guns on campus makes so much sense. Bad guys go where there are no guns, so by adding guns to campus more bad guys will spend their year abroad in London. Britain has incredibly restrictive laws—their cops don’t even have guns!—and gun deaths there are a tiny fraction of what they are in America. It’s a perfect place for bad guys.11

Some of my colleagues are concerned that you are encouraging firearms within a densely packed concentration of young people who are away from home for the first time, and are coincidentally the age associated with alcohol and drug experimentation, and the commission of felonies.12

Once again, this reflects outdated thinking about students. My current students have grown up learning responsible weapon use through virtual training available on the Xbox and PlayStation. Far from being enamored of violence, many studies have shown, they are numb to it. These creative young minds will certainly be stimulated by access to more technology at the university, items like autoloaders, silencers, and hollow points. I am sure that it has not escaped your attention that the library would make an excellent shooting range, and the bookstore could do with fewer books and more ammo choices.13

I want to applaud the Legislature’s courage. On a final note: I hope its members will consider my amendment for bulletproof office windows and faculty body armor in Boise State blue and orange.14

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

- This essay is written as a letter addressed to the chief counsel of the Idaho State legislature. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this format?

- What is the context for Hampikian’s argument? For example, what situation gave rise to the letter? What issue is Hampikian considering? How contentious is the debate concerning this issue?

- Satire is the use of humor, irony, or exaggeration to ridicule a person, doctrine, or institution. In what sense is this essay satire?

- In paragraph 10, Hampikian says, “The problem, of course, is not that drunken frat boys will be armed; it is that they are drunken frat boys.” What does he mean?

- Hampikian purposely strings together a number of fallacies in paragraph 11 to underscore the weakness of the arguments against his position. How effective is this strategy? Would a more direct approach—simply addressing opposing arguments one by one—have been more effective? Explain.

- Hampikian concludes his essay on a humorous note. What serious point is he making? Is humor appropriate here? Why or why not?

- How would you define Hampikian’s tone? Is it humorous? Respectful? Condescending? Sarcastic? Something else? How does Hampikian’s tone affect your response to his essay?

The Washington Post published this article on October 27, 2014.

TODD C. FRANKEL

CAN WE INVENT OUR WAY OUT OF SCHOOL VIOLENCE?

The idea came to her in the vulnerable early morning hours, just after the horrific shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut, nearly two years ago.1

Celisa Edwards, a teacher, was shaken. What if a gunman burst into her school in this small town outside Atlanta? She could follow lockdown procedures. Turn off the lights. Lock the door. But that didn’t seem like enough to protect her seventh graders. Edwards had an idea. She hastily sketched it out and, a couple of hours later, woke up her husband. We need to make this, she told him.2

The result was a simple metal wire with looped ends that could secure classroom doors from the inside. The Portable Affordable Lockdown System, patent pending, has been installed in one Georgia school. Edwards recently pitched it to another district.3

Now, Edwards—whose only previous inventions involved devising lesson plans—was discussing her device with evangelical fervor during a free period late last week at Dacula Middle School. About the same time, hundreds of miles away in Maryville, Washington, a high school was going on lockdown after a student fatally shot two people and injured four others (one of whom later died). Almost immediately, the question, “What could’ve been done to prevent this?” was in the air.4

“Our classrooms are not safe. There are people bent on doing wrong, doing evil,” Edwards says. “And we are deterring those perpetrators.”5

A flood of school-safety inventions have hit the market in recent years, many of them created by novices stunned by what happened at Sandy Hook, where a gunman fatally shot 20 young students and six staff members in 2012. Since then, teachers and parents have come up with a range of door barricades, bulletproof backpacks, ballistic whiteboards, and online apps to monitor for homicidal plots. These products join a school security market that is expected to reach $720 million this year, according to research firm IHS. And the dozens of school shootings that have occurred since Sandy Hook only ramp up the hunt for a solution.6

Although they could be dismissed as profiting from tragedy, inventors such as Edwards say they are motivated by fear and a sense that policymakers have failed to safeguard students and teachers.7

Kenneth Trump, a national school safety consultant, understands the attraction of the inventions. People felt helpless after Sandy Hook, he said. And there was a major push to “do something.” But the national debate over how to prevent school shootings soon stalled out, grounded mostly by ideological divisions over gun control. And into that gaping void went these inventions, many of them focused on hardening a school’s defenses. But Trump said he doubts that door locks and bulletproof materials would make a difference.8

“What’s really being sold here is an emotional security blanket,” he said.9

But that hasn’t slowed the sales of ballistic whiteboards, made by a company in Pocomoke City, Maryland, that crafts anti-IED armor for the U.S. military. The small, handheld whiteboards can act as defensive shields to fend off a gunman. George Tunis, chief executive of Hardwire, said the Sandy Hook shooting convinced him that his company had a role in protecting schools.10

“That’s when it hit us, that these are fast events, and the armor needs to be in schools,” Tunis said.11

