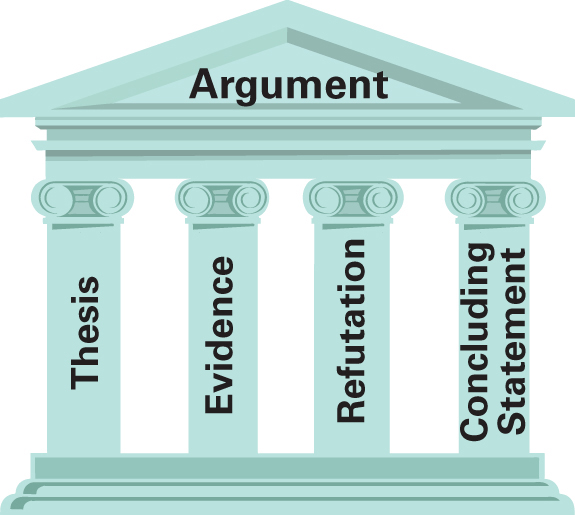

Structuring a Proposal Argument

In general, a proposal argument can be structured in the following way:

Introduction: Establishes the context of the proposal and presents the essay’s thesis

Explanation of the problem: Identifies the problem and explains why it needs to be solved

Explanation of the solution: Proposes a solution and explains how it will solve the problem

Evidence in support of the solution: Presents support for the proposed solution (this section is usually more than one paragraph)

Benefits of the solution: Explains the positive results of the proposed course of action

Refutation of opposing arguments: Addresses objections to the proposal

Conclusion: Reinforces the main point of the proposal; includes a strong concluding statement

![]() The following student essay contains all the elements of a proposal argument. The student who wrote this essay is trying to convince the college president that the school should adopt an honor code —a system of rules that defines acceptable conduct and establishes procedures for handling misconduct.

The following student essay contains all the elements of a proposal argument. The student who wrote this essay is trying to convince the college president that the school should adopt an honor code —a system of rules that defines acceptable conduct and establishes procedures for handling misconduct.

Grammar in Context

Will versus Would

Many people use the helping verbs will and would interchangeably. When you write a proposal, however, keep in mind that these words express different shades of meaning.

Will expresses certainty. In a list of benefits, for example, will indicates the benefits that will definitely occur if the proposal is accepted.

First, an honor code will create a set of basic rules that students can follow.

In addition, an honor code will promote honesty.

Would expresses probability. In a refutation of an opposing argument, for example, would indicates that another solution could possibly be more effective than the one being proposed.

Some people argue that a plagiarism-detection tool such as Turnitin.com would be simpler and a more effective way of preventing cheating than an honor code.

EXERCISE 15.6

EXERCISE 15.6

The following essay, “Self-Driving Cars Will Change the Rules of the Road” by Adam Cohen, includes the basic elements of a proposal argument. Read the essay, and answer the questions that follow it, consulting the outline on page 561 if necessary.

This opinion column appeared in Time on January 14, 2014.

ADAM COHEN

SELF-DRIVING CARS WILL CHANGE THE RULES OF THE ROAD

![]()

Not long ago, self-driving cars seemed like science fiction. But Google is now operating so-called autonomous cars in California and Nevada, and last week at the annual Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Toyota and Audi unveiled prototypes for self-driving cars to sell to ordinary car buyers. (Google co-founder Sergey Brin said last year he expects his company to have them ready for the general public within five years.) In a report backing self-driving cars, the consulting firm KPMG and the Center for Automotive Research recently predicted that driving is “on the brink of a new technological revolution.”1

But as the momentum for self-driving cars grows, one question is getting little attention: Should they even be legal? And if they are, how will the laws of driving have to adapt? All our rules about driving—from who pays for a speeding ticket to who is liable for a crash—are based on having a human behind the wheel. That is going to have to change.2

“Should they even be legal?”

There are some compelling reasons to support self-driving cars. Regular cars are inefficient: the average commuter spends 250 hours a year behind the wheel. They are dangerous. Car crashes are a leading cause of death for Americans ages 4 to 34 and cost some $300 billion a year. In the first 300,000 miles, Google reported that its cars had not had a single accident. Last August, one got into a minor fender bender, but Google said it occurred while someone was manually driving it.3

After heavy lobbying and campaign contributions, Google persuaded California and Nevada to enact laws legalizing self-driving cars. The California law breezed through the state legislature—it passed 37-0 in the senate and 74-2 in the assembly—and other states could soon follow. The Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, which represents big carmakers like GM and Toyota, opposed the California law, fearing it would make it too easy for carmakers and individuals to modify cars to self-drive without the careful protections built in by Google.4

That is a reasonable concern. If we are going to have self-driving cars, the technical specifications should be quite precise. Just because your neighbor Jeb is able to jerry-rig his car to drive itself using an old PC and some fishing tackle, that does not mean he should be allowed to.5

As self-driving cars become more common, there will be a flood of new legal questions. If a self-driving car gets into an accident, the human who is “co-piloting” may not be fully at fault—he may even be an injured party. Whom should someone hit by a self-driving car be able to sue? The human in the self-driving car or the car’s manufacturer? New laws will have to be written to sort all this out.6

How involved—and how careful—are we going to expect the human co-pilot to be? As a Stanford Law School report asks, “Must the ‘drivers’ remain vigilant, their hands on the wheel and their eyes on the road? If not, what are they allowed to do inside or outside, the vehicle?” Can the human in the car drink? Text-message? Read a book? Not surprisingly, the insurance industry is particularly concerned and would like things to move slowly. Insurance companies say all the rules of car insurance may need to be rewritten, with less of the liability put on those operating cars and more on those who manufacture them.7

At the signing ceremony for California’s self-driving-car law, Governor Jerry Brown was asked who is responsible when a self-driving car runs a red light. He answered: “I don’t know—whoever owns the car, I would think. But we will work that out. That will be the easiest thing to work out.” Google’s Brin joked, “Self-driving cars don’t run red lights.”8

Neither answer is sufficient. Self-driving cars should be legal—and they are likely to start showing up faster and in greater numbers than people expect. But if that is the case, we need to start thinking about the legal questions now. Given the high stakes involved in putting self-guided, self-propelled, high-speed vehicles on the road, “we will work that out” is not good enough.9

TIME and the TIME logo are registered trademarks of Time Inc. used Under License.

