Establishing Feasibility

Your solution not only has to make sense but also has to be feasible —that is, it has to be practical. Sometimes a problem can be solved, but the solution may be almost as bad as—or even worse than—the problem. For example, a city could drastically reduce crime by putting police on every street corner, installing video cameras at every intersection, and stopping and searching all cars that contain two or more people. These actions would certainly reduce crime, but most people would not want to live in a city that instituted such authoritarian policies.

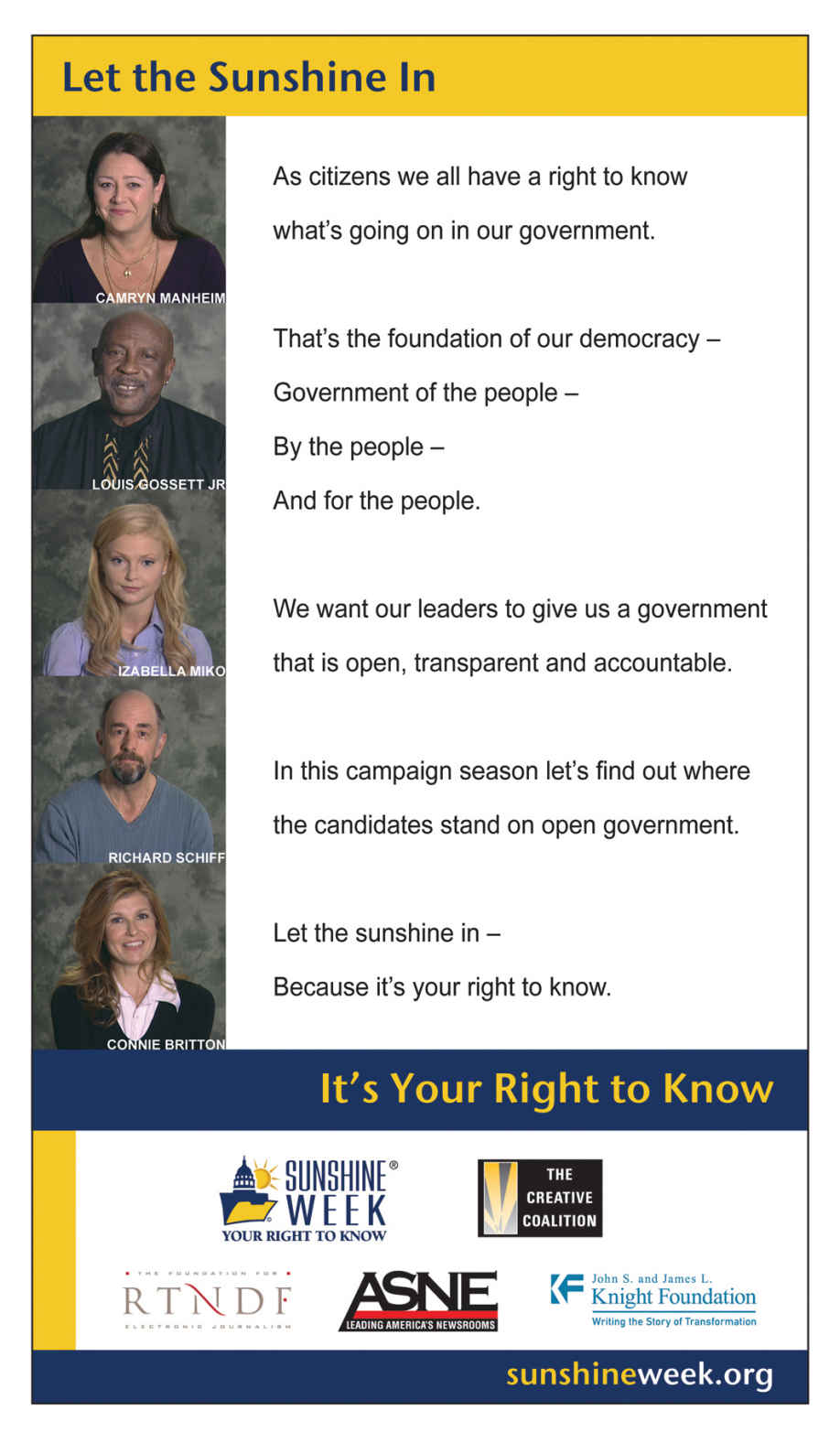

Advocacy groups frequently publish proposals.

© 2009 Sunshine Week/American Society of News Editors (asne.org). All rights reserved.

Even if a solution is desirable, it still may not be feasible. For example, although expanded dining facilities might improve life on campus, the cost of a new student cafeteria would be high. If paying for it means that tuition would have to be increased, many students would find this proposal unacceptable. On the other hand, if you could demonstrate that the profits from the increase in food sales in the new cafeteria would offset its cost, then your proposal would be feasible.