Hardwire’s whiteboards, which sell for $399, are in nearly 1,000 schools in 50 states, he said. Later this week, the Colonial School District in New Castle, Delaware, will introduce its 121 whiteboards for use in classrooms.12

In Jefferson Hills, Pennsylvania, a school maintenance man invented an emergency door lock after the Sandy Hook shooting. Students at Banneker High School in Washington, D.C., won a grant to develop a sleeve that jams a door’s hydraulic closer. A group of teachers in Muscatine, Iowa, formed Fighting Chance Solutions to sell something similar. A company in Burlington, Vermont, released its Social Sentinel app to scour social media for signs of a school threat. And a father in Williamston, Michigan, created The Boot, a steel bar that blockades a classroom door.13

Robert Couturier had been kicking around that idea a few years before Sandy Hook happened. He started a company, which now has 14 full-time employees. Last week, he hired two more salesmen. He invented The Boot because he was tired of hearing about school shootings.14

“I had to come up with a solution,” Couturier said.15

Since the Sandy Hook shooting, much of the discussion has been about whether to arm teachers. Many states introduced bills to allow guns in schools, but only a handful enacted laws specifically allowing firearms in public schools. One of them was Georgia, which earlier this year began allowing licensed gun owners to carry weapons inside bars, nightclubs, and schools.16

Trump, who has worked as a school safety consultant for three decades, noted how different the response was following the 1999 Columbine High School shooting in Colorado, where 12 students and one teacher were killed. Back then, the discussion focused on training school officials to spot warning signs and offering mental health support services. But these initiatives take longer to roll out and require sustained investment, he said. The emotional intensity of the Sandy Hook shooting seemed to demand a quicker fix.17

“The emotional intensity of the Sandy Hook shooting seemed to demand a quicker fix.”

“People are frustrated that there have been so many steps taken and they still have this happen,” Trump said.18

Back at Dacula Middle School, Edwards was demonstrating her invention. Her seventh graders had just filed out of the room, walking past a ball python curled up in a glass enclosure by the door, after their discussion of the Theodore Taylor book The Cay. Edwards, 48, had energetically read aloud passages.19

Now, she used that same intensity to show off her device. The wire rope was about two feet long and encased in plastic. Each end was looped, with a carabiner at one end. A metal eye hook had been drilled into a concrete-block wall, near a hand-crank pencil sharpener.20

Edwards quickly hooked one end around the door handle and latched the other to the eye hook. The door was secure. No one was getting in or out. The door handle had a lock, but Edwards pointed out that administrators had keys that a gunman could take. Her simple invention had solved that problem.21

“Teachers find solutions to problems. And my passion is for classroom safety,” she said. “That’s why I designed this.”22

After her demonstration, Edwards slipped the device back into a small green bag and returned it to its familiar spot in her desk drawer, so she’d know exactly where it was, if she ever needed it.23

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

- Frankel begins and ends his essay by discussing Celisa Edwards, a teacher who invented a device to secure a classroom door. Why does he do this? What are the advantages of this strategy?

- Although this essay does not have a stated thesis, it does make a point. On the lines below, write a one-sentence thesis statement for this essay.

Although inventors have come up with products to stop school shootings, _____________________________

__________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________.

- In his essay, Frankel describes several inventions that are supposed to promote school safety. What is his opinion of these inventions? How can you tell?

- What does Kenneth Trump mean when he says, “What’s really being sold here is an emotional security blanket” (para. 9)?

- According to Kenneth Trump, people responded differently to the Columbine High School shooting and to the shooting that took place at Sandy Hook Elementary School. Why? (Before you answer, read some background information about these shootings.)

- In what sense, if any, could this essay be considered an argument?

This piece ran on February 18, 2015, in the New York Times.

ALAN SCHWARZ

A BID FOR GUNS ON CAMPUSES TO DETER RAPE

As gun rights advocates push to legalize firearms on college campuses, an argument is taking shape: Arming female students will help reduce sexual assaults.1

Support for so-called campus carry laws had been hard to muster despite efforts by proponents to argue that armed students and faculty members could prevent mass shootings like the one at Virginia Tech in 2007. The carrying of concealed firearms on college campuses is banned in 41 states by law or by university policy. Carrying guns openly is generally not permitted.2

But this year, lawmakers in 10 states who are pushing bills that would permit the carrying of firearms on campus are hoping that the national spotlight on sexual assault will help them win passage of their measures.3

“If you’ve got a person that’s raped because you wouldn’t let them carry a firearm to defend themselves, I think you’re responsible,” State Representative Dennis K. Baxley of Florida said during debate in a House subcommittee last month. The bill passed.4

The sponsor of a bill in Nevada, Assemblywoman Michele Fiore, said in a telephone interview: “If these young, hot little girls on campus have a firearm, I wonder how many men will want to assault them. The sexual assaults that are occurring would go down once these sexual predators get a bullet in their head.”5

In addition to those in Florida and Nevada, bills that would allow guns on campus have been introduced in Indiana, Montana, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Wyoming.6

Opponents contend that university campuses should remain havens from the gun-related risks that exist elsewhere, and that college students, with high rates of binge drinking and other recklessness, would be particularly prone to gun accidents.7

“Opponents contend that university campuses should remain havens.”