©2014. Time Inc. All rights reserved. Reprinted/Translated from TIME magazine and published with permission of Time Inc. Reproduction in any manner in any language in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited.

Identifying the Elements of a Proposal Argument

- What is the essay’s thesis statement? How effective do you think it is?

- Where in the essay does Cohen identify the problem he wants to solve?

- According to Cohen, what are the specific problems that self-driving cars solve?

- Where does Cohen present his solutions to the problems he identifies?

- Where does Cohen discuss the benefits of his proposal? What other benefits could he have addressed?

- Where does Cohen address possible arguments against his proposal? What other arguments might he have addressed? How would you refute each of these arguments?

- Evaluate the essay’s concluding statement.

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

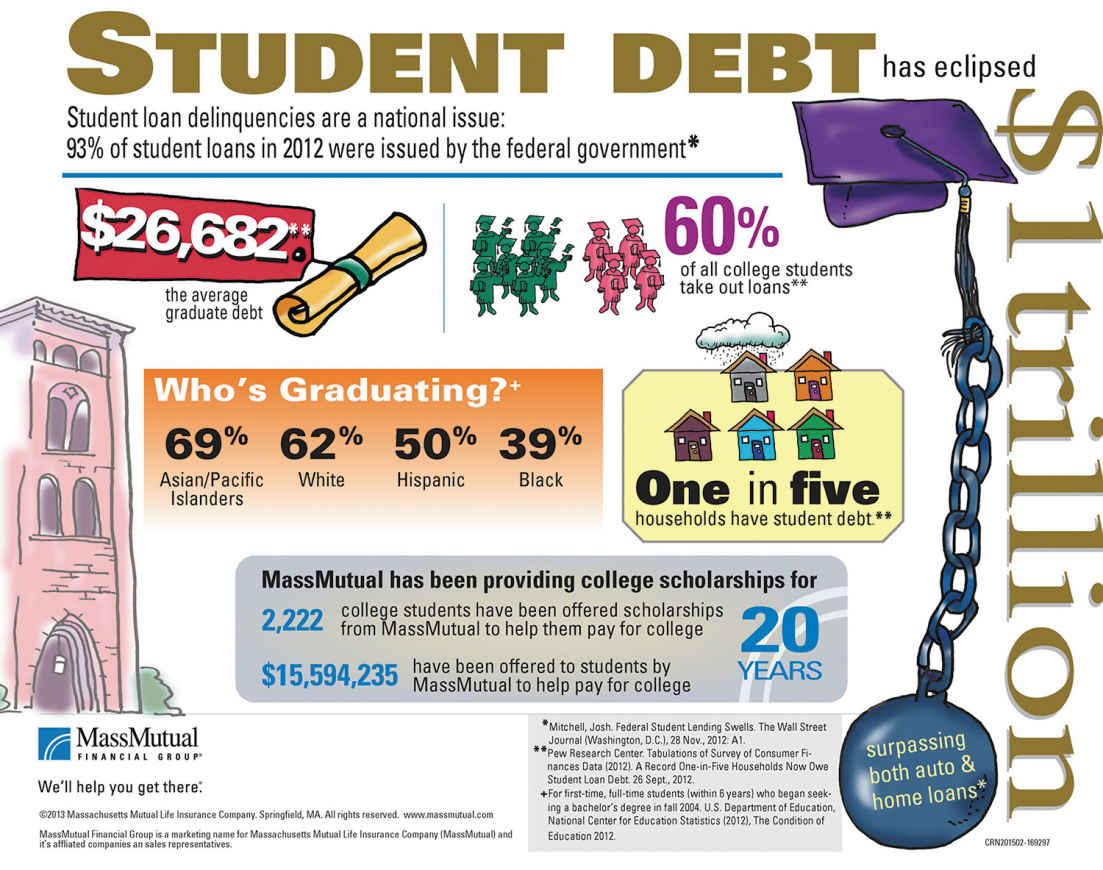

Should the Government Do More to Relieve the Student-Loan Burden?

Courtesy of Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance

Reread the At Issue box on page 551, which gives background on whether the government should do more to relieve the student-loan burden. Then, read the sources on the following pages.

As you read this material, you will be asked to answer questions and to complete some simple activities. This work will help you understand both the content and structure of the selections. When you are finished, you will be ready to write a proposal argument that makes a case for or against having the government do more to relieve the student-loan burden.

SOURCES

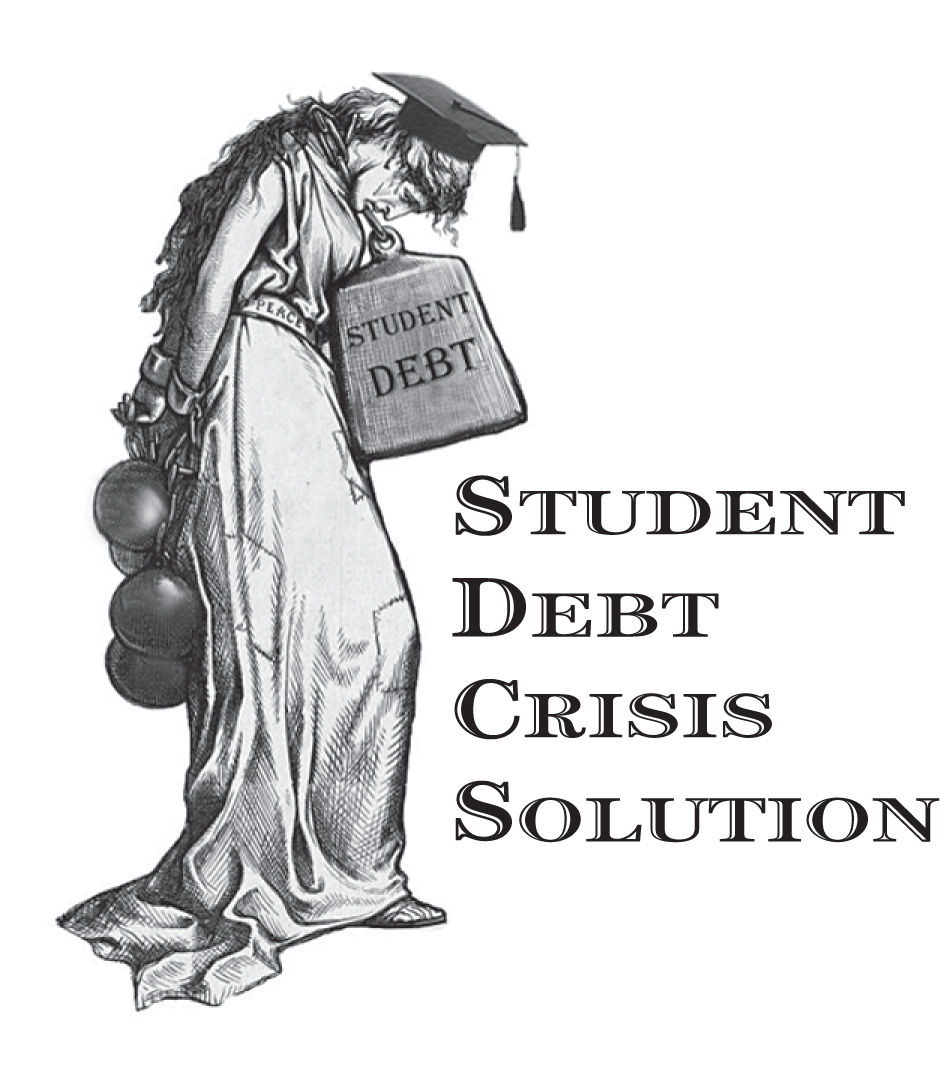

SovereignDollar.com, “Student Debt Crisis Solution” (editorial cartoon), p. 569

SovereignDollar.com, “Student Debt Crisis Solution” (editorial cartoon), p. 569 Richard Vedder, “Forgive Student Loans?,” p. 570

Richard Vedder, “Forgive Student Loans?,” p. 570 Kevin Carey, “The U.S. Should Adopt Income-Based Loans Now,” p. 573

Kevin Carey, “The U.S. Should Adopt Income-Based Loans Now,” p. 573 Astra Taylor, “A Strike against Student Debt,” p. 577

Astra Taylor, “A Strike against Student Debt,” p. 577 Lee Siegel, “Why I Defaulted on My Student Loans,” p. 580

Lee Siegel, “Why I Defaulted on My Student Loans,” p. 580 Sam Adolphsen, “Don’t Blame the Government,” p. 583

Sam Adolphsen, “Don’t Blame the Government,” p. 583

This editorial cartoon was adapted from an illustration in the Atlantic Monthly.

STUDENT DEBT CRISIS SOLUTION

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

- The editorial cartoon above shows Minerva, an ancient Roman goddess. Consult an encyclopedia to find out more about Minerva. Why do you think this mythical figure is used in this visual?

- Why are Minerva’s wrists chained? Why does she have a sign hanging from her neck? What point is the creator of this image trying to make?

- How could you use this visual to support an argument about student loans? What position do you think it could support?

- What argument does this editorial cartoon make?

The blog entry was posted to National Review Online on October 11, 2011.

RICHARD VEDDER

FORGIVE STUDENT LOANS?

As the Wall Street protests grow and expand beyond New York, growing scrutiny of the nascent movement is warranted. What do these folks want? Alongside their ranting about the inequality of incomes, the alleged inordinate power of Wall Street and large corporations, the high level of unemployment, and the like, one policy goal ranks high with most protesters: the forgiveness of student-loan debt. In an informal survey of over 50 protesters in New York last Tuesday, blogger and equity research analyst David Maris found 93 percent of them advocated student-loan forgiveness. An online petition drive advocating student-loan forgiveness has gathered an impressive number of signatures (over 442,000). This is an issue that resonates with many Americans.1

Economist Justin Wolfers recently opined that “this is the worst idea ever.” I think it is actually the second-worst idea ever—the worst was the creation of federally subsidized student loans in the first place. Under current law, when the feds (who have basically taken over the student-loan industry) make a loan, the size of the U.S. budget deficit rises, and the government borrows additional funds, very often from foreign investors. We are borrowing from the Chinese to finance school attendance by a predominantly middle-class group of Americans.2

But that is the tip of the iceberg: Though the ostensible objective of the loan program is to increase the proportion of adult Americans with college degrees, over 40 percent of those pursuing a bachelor’s degree fail to receive one within six years. And default is a growing problem with student loans.3

Further, it’s not clear that college imparts much of value to the average student. The typical college student spends less than 30 hours a week, 32 weeks a year, on all academic matters—class attendance, writing papers, studying for exams, etc. They spend about half as much time on school as their parents spend working. If Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa (authors of Academically Adrift) are even roughly correct, today’s students typically learn little in the way of critical learning or writing skills while in school.4

Moreover, the student-loan program has proven an ineffective way to achieve one of its initial aims, a goal also of the Wall Street protesters: increasing economic opportunity for the poor. In 1970, when federal student-loan and -grant programs were in their infancy, about 12 percent of college graduates came from the bottom one-fourth of the income distribution. While people from all social classes are more likely to go to college today, the poor haven’t gained nearly as much ground as the rich have: With the nation awash in nearly a trillion dollars in student-loan debt (more even than credit-card obligations), the proportion of bachelor’s-degree holders coming from the bottom one-fourth of the income distribution has fallen to around 7 percent.5

“The sins of the loan program are many. Let’s briefly mention just five.”