Some experts in sexual assault said that college women were typically assaulted by someone they knew, sometimes a friend, so even if they had access to their gun, they would rarely be tempted to use it.8

“It reflects a misunderstanding of sexual assaults in general,” said John D. Foubert, an Oklahoma State University professor and national president of One in Four, which provides educational programs on sexual assault to college campuses. “If you have a rape situation, usually it starts with some sort of consensual behavior, and by the time it switches to nonconsensual, it would be nearly impossible to run for a gun. Maybe if it’s someone who raped you before and is coming back, it theoretically could help them feel more secure.”9

Other objectors to the bills say that advocates of the campus carry laws, predominantly Republicans with well-established pro-gun stances, are merely exploiting a hot-button issue.10

“The gun lobby has seized on this tactic, this subject of sexual assault,” said Andy Pelosi, the executive director of the Campaign to Keep Guns Off Campus. “It resonates with lawmakers.”11

Colorado, Wisconsin, and seven other states allow people with legal carry permits to take concealed firearms to campus, some with restrictions. (For example, Michigan does not allow guns in dormitories or classrooms.) Many of those states once had bans but lifted them in recent legislative cycles, suggesting some momentum for efforts in 2015.12

Past debates in Colorado, Michigan, and Nevada have included testimony in support of campus carry laws from Amanda Collins, who in 2007 was raped on the campus of the University of Nevada, Reno; Ms. Collins has said that had she been carrying her licensed gun, she would have averted the attack. It is unclear whether Ms. Collins will testify anywhere this year.13

Some surveys have estimated that a vast majority of college presidents and faculty members oppose allowing firearms on campus. Support was somewhat higher among students, but 67 percent of men and 86 percent of women still disliked the concept.14

Many students who support current legislation have joined the lobbying group Students for Concealed Carry. Crayle Vanest, an Indiana University senior who recently became the first woman on the group’s national board, said she should be able to carry her licensed .38-caliber Bersa Thunder pistol on campus, where she said she had walked unarmed after her late-night shifts at a library food court.15

“Universities are under a ton of investigation for how they handle sexual assaults — that shows how safe campus maybe isn’t,” said Ms. Vanest, who is lobbying Indiana lawmakers. “Our female membership has increased massively. People who weren’t listening before are listening now.”16

Some lawmakers said they expected that votes on the bills would largely be along party lines. Ms. Fiore of Nevada, for example, predicted the Republican-controlled Legislature and Republican governor would enact her bill. She added that people who understood the extent of sexual assaults on college campuses, perhaps female Democrats who had been sexually assaulted themselves, “need to call their legislators and say, ‘Represent us today or lose your election tomorrow.’”17

A South Carolina state senator, Brad Hutto, a Democrat who will oppose a campus carry bill when it is considered by the judiciary committee, said he doubted that sexual assault would swing his state’s debate but, “I know that that’s a card that’s going to be used.”18

The most interesting debate could occur in Florida, where several story lines intersect. Florida State University has had high-profile episodes involving sexual assault—the star football player Jameis Winston was accused of raping a fellow student in 2012 but did not face criminal charges—as well as a shooting in November in which a 31-year-old gunman opened fire at a campus library, wounding two students and an employee before being fatally shot by the police.19

The university’s president, John Thrasher, is a former state senator, former chairman of the state’s Republican Party, and a vocal gun rights supporter. But he opposes guns on university grounds, in part because of a 2011 death: Ashley Cowie, a sophomore and the daughter of one of Mr. Thrasher’s close friends, was shot and killed when another student, showing off his rifle in a fraternity house, did not realize the weapon was loaded.20

“A college campus is not a place to be carrying guns around; our campus police agree with that, and so does law enforcement,” Mr. Thrasher said.21

Mariana Prado, a sophomore at Stetson University in DeLand, Florida, said: “I think it’s a terrible idea. From what I’ve seen, sexual assault is often linked to situations where people are drinking, so it’s not a good idea to have concealed weapons around that.”22

The next stop for the Florida bill will be a committee hearing in March. Greg Steube, the original sponsor of the bill, said he hoped that inviting Ms. Collins, the former Nevada student who was raped in 2007, to testify would help it reach the desk of Gov. Rick Scott, a Republican, and become law.23

“It’s moving to hear from a young woman that had a concealed carry and but for a university policy, she was raped,” Mr. Steube said. “I don’t know if it can get any more compelling than that.”24

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

- Schwarz begins his essay by observing that “an argument is taking shape” (para. 1). To what is he referring? Is this point self-evident, or does Schwarz need to supply proof or explanation?

- List other points that Schwarz presents as self-evident. Next to each point, note the evidence that he could provide to support it.