The sins of the loan program are many. Let’s briefly mention just five.6

First, artificially low interest rates are set by the federal government—they are fixed by law rather than market forces. Low-interest-rate mortgage loans resulting from loose Fed policies and the government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac spurred the housing bubble that caused the 2008 financial crisis. Arguably, federal student financial assistance is creating a second bubble in higher education.

Second, loan terms are invariant, with students with poor prospects of graduating and getting good jobs often borrowing at the same interest rates as those with excellent prospects (e.g., electrical-engineering majors at MIT).

Third, the availability of cheap loans has almost certainly contributed to the tuition explosion—college prices are going up even more than health-care prices.

Fourth, at present the loans are made by a monopoly provider, the same one that gave us such similar inefficient and costly monopolistic behemoths as the U.S. Postal Service.

Fifth, the student-loan and associated Pell Grant programs spawned the notorious FAFSA form that requires families to reveal all sorts of financial information—information that colleges use to engage in ruthless price discrimination via tuition discounting, charging wildly different amounts to students depending on how much their parents can afford to pay. It’s a soak-the-rich scheme on steroids.

Still, for good or ill, we have this unfortunate program. Wouldn’t loan forgiveness provide some stimulus to a moribund economy? The Wall Street protesters argue that if debt-burdened young persons were free of this albatross, they would start spending more on goods and services, stimulating employment. Yet we demonstrated with stimulus packages in 2008 and 2009 (not to mention the 1930s, Japan in the 1990s, etc.) that giving people more money to spend will not bring recovery. But even if it did, why should we give a break to this particular group of individuals, who disproportionately come from prosperous families to begin with? Why give them assistance while those who have dutifully repaid their loans get none? An arguably more equitable and efficient method of stimulus would be to drop dollars out of airplanes over low-income areas.7

Moreover, this idea has ominous implications for the macro economy. Who would take the loss from the unanticipated non-repayment of a trillion dollars? If private financial institutions are liable for some of it, it could kill them, triggering another financial crisis. If the federal government shoulders the entire burden, we are adding a trillion or so more dollars in liabilities to a government already grievously overextended (upwards of $100 trillion in liabilities counting Medicare, Social Security, and the national debt), almost certainly leading to more debt downgrades, which could trigger investor panic. This idea is breathtaking in terms of its naïveté and stupidity.8

The demonstrators say that selfish plutocrats are ruining our economy and creating an unjust society. Rather, a group of predominantly rather spoiled and coddled young persons, long favored and subsidized by the American taxpayer, are complaining that society has not given them enough—they want the taxpayer to foot the bill for their years of limited learning and heavy partying while in college. Hopefully, this burst of dimwittery should not pass muster even in our often dysfunctional Congress.9

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

- According to Vedder, forgiveness of student debt is “the second-worst idea ever” (para. 2). Why? What is the worst idea?

- In paragraphs 3–6, Vedder examines the weaknesses of the federally subsidized student-loan program. List some of the weaknesses he identifies.

- Why do you think Vedder waits until paragraph 7 to discuss debt forgiveness? Should he have discussed it sooner?

- Summarize Vedder’s primary objection to forgiving student debt. Do you agree with him? How would you refute his objection?

- Throughout his essay, Vedder uses rather strong language to characterize those who disagree with him. For example, in paragraph 8, he calls the idea of forgiving student loans “breathtaking in terms of its naïveté and stupidity.” In paragraph 9, he calls demonstrators “spoiled and coddled young persons” and labels Congress “dysfunctional.” Does this language help or hurt Vedder’s case? Would more neutral words and phrases have been more effective? Why or why not?

- How would Vedder respond to Astra Taylor’s solution to the student-loan crisis (p. 577)? Are there any points that Taylor makes with which Vedder might agree?

This commentary was published in the Chronicle of Higher Education on October 23, 2011.

KEVIN CAREY

The U.S. Should Adopt Income-Based Loans Now

A new generation of student debtors has seized the public stage. While the demands of the Occupy Wall Street movement are many, college lending reform is near the top of every list. Decades of greed, inattention, and failed policy have created a growing class of young men and women with few prospects of landing jobs good enough to bear the weight of their crushing college loans.1

Some activists have called for wholesale student-loan forgiveness—a kind of 21st-century jubilee. That’s unlikely. But there’s something the federal government can do right now to help students caught by our terribly unjust higher-education financing system: End all federal student-loan defaults forever by moving to income-contingent loans.2

The concept is simple. Right now, students pay back their loans on a fixed schedule, typically amortized over 10 years. Since people usually make less money early in their careers, their fixed monthly loan bill is hardest to manage in the first years after graduating (or not) from college. People unlucky enough to graduate during horrible recessions are even more likely to have bad jobs or no jobs and struggle paying back their loans. Not coincidentally, the U.S. Department of Education recently announced a sharp rise in loan defaults.3

Under an income-contingent loan system, like those in Australia and Britain, students pay a fixed percentage of their income toward their loans. Payments are automatically deducted from their paychecks by the IRS, just like income-tax withholding. Self-employed workers pay in quarterly installments, just as they do with their taxes. If borrowers earn a lot, their payments rise accordingly, and their loans are retired quickly. If their income falls below a certain level—say, the poverty line—they pay nothing. After an extended time period of 20 or 30 years, any remaining debt is forgiven.4

“Under an income-contingent loan system, … students pay a fixed percentage of their income toward their loans.”

In other words, nobody ever defaults on a federal student loan again. The whole concept of “default” is expunged from the system. No more collection agencies hounding people with 10 phone calls a night. No more ruined credit and dashed hopes of home-ownership. People who want to enter virtuous but lower-paid professions like social work and teaching won’t be deterred by unmanageable debt.5

And by calibrating interest and payment rates, the federal government can make the program no more expensive than the current cost of subsidizing loans and writing off unpaid debt. The only losers are the repo men.6

The concept has been proven to work—Australia and Britain have used it for years—and both liberals and conservatives have reason to get on board. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman proposed the idea all the way back in 1955.7

Indeed, income-contingent loans are such a good idea, one might wonder why they don’t exist already. Historically, administrative complications have been a major culprit. Until last year, the federal government managed most student loans by paying private banks to act as lenders and then guaranteeing their losses. The IRS would have had to maintain relationships with scores of different lenders, relying on banks for notification of who owes how much and disbursing money hither and yon. Income-contingent loans would have created a huge bureaucratic headache.8

But in 2010, Congress abolished the old system, cutting out private banks. Now the federal government originates all federal loans. The IRS would have to deal with only one lender: the U.S. Department of Education. In other words, there is a new opportunity to overhaul the way students repay their college debt that didn’t exist until this year.9

It’s true that students who pay over long periods of time will pay more interest and that the taxpayers will bear the cost of partially forgiven loans. But under the current system the federal government is already eating the cost of defaulted loans, and low-income students who can’t repay loans are often hit with fines and penalties that dwarf the cost of extra interest.10

When federal loans were first created, nobody imagined they would become standard practice for financing college. As late as 1993, most undergraduates didn’t borrow. Now, two-thirds take on debt, and most of those loans are federal. The average debt load increased over 50 percent during that time.11

Nor is repayment an isolated problem. One recent study found that the majority of American borrowers—56 percent—struggled with loan payments in the first five years after college. In Britain, by contrast, 98 percent of borrowers are meeting their obligations.12

Because student loans can almost never be discharged in bankruptcy, defaulted loans can haunt students for a lifetime. Some senior citizens theoretically could have their Social Security checks garnished to make good on old student debt. That is insane.13

A similar-sounding federal program, called income-based repayment, is now on the books and is scheduled to become somewhat more generous starting in 2014. But the program is administratively complicated, involving income-eligibility caps and requiring students to reapply every year. This points to another major advantage of income-contingent loans: simplicity.14

Even with the government as the sole source of federal loans, many graduates still have to navigate a thicket of different rates, terms, lenders, consolidation options, and schedules in order to meet their obligations. Some fall behind not because they’re unwilling or unable to pay, but because they can’t get the right check to the right place at the right time. An income-contingent system would remove all of that hassle, making repayment simple and automatic, and setting college graduates free to get on with the important business of starting their lives.15

The student-loan system has grown into an out-of-control monster tearing at the fabric of civil society. In Chile, student anger over an inequitable, unaffordable, profit-oriented higher-education system led to nationwide pro-tests and violent confrontation just months ago. Now the seeds of similar unrest are sprouting here.16

Income-contingent loans won’t solve the escalating college prices, state disinvestment in higher education, and overall economic weakness that are driving more students into debt. But they offer a simpler, fairer, more efficient, and more humane way of allowing students to repay loans that aren’t disappearing from the higher-education landscape anytime soon. They could be put in place quickly at no extra cost to the taxpayer. In a dismal fiscal environment, there are few deals this good.17

The students at the barricades are right to be angry. They didn’t run the economy into the ditch. They didn’t create the system in which a college degree is all but mandatory to pursue a good career, and loans are often unavoidable. But they have to live with it. Income-contingent loans are one way to give them the help they need.18

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

- Carey blames the current student-loan problem on years of “greed, inattention, and failed policy” (para. 1). Is he right to assume his readers will agree with him, or should he have provided evidence to support this statement? Explain.

- In paragraph 2, Carey says that income-contingent loans would end “forever” all student-loan defaults. After reading Carey’s explanation, how would you define income-contingent loans?

- What evidence does Carey present to support his proposal? If income-contingent loans are such a good idea, why hasn’t the government tried them before?

- What kind of appeal does Carey make in paragraph 7? In your opinion, how effective is this appeal?

- Where does Carey address arguments against his proposal? List these arguments. Which argument do you think presents the most effective challenge to Carey’s position? Why?

- In paragraph 16, Carey calls the student-loan system “an out-of-control monster tearing at the fabric of civil society.” In paragraph 18, he says, “The students at the barricades are right to be angry.” Do you think he is exaggerating, or is this strong language justified?

- In paragraph 17, Carey lists problems that income-contingent loans will not solve. Does this paragraph undercut (or even contradict) his statement in paragraph 2 that income-contingent loans would end student-loan defaults? Explain.

Taylor’s op-ed appeared on February 27, 2015, in the New York Times.

ASTRA TAYLOR

A STRIKE AGAINST STUDENT DEBT

This week a group of former students calling themselves the Corinthian 15 announced that they were committing a new kind of civil disobedience: a debt strike. They are refusing to make any more payments on their federal student loans.1

Along with many others, they found themselves in significant debt after attending programs at the Corinthian Colleges, a collapsed chain of for-profit schools that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has accused of running a “predatory lending scheme.” While the bureau has announced a plan to reduce some of the students’ private loan debts, the strikers are demanding that the Department of Education use its authority to discharge their federal loans as well.2

These 15 students are members of the Debt Collective, an organization that evolved out of a project I helped start in 2012 called the Rolling Jubilee. Until now, we have worked in the secondary debt market, using crowdfunded donations to buy portfolios of medical and educational debts for pennies on the dollar, just as debt collectors do.3

Only, instead of collecting on them, we abolish them, operating under the belief that people shouldn’t go into debt for getting sick or going to school. This week, we erased $13 million of “unpaid tuition receivables” belonging to 9,438 people associated with Everest College, a Corinthian subsidiary.4

But this approach has its limits. Federal loans, for example, are guaranteed by the government, and debtors can be freed of them—via bankruptcy—only under exceedingly rare circumstances. That means they aren’t sold at steep discounts and remain out of our reach. What’s more, America’s mountain of student debt is too immense for the Jubilee to make a significant dent in it.5

Real change will require more organized actions like those taken by the Corinthian 15.6

If anyone deserves debt relief—morally and legally—it’s these students. For-profit colleges are notorious for targeting low-income minorities, single mothers, and veterans with high-pressure, misleading recruitment techniques. The schools slurp up about a quarter of all federal student aid money, more than $30 billion a year, while their students run up a lifetime of debt for a degree arguably worth no more than a high school diploma.7

“If anyone deserves debt relief—morally and legally—it’s these students.”