- Schwarz alludes to “opponents” (7), “some experts” (8), “other objectors” (10), and “some surveys” (14). Should he have identified the individuals to whom he refers? Why or why not?

- In paragraph 5, Schwarz quotes Assemblywoman Michele Fiore, the sponsor of a bill to allow students to carry concealed firearms, who says, “If these young, hot little girls on campus have a firearm, I wonder how many men will want to assault them”? Do you think Fiore’s statement helps or hurts her case? Explain.

- What is Schwarz’s purpose in writing this essay? To inform? To persuade? To entertain? Something else? How can you tell?

- In his conclusion, Schwarz refers to Amanda Collins, a student who says that had she been able to carry her licensed gun on the campus of the University of Nevada, she would not have been raped. Does this conclusion support Schwarz’s thesis? Why or why not? What is another concluding strategy Schwarz could have used?

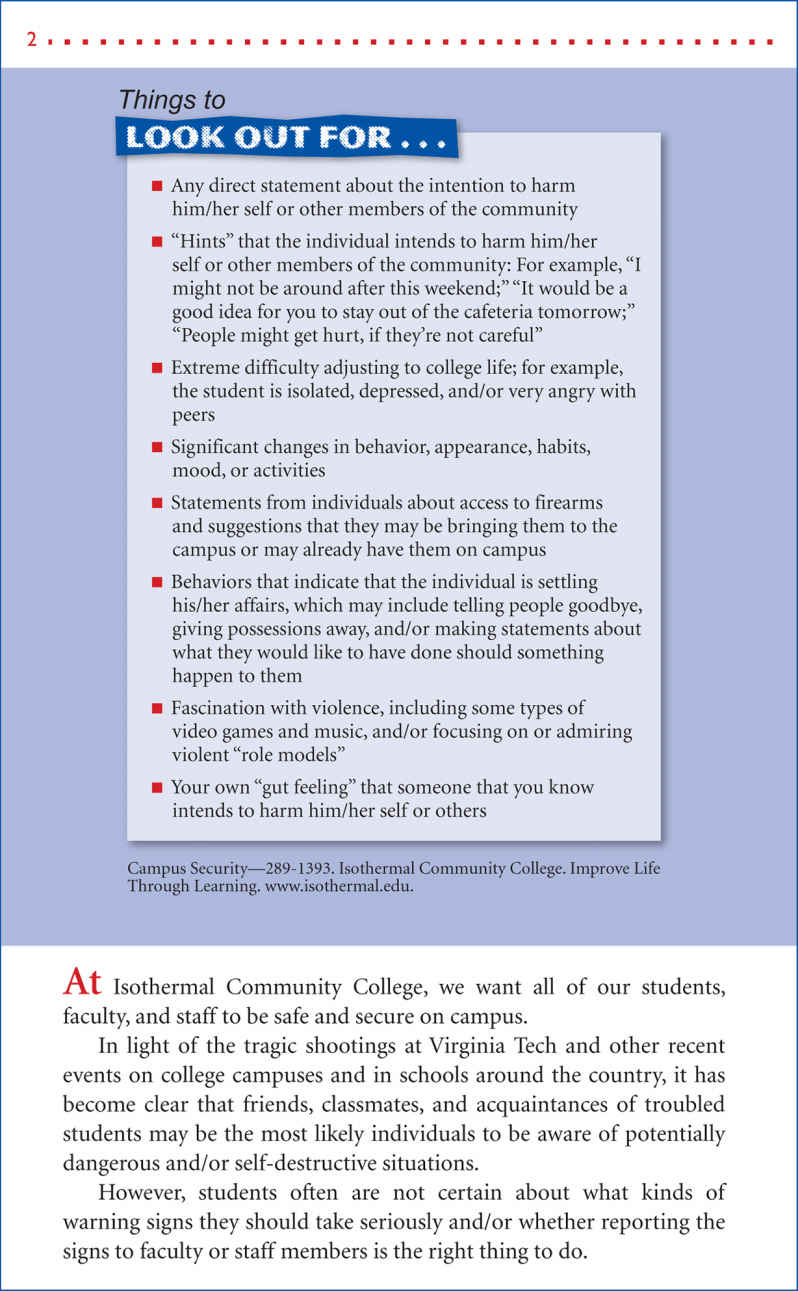

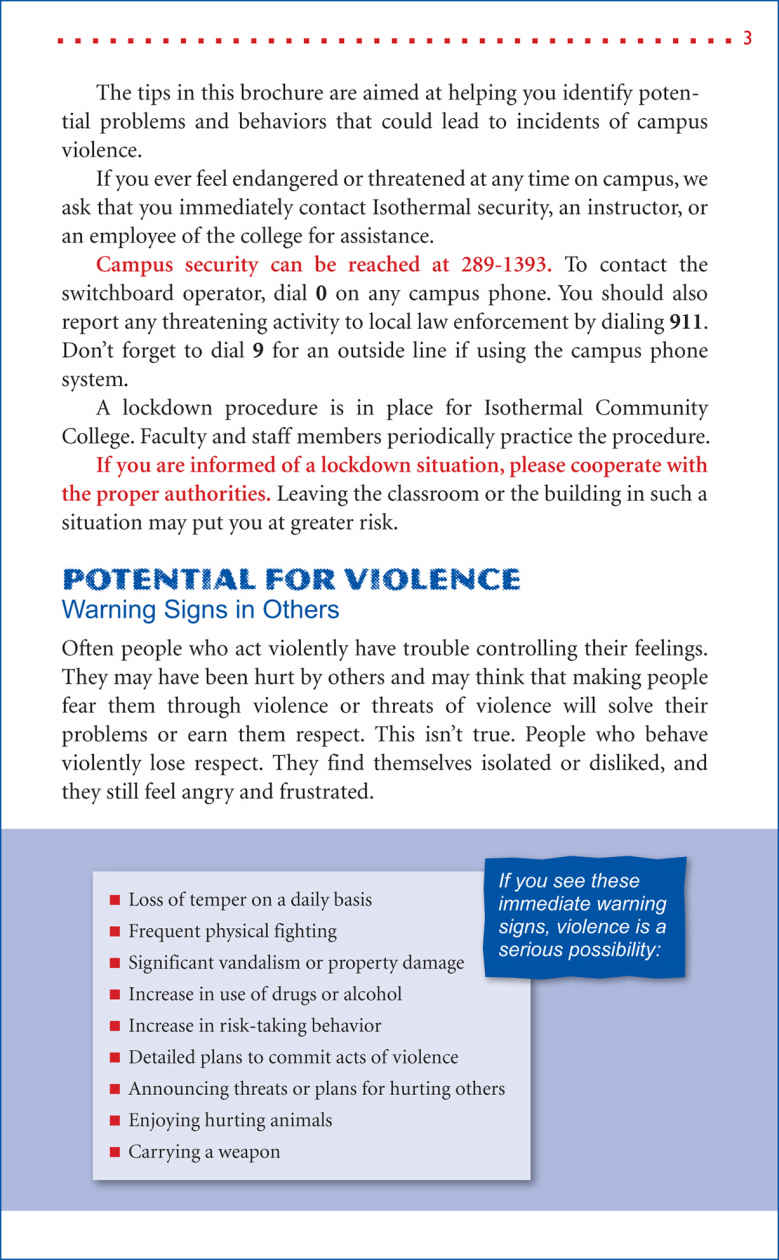

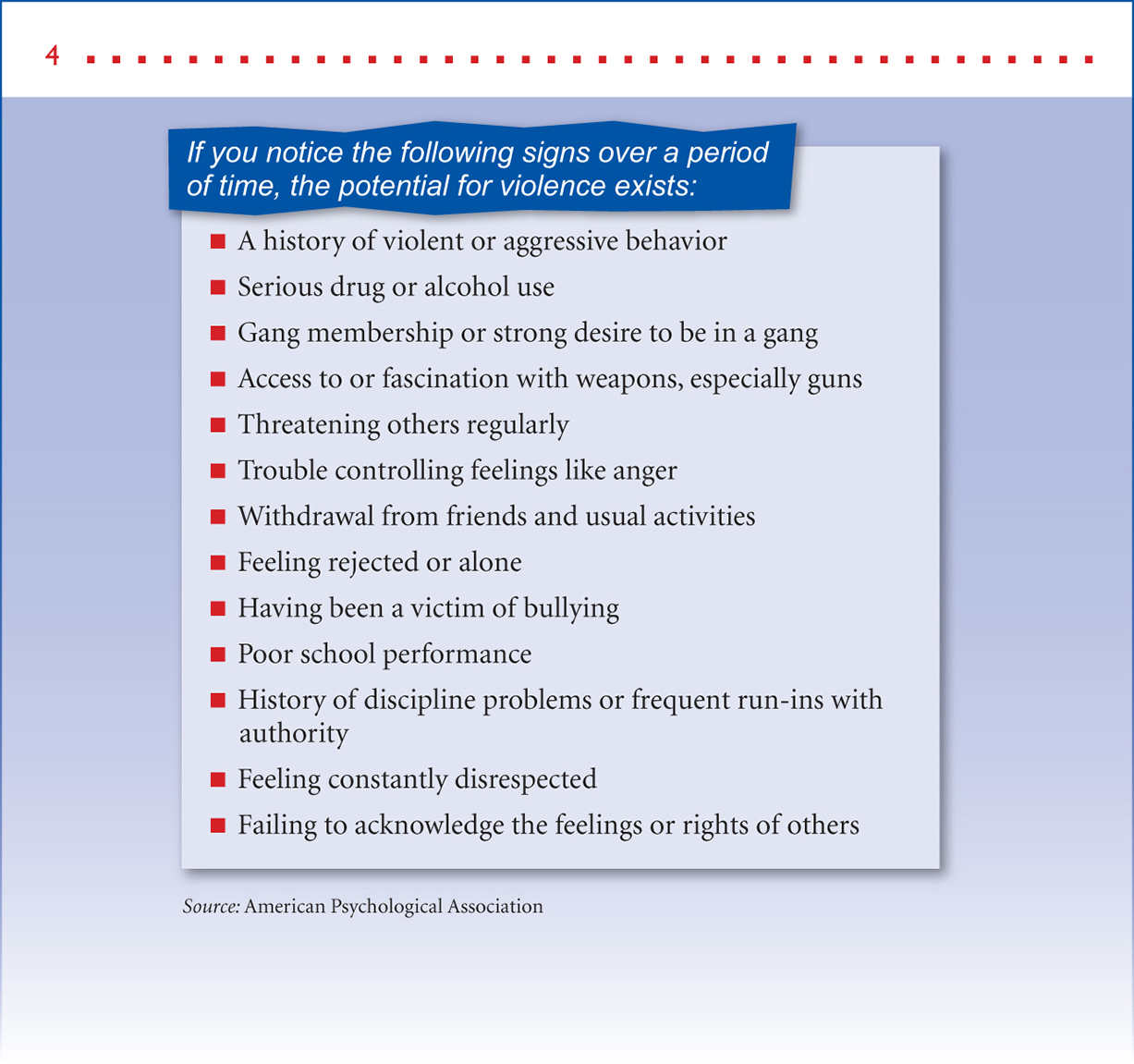

This brochure is available on the website for Isothermal Community College, isothermal.edu.

WARNING SIGNS: HOW YOU CAN HELP PREVENT CAMPUS VIOLENCE

Isothermal Community College

Isothermal Community College

Isothermal Community College

Isothermal Community College

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

- This brochure is designed to help students recognize people who have the potential to commit campus violence. What warning signs does the brochure emphasize?

- What additional information, if any, do you think should have been included in this brochure? Why?

- Are there any suggestions in this brochure that could possibly violate a person’s right to privacy? Explain.

- What additional steps do you think students should take to prevent campus violence?

This poster is from the UCDA Campus Violence Poster Project show at Northern Illinois University.