But for-profit schools aren’t the only problem. Degrees earned from traditional colleges can also leave students unfairly burdened.8

Today, a majority of outstanding student loans are in deferral, delinquency, or default. As state funding for education has plummeted, public colleges have raised tuition. Private university costs are skyrocketing, too, rising roughly 25 percent over the last decade. That’s why every class of graduates is more in the red than the last.9

Modest fixes are not enough. Consider the interest rate tweaks or income-based repayment plans offered by the Obama administration. They lighten the debt burden on some—but not everyone qualifies. They do nothing to address the $165 billion private loan market, where interest rates are often the most punishing, or how higher education is financed.10

Americans now owe $1.2 trillion in student debt, a number predicted by the think tank Demos to climb to $2 trillion by 2025. What if more people from all types of educational institutions and with all kinds of debts followed the example of the Corinthian 15, and strategically refused to pay back their loans? This would transform the debts into leverage to demand better terms, or even a better way of funding higher education altogether.11

The quickest fix would be a full-scale student debt cancellation. For students at predatory colleges like Corinthian, this could be done immediately by the Department of Education. For the broader population of students, it would most likely take an act of Congress.12

Student debt cancellation would mean forgone revenue in the near term, but in the long term it could be an economic stimulus worth much more than the immediate cost. Money not spent paying off loans would be spent elsewhere. In that situation, lenders, debt collectors, servicers, guaranty agencies, asset-backed security investors, and others who profit from student loans would suffer the most from debt forgiveness.13

We also need to bring back the option of a public, tuition-free college education once represented by institutions like the University of California, which charged only token fees. By the Rolling Jubilee’s estimate, every public two- and four-year college and university in the United States could be made tuition-free by redirecting all current educational subsidies and tax exemptions straight to them and adding approximately $15 billion in annual spending.14

This might sound like a lot, but it’s a small price to pay to restore America’s place on the long list of countries that provide tuition-free education.15

To get there, more groups like the Corinthian 15 will have to show that they are willing to throw a wrench in the gears of the system by threatening to withhold payment on their debt. Everyone deserves a quality education. We need to come up with a better way to provide it than debt and default.16

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

- Taylor begins her essay by discussing the Corinthian 15. How does this focus help her introduce the problem she wants to solve?

- Paraphrase Taylor’s thesis by filling in the following template.

The Department of Education should solve the student debt crisis by

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________.

- What two problems does Taylor discuss? Does she describe them in enough detail? Explain.

- What solutions does Taylor offer? How feasible are these solutions?

- At what points in her essay does Taylor address objections to her proposal? Does she address the most important objections? If not, what other objections should she have addressed?

- Taylor uses three terms that might be unfamiliar to some readers.

secondary debt market (para. 3)

crowdfunded donations (3)

unpaid tuition receivables (4)

Look up these terms, and then reread the paragraphs in which they appear. Do these terms help Taylor develop her argument, or could she have made her points without them?

- What assumptions does Taylor assume are self-evident and need no proof? Do you agree? If not, what evidence should Taylor have included to support these assumptions?

The New York Times ran this article on June 6, 2015.

LEE SIEGEL

WHY I DEFAULTED ON MY STUDENT LOANS

One late summer afternoon when I was seventeen, I went with my mother to the local bank, a long-defunct institution whose name I cannot remember, to apply for my first student loan. My mother co-signed. When we finished, the banker, a balding man in his late fifties, congratulated us, as if I had just won some kind of award rather than signed away my young life.1

By the end of my sophomore year at a small private liberal arts college, my mother and I had taken out a second loan, my father had declared bankruptcy, and my parents had divorced. My mother could no longer afford the tuition that the student loans weren’t covering. I transferred to a state college in New Jersey, closer to home.2

Years later, I found myself confronted with a choice that too many people have had to and will have to face. I could give up what had become my vocation (in my case, being a writer) and take a job that I didn’t want in order to repay the huge debt I had accumulated in college and graduate school. Or I could take what I had been led to believe was both the morally and legally reprehensible step of defaulting on my student loans, which was the only way I could survive without wasting my life in a job that had nothing to do with my particular usefulness to society.3

I chose life. That is to say, I defaulted on my student loans.4

As difficult as it has been, I’ve never looked back. The millions of young people today, who collectively owe over $1 trillion in loans, may want to consider my example.5

It struck me as absurd that one could amass crippling debt as a result, not of drug addiction or reckless borrowing and spending, but of going to college. Having opened a new life to me beyond my modest origins, the education system was now going to call in its chits and prevent me from pursuing that new life, simply because I had the misfortune of coming from modest origins.6

Am I a deadbeat? In the eyes of the law I am. Indifferent to the claim that repaying student loans is the road to character? Yes. Blind to the reality of countless numbers of people struggling to repay their debts, no matter their circumstances, many worse than mine? My heart goes out to them. To my mind, they have learned to live with a social arrangement that is legal, but not moral.7

“Am I a deadbeat?”