GONE BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

© Amy Dion, Art Director, SIU

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

- This poster shows a handprint on a background that repeats the phrase “Gone but not forgotten.” What ethical argument does the poster make?

- What other images does the poster include? How do these images reinforce its message?

- Do you think posters like this one can really help to combat campus violence? Can they serve any other purpose? Explain.

TEMPLATE FOR WRITING AN ETHICAL ARGUMENT

Write a one-paragraph ethical argument in which you answer the question, “How far should schools go to keep students safe?” Follow the template below, filling in the blanks to create your argument.

Recently, a number of schools have experienced violence on their campuses. For example,__________________________________________________. Many schools have gone too far (or not far enough) in trying to prevent violence because ___________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_________________________________________. One reason ____________________________________________________________. Another reason ________________________________

_________________________________________. Finally, ____________________________________________

________________________________________. If schools really want to remain safe, ______________________________________

_______________________________________________

____________________________________

_____________________________.

EXERCISE 16.7

EXERCISE 16.7

Ask your friends and your teachers whether they think any of the steps your school has taken to prevent campus violence are excessive—or whether they think these measures don’t go far enough. Then, revise the paragraph you wrote in the template on the previous page so that it includes their opinions.

EXERCISE 16.8

EXERCISE 16.8

Write an ethical argument in which you consider the topic, “How Far Should Schools Go to Keep Students Safe?” Make sure you include a clear analysis of the ethical principle that you are going to apply. (If you like, you may incorporate the material you developed in the template and in Exercise 16.7 into your essay.) Cite the readings on pages 609–634, document the sources you use, and be sure to include a works-cited page. (See Chapter 10 for information on documenting sources.)

EXERCISE 16.9

EXERCISE 16.9

Review the four pillars of argument discussed in Chapter 1. Does your essay include all four elements of an effective argument? Add anything that is missing. Then, label the key elements of your essay.

WRITING ASSIGNMENTS: ETHICAL ARGUMENTS

WRITING ASSIGNMENTS: ETHICAL ARGUMENTS

- Write an ethical argument in which you discuss whether hate groups have the right to distribute material on campus. Be sure to explain the ethical principle you are applying and to include several arguments in support of your position. (Don’t forget to define and give examples of what you mean by hate groups. Remember to address arguments against your position.) You can refer to the readings on pages 165–185 to find sources to support your position.

- Should English be made the official language of the United States? Write an ethical argument in which you take a position on this topic.

- Many people think that celebrities have an ethical obligation to set positive examples for young people. Assume that you are a celebrity, and write an op-ed piece in which you support or challenge this idea. Be sure to identify the ethical principle on which you base your argument.

Part 5 Review: Combining Argumentative Strategies

In Chapter 12–16, you have seen how argumentative essays can use different strategies to serve particular purposes. The discussions and examples in these chapters highlighted the use of a single strategy for a given essay. However, many (if not most) argumentative essays combine several different strategies.