Maybe the problem was that I had reached beyond my lower-middle-class origins and taken out loans to attend a small private college to begin with. Maybe I should have stayed at a store called The Wild Pair, where I once had a nice stable job selling shoes after dropping out of the state college because I thought I deserved better, and naïvely tried to turn myself into a professional reader and writer on my own, without a college degree. I’d probably be district manager by now.8

Or maybe, after going back to school, I should have gone into finance, or some other lucrative career. Self-disgust and lifelong unhappiness, destroying a precious young life—all this is a small price to pay for meeting your student loan obligations.9

Some people will maintain that a bankrupt father, an impecunious background, and impractical dreams are just the luck of the draw. Someone with character would have paid off those loans and let the chips fall where they may. But I have found, after some decades on this earth, that the road to character is often paved with family money and family connections, not to mention 14 percent effective tax rates on seven-figure incomes.10

Moneyed stumbles never seem to have much consequence. Tax fraud, insider trading, almost criminal nepotism—these won’t knock you off the straight and narrow. But if you’re poor and miss a child-support payment, or if you’re middle class and default on your student loans, then God help you.11

Forty years after I took out my first student loan, and thirty years after getting my last, the Department of Education is still pursuing the unpaid balance. My mother, who co-signed some of the loans, is dead. The banks that made them have all gone under. I doubt that anyone can even find the promissory notes. The accrued interest, combined with the collection agencies’ opulent fees, is now several times the principal.12

Even the Internal Revenue Service understands the irrationality of pursuing someone with an unmanageable economic burden. It has a program called Offer in Compromise that allows struggling people who have fallen behind in their taxes to settle their tax debt.13

The Department of Education makes it hard for you, and ugly. But it is possible to survive the life of default. You might want to follow these steps: Get as many credit cards as you can before your credit is ruined. Find a stable housing situation. Pay your rent on time so that you have a good record in that area when you do have to move. Live with or marry someone with good credit (preferably someone who shares your desperate nihilism).14

When the fateful day comes, and your credit looks like a war zone, don’t be afraid. The reported consequences of having no credit are scare talk, to some extent. The reliably predatory nature of American life guarantees that there will always be somebody to help you, from credit card companies charging stratospheric interest rates to subprime loans for houses and cars. Our economic system ensures that so long as you are willing to sink deeper and deeper into debt, you will keep being enthusiastically invited to play the economic game.15

I am sharply aware of the strongest objection to my lapse into default. If everyone acted as I did, chaos would result. The entire structure of American higher education would change.16

The collection agencies retained by the Department of Education would be exposed as the greedy vultures that they are. The government would get out of the loan-making and the loan-enforcement business. Congress might even explore a special, universal education tax that would make higher education affordable.17

There would be a national shaming of colleges and universities for charging soaring tuition rates that are reaching lunatic levels. The rapacity of American colleges and universities is turning social mobility, the keystone of American freedom, into a commodified farce.18

If people groaning under the weight of student loans simply said, “Enough,” then all the pieties about debt that have become absorbed into all the pieties about higher education might be brought into alignment with reality. Instead of guaranteeing loans, the government would have to guarantee a college education. There are a lot of people who could learn to live with that, too.19

![]() At Issue: Sources for Developing a Proposal Argument

At Issue: Sources for Developing a Proposal Argument

- In the first three paragraphs of his essay, Siegel discusses the reasons he decided to default on his student loans. How convincing are these reasons? Explain.

- In paragraph 5, Siegel says, “As difficult as it has been, I’ve never looked back.” Does his essay contradict this statement in any way?

- Throughout his essay, Siegel discusses possible objections to his decision. For example, in paragraph 7, he admits that he is “a deadbeat.” List all the objections he attempts to refute. How effectively does he refute them? For example, does he ever convince you that he is not a deadbeat?

- What is Siegel’s opinion of banks? Of colleges and universities? Of the Department of Education? Of American life? How do these opinions color his discussion?

- Siegel’s essay can be read as a proposal. Fill in the template below, paraphrasing Siegel’s thesis statement and key points.

Thesis Statement: ___________________________________________.

Explanation of the Problem: __________________________________.

Explanation of the Solution: __________________________________.

Benefits of the Solution: ______________________________________.

Refutation of Opposing Arguments: ___________________________.

- How does the fact that Siegel is the author of five books and is now almost sixty years of age affect his credibility? Does this information make you more or less likely to see his call to action as reasonable?

This opinion piece was published online on May 1, 2012, at TheMaineWire.com.

SAM ADOLPHSEN

DON’T BLAME THE GOVERNMENT

I still remember the day.1

I was sitting at my kitchen table, pen in hand, and I signed the dotted line to borrow a significant amount of money to pay for my first year of college.2

The funny thing was, despite what you might hear in the media these days, no one was standing over my shoulder forcing me to. No government official told me I had to borrow the money. It was my decision then and it’s my debt today. I weighed the price of borrowing against the value of a secondary degree, and I chose education.3

My decision, my responsibility.4

That’s not what you are hearing today from most of America’s youth though. There are rallies in the streets of Portland, and in cities across America, with “Occupy” inspired students and graduates whining about their debt and how they need a way out. Students that have borrowed too much, of their own free will, for degrees that haven’t led to a job, are now demanding a handout.5

My generation is looking for a bailout. It doesn’t matter that many of them are in tough positions, loaded with debt, because they made poor choices. It doesn’t matter that borrowing money is a personal decision and requires personal responsibility. They want the easy way out.6

Take the example of Stephanie, featured in a recent story from the Philadelphia Inquirer that re-ran in the Portland Press Herald. Stephanie, the story laments, owes over $100,000 in student loans. Poor Stephanie. Then we find out that, for one, Stephanie is in law school (really, becoming a lawyer costs money? Who knew …) and even worse, we find out that Stephanie, had a FREE RIDE to Rutgers, but instead chose to borrow money to go to a smaller private school because she “fell in love with it.”7

“They want the easy way out.”