For example, an argument recommending that the United States implement a national sales tax could be largely a proposal argument, but it could present a cause-and-effect argument to illustrate the likely benefits of the proposal, and it could also use an evaluation argument to demonstrate the relative advantages of this tax as compared to other kinds of taxes.

The following two essays—“Get the Lead out of Hunting” and “Fulfill George Washington’s Last Wish—a National University”—illustrate how various strategies can work together in a single argument. Note that both essays include the four pillars of argument—thesis statement evidence refutation and concluding statement. (The first essay includes marginal annotations that identify the different strategies the writer uses to advance his argument.)

This opinion essay is from the December 15, 2010, New York Times.

ANTHONY PRIETO

GET THE LEAD OUT OF HUNTING

I’ve hunted elk, deer, and wild pigs in the American West for 25 years. Like many hunters, I follow several rules: Respect other forms of life, take only what my family can eat and the ecosystem can sustain, and leave as little impact on the environment as possible.1

Cause-and-effect argument

Ethical argument

That’s why I hunt with copper bullets instead of lead. We’ve long known about the collateral damage caused by lead ammunition. When bald and golden eagles, vultures, bears, endangered California condors, and other scavengers eat the innards, called gutpiles, that hunters leave in the field after cleaning their catch or the game that hunters wound but don’t capture, they can ingest poisonous lead fragments. Most sicken, and many die.2

Cause-and-effect argument

When I began hunting, I buried the lead-laden gutpiles. It would help if more hunters did this, but it’s not enough. Scavengers often dig gutpiles up anyway. And the meat that hunters take home to their families could be tainted. I’ve seen X-rays of shot game showing dust-sized lead particles spread throughout the meat, far away from the bullet hole. The best solution is to stop using lead ammunition altogether.3

Proposal argument

So last summer conservationists—along with the organization I run—formally petitioned the Environmental Protection Agency to ban lead bullets and shot nationwide (there are limited bans for some hunting areas and game). The E.P.A. rejected the petition, and we’ve since filed a lawsuit to get the agency to address the problem.4

Unfortunately, there is vocal opposition to any ammunition regulation from groups like the National Rifle Association and the National Shooting Sports Foundation, which see the campaign as an attack on hunting rights and fear that the cost of non-lead ammunition would drive hunters away from the sport.5

But this campaign has nothing to do with revoking hunting rights; if it did, I would not be involved. It’s an issue of using non-toxic materials. Was the removal of lead paint from children’s toys a plot to do away with toys? Did the switch to unleaded gas hide an ulterior motive of removing vehicles from our roads?6

And although copper bullets can be more expensive than lead ones, the cost of ammunition is a small fraction of what I spend on hunting, which includes gear, optics, food, gas, and licenses. No one will quit hunting over spending a few more quarters per bullet. Besides, the more hunters switch to copper, the faster prices will come down. Back in the ’90s, before pre-loaded copper cartridges could be bought over the counter, I had to hand-load my copper bullets. But already it’s easy to find them in many calibers, including those for my Browning .270 and my Winchester .300.7

Evaluation argument

Evaluation argument

The dozen friends I hunt with love shooting non-lead bullets, and it’s not just because they’re doing something good for the environment. The ballistics are better. I’ve killed more than 80 pigs and 40 deer shooting copper. These bullets travel up to 3,200 feet per second and have about a 98 percent weight retention—meaning they don’t fragment as easily as lead. Copper kills cleanly. It can help keep our hunting grounds clean as well.8

“Copper kills cleanly.”

![]()

Review Exercise 1

- Prieto uses various argument strategies in “Get the Lead out of Hunting,” which are identified in the annotations. Why is each strategy used?

- How does each strategy support the argument the writer makes?

- Does one particular strategy seem to dominate the essay—that is, do you see it as largely a proposal argument, an ethical argument, or something else?

- Where, if anywhere, could Prieto have used a definition argument? What might this strategy have added to this essay?

This article first appeared on CNN.com on March 2, 2015.

KEVIN CAREY

Fulfill George Washington’s Last Wish—a National University

In 1796, in his final annual address to Congress, President George Washington called for the creation of:1

“… a National University; and also a Military Academy. The desirableness of both these Institutions, has so constantly increased with every new view I have taken of the subject, that I cannot omit the opportunity of once for all, recalling your attention to them.”2

The Military Academy was soon built at West Point. But despite leaving $22,222 for its establishment (a lot of money back then) in his last will and testament, Washington’s National University never came to pass.3

Instead, lawmakers chose to rely on state governments and religious denominations to build and finance new colleges and universities.4

Today, the American higher education system is in crisis. The price of college has grown astronomically, forcing students and parents to take out loans that now exceed $1.2 trillion in outstanding debt. Many of those loans are falling into default as graduates struggle to find work. The latest research suggests that our vaunted universities are producing graduates who haven’t learned very much.5

The time has come to revive George Washington’s great idea, in 21st century form. Advances in information technology that would have seemed like pure magic in colonial times mean we can now create a 21st Century National University that will help millions of students get a high-quality, low-cost college education—without hiring any professors, building any buildings, or costing the taxpayers a dime.6

Washington’s Role

To see how, it helps to understand the three ways the federal government currently supports higher education.7

Two of them are well known. First, the Defense Department, National Institutes of Health, and other federal agencies spend hundreds of billions of dollars financing university-based research, contributing to countless scientific breakthroughs and commercial innovations. Second, the U.S. Department of Education provides $150 billion annually in grants and loans to help students pay for college.8

“Second, the U.S. Department of Education provides $150 billion annually in grants and loans to help students pay for college.”