So Stephanie didn’t have to take on student loan debt. She chose to. Why should I feel sorry for her? Why should the government lower her interest rates so taxpayers can help her pay those loans back? It’s her debt. Not the taxpayers of America.8

Other decisions factor into this discussion as well. The Press Herald ran another story a couple days ago, highlighting several students who carried student loan debt. One of the students was a Social Worker who owes $97,000 in student loan debt. A cursory search of the Internet will tell you that social workers don’t earn enough to warrant that kind of debt. The same goes for a Maine student who will owe more than $27,000 for his degree in Philosophy.9

Seriously, I know Walt Disney told my generation we can “be whatever we want to be” if we “believe in ourselves” but borrowing $27,000 for a career in philosophy … in Maine? That’s a questionable decision at best, and it’s not the government’s fault.10

The government already stepped in quietly and took over the student loan industry as part of Obamacare, and they already used taxpayer money to lower interest rates on current government student loans to 3.4 percent. Now those taxpayer subsidized interest rates are set to expire, and more than double, and the “gimme gimme” nation doesn’t like it.11

Naturally, those who want government to take care of them are calling for the interest rates to be held at 3.4 percent, with the taxpayers chipping in for the difference. But make no mistake, even if those rates are held, this won’t be the end of the discussion. Now that the government holds all student loans, they have the opportunity to “bail out students” by forgiving loans. “Occupy” camps in a park near you are already chanting to the beat of the “forgive all student loans” drum, and you can expect that cry to get louder this summer. (It’s warm so they can start “occupying” again.)12

Now don’t get me wrong. I agree that college costs are too high. And that IS partly government’s fault. Consider the University of Maine, piling on raises for their teachers, while simultaneously jacking up rates for students. In just a few years, university salaries were up 29 percent overall while at the same time tuition costs jumped 30 percent. That’s unacceptable and it’s a problem that needs to be addressed.13

It’s also the government’s fault that anybody considers a bailout a legitimate solution to our problems. The bank bailouts and Obama’s absolute boondoggle “American Recovery Act” set the precedent and taught my generation that poor decisions and failure can be fixed with a government check. Shame on them for that, and shame on us for looking to government to bail out students now.14

Ultimately, students and their parents make the decision to borrow money for school. And it’s their responsibility to pay it back. I’m tired of the whining, I’m tired of the blame game, and I’m tired of people relying on government to bail them out.15

It’s your debt. Pay it yourself.16

![]() At Issue: Sources for Developing a Proposal Argument

At Issue: Sources for Developing a Proposal Argument

- Adolphsen states his thesis in paragraph 4: “My decision, my responsibility.” In your own words, write an alternate one-sentence thesis statement for this essay on the lines below.

Thesis Statement: _____________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________.

Is your thesis more or less effective than Adolphsen’s? Explain.

- Adolphsen uses two examples to support his point that some people in his generation “want the easy way out” (para. 6). Are these examples enough to support his point? What other evidence could he have provided?

- Could Adolphsen be accused of oversimplifying a complex issue? In other words, does he make hasty or sweeping generalizations? Does he beg the question? If so, where?

- Where in his essay does Adolphsen concede a point to those who disagree with him? How effectively does he deal with this point?

- How does Adolphsen characterize those who want student-debt relief? Are his characterizations fair? Accurate? Do these characterizations help or hurt his credibility? Explain.

- In what sense is Adolphsen’s essay a refutation of Lee Siegel’s essay (p. 580)?

TEMPLATE FOR WRITING A PROPOSAL ARGUMENT

Write a one-paragraph proposal argument in which you consider the topic, “Should the Government Do More to Relieve the Student-Loan Burden?” Follow the template below, filling in the blanks to create your proposal.

The current federal student-loan program has some problems that must be addressed. For example, _________________________________________ __________________________________. In order to address this situation, ______________________________________________________________________. First, _______________________________________________________________. _______________________________________________________________________. ________________________________________________________________ Second, ________________________________________________________________________ ________________. Finally, _____________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________. Not everyone agrees that this is the way to solve these problems, however. Some say ________ ________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________. Others point out that _______________ _______________________________________________________________________. These objections make sense, but ______________________________________. _________________________________. All in all, _________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________.

EXERCISE 15.7

EXERCISE 15.7

Ask several of your instructors and your classmates whether they think the government should do more to relieve the student-loan burden. Then, add their responses to the paragraph you wrote using the template above.

EXERCISE 15.8

EXERCISE 15.8

Write a proposal arguing that the government should do more to relieve the student-loan burden. Be sure to present examples from your own experience to support your arguments. (If you like, you may incorporate the material you developed for the template and for Exercise 15.7 into your essay.) Cite the readings on pages 569–585, and be sure to document your sources and include a works-cited page. (See Chapter 10 for information on documenting sources.)

EXERCISE 15.9

EXERCISE 15.9

Review the four pillars of argument discussed in Chapter 1. Does your essay include all four elements of an effective argument? Add anything that is missing.

WRITING ASSIGNMENTS: PROPOSAL ARGUMENTS

WRITING ASSIGNMENTS: PROPOSAL ARGUMENTS

- Each day, students at college cafeterias throw away hundreds of pounds of uneaten food. A number of colleges have found that by simply eliminating the use of trays, they can cut out much of this waste. At one college, for example, students who did not use trays wasted 14.4 percent less food for lunch and 47.1 percent less for dinner than those who did use trays. Write a proposal to your college or university in which you recommend eliminating trays from dining halls. Use your own experiences as well as information from your research and from interviews with other students to support your position. Be sure to address one or two arguments against your position.

- Look around your campus, and find a service that you think should be improved. It could be the financial aid office, the student health services, or the writing center. Then, write an essay in which you identify the specific problem (or problems) and suggest a solution. If you wish, interview a few of your friends to get some information that you can use to support your proposal.

- Assume that your college or university has just received a million-dollar donation from an anonymous benefactor. Your school has decided to solicit proposals from both students and faculty on ways to spend the money. Write a proposal to the president of your school in which you identify a good use for this windfall. Make sure you identify a problem, present a solution, and discuss the advantages of your proposal. If possible, address one or two arguments against your proposal—for example, that the money could be put to better use somewhere else.