As tuitions rise and states continue to slash funding for public universities (Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker recently proposed $300 million in new cuts), the federal government has become the college financier of last resort.9

But there is a third essential federal role in higher education that is far less well known. In many ways, it’s the most important of them all, and the key to creating a 21st Century National University. In addition to funding colleges, the federal government approves colleges.10

It does this through a little-understood process called accreditation. To be eligible for those billions of research and financial aid dollars, colleges must be accredited. Technically, accreditors are nonprofit organizations run by consortia of existing colleges. But in order to make a college eligible for federal money, accreditors must first be approved by the federal government. Without that approval and the money that goes along with it, both colleges and accreditors would immediately close up shop. In other words, Uncle Sam ultimately decides who gets to be an American college and grant college degrees.11

A University with No Buildings

So, here’s the big idea: In order to build a 21st Century National University, all the federal government has to do is something very simple: Approve itself.12

In George Washington’s days, this would have been only the first step of a process subsequently involving the construction of an actual university. Doing this today would accomplish little in solving the higher education crisis, because physical universities cost billions of dollars to construct from scratch and can still only enroll a handful of the many students who can’t afford a good education.13

Fortunately, there’s no need for new buildings—or, for that matter, administrators, libraries, faculty, and all the rest. Existing colleges and universities, flush with federal dollars, have already created all the essential building blocks for National U. Anyone with an Internet connection can log on to Coursera, edX, saylor.org, and many other websites offering high-quality online courses, created by many of the world’s greatest universities and taught by tenured professors, for free.14

Tens of millions of students have already signed up for these courses over the last four years. Yet enrollment in traditional colleges hasn’t flagged, and prices have continued to rise. The reason is clear. The free college providers can’t (or won’t) give online students the one thing they need more than anything else: a college degree. Elite universities like Harvard and Stanford don’t want to dilute their exclusive brands. Nonelite universities don’t want to give away something they’re currently selling for a lot of money.15

That’s where the federal government comes in. With some authorizing language from Congress and a small, one-time start-up budget, the U.S. Department of Education could create a nonprofit, bipartisan organization with only two missions: approving courses and granting degrees.16

Don’t worry, federal bureaucrats won’t be in charge of academic matters. Instead, National U. would hire teams of leading scholars to evaluate and approve courses. Some of the decisions shouldn’t be difficult.17

For example, this week, edX is launching a free, nine-week-long online course called “Introduction to Computational Thinking and Data Science.” It will be taught by Dr. Eric Grimson, who is the chancellor of the renowned Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Dr. John Guttag, who leads the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory’s Data Driven Medical Research Group. The course materials mirror those taught to some of the smartest students in the world on MIT’s campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts.18

It seems likely that this is a good course.19

A Degree from National U.

National U., moreover, wouldn’t be limited to courses from existing colleges. Any higher education provider, public or private sector, could submit a course for approval. Those that aren’t already accredited would pay a fee to cover the cost of evaluation.20

National U. would also map out which courses students need to take to earn an associate or bachelor’s degree. This won’t be difficult, since existing colleges have already established a standard set of requirements: a certain number of approved lower- and upper-division courses, plus an approved sequence in an academic major, adding up to 60 or 120 credits. Once students complete the credits, National U. will grant them a degree.21

While many of the courses will be free, students will bear small costs for taking exams through secure online channels or in-person testing facilities. (Textbooks will be free and open-source.) Students will also pay a modest fee of a few hundred dollars for the degree itself, enough to defray the operating costs of National U.22

Lower-income students will be able to pay for those expenses using the same federal grant and loan programs they currently use to pay tuition at accredited colleges. Since National U. will likely be much cheaper, this will actually save the taxpayers money in the long run.23

If it all sounds too good to be true, keep in mind that free online courses from the likes of MIT are a very recent phenomenon. Higher education policies just haven’t adapted to them—yet.24

The federal government’s higher education approval powers are long-established. Now it just needs to use them on behalf of students, instead of traditional colleges and universities that are charging far too much. George Washington was right all along.25

![]() Review Exercise 2

Review Exercise 2

- What proposal argument does Carey make in this essay?

- Label the strategies used in this essay, following the model of the Prieto essay on page 638.

- Where does Carey make a cause-and-effect argument? What causes and effects does he identify?

- Where does Carey make an evaluation argument? What is he evaluating? On what criteria does he base his essay?