Structuring an Evaluation Argument

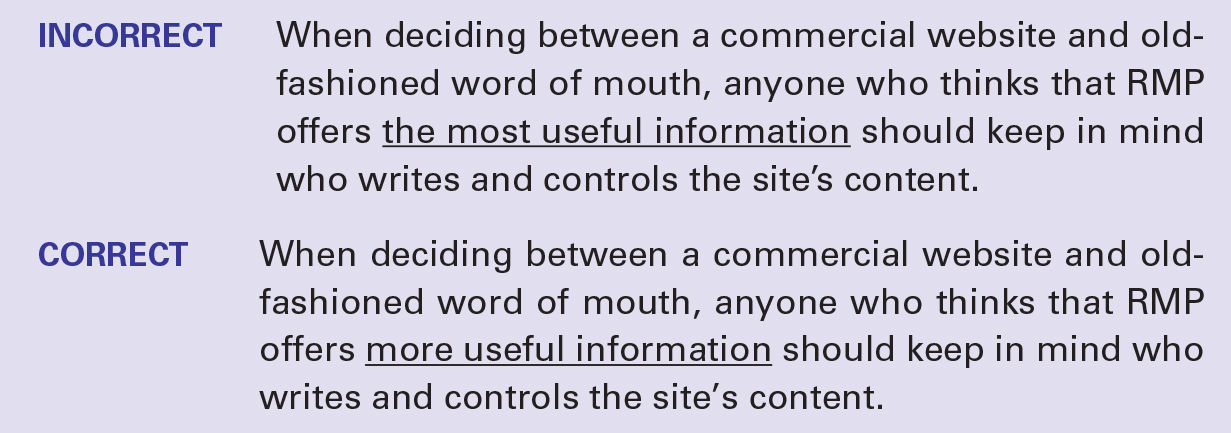

In general terms, an evaluation argument can be structured like this:

Introduction: Establishes the criteria by which you will evaluate your subject; states the essay’s thesis

Evidence (first point in support of thesis): Supplies facts, opinions, and so on to support your evaluation in terms of one of the criteria you have established

Evidence (second point in support of thesis): Supplies facts, opinions, and so on to support your evaluation in terms of one of the criteria you have established

Evidence (third point in support of thesis): Supplies facts, opinions, and so on to support your evaluation in terms of one of the criteria you have established

Refutation of opposing arguments: Presents others’ evaluations and your arguments against them

Conclusion: Reinforces the main point of the argument; includes a strong concluding statement

![]() The following student essay includes all the elements of an evaluation argument. The student who wrote the essay was evaluating a popular website, RateMyProfessors.com.

The following student essay includes all the elements of an evaluation argument. The student who wrote the essay was evaluating a popular website, RateMyProfessors.com.

GRAMMAR IN CONTEXT

Comparatives and Superlatives

When you write an evaluation argument, you make judgments, and these judgments often call for comparative analysis—for example, arguing that one thing is better than another or the best of its kind.

When you compare two items or qualities, you use a comparative form: bigger, better, more interesting, less realistic. When you compare three or more items or qualities, you use a superlative form: the biggest, the best, the most interesting, the least realistic. Be careful to use these forms appropriately.

Do not use the comparative when you are comparing more than two things.

The incorrect version reads, “Perhaps these kinds of feedback do not attract advertisers; comments about a professor’s “Hotness”- the less important measure of effectiveness-apparently does.”, with “the less important measure” underlined. The correct version reads, “Perhaps these kinds of feedback do not attract advertisers; comments about a professor’s “Hotness” - the least important measure of effectiveness - apparently does.”, with “the least important measure” underlined.

Do not use the superlative when you are comparing only two things.

The incorrect version reads, “When deciding between a commercial website and old fashioned word of mouth, anyone who thinks that RMP offers the most useful information should keep in mind who writes and controls the site’s content.”, with “the most useful information” underlined. The correct version reads, “When deciding between a commersical website and old-fasioned word of mouth, anyone who thinks that RMP offers more useful information should keep in mind who writes and controls the site’s content.”, with “more useful information” underlined.

EXERCISE 14.5

EXERCISE 14.5

The following commentary, “Nothing Pretty in Child Pageants,” includes the basic elements of an evaluation argument. Read the essay, and then answer the questions that follow it, consulting the outline on pages 521–522 if necessary.

This article was published in the Lexington Herald-Leader on August 14, 2011.

Vernon R. Wiehe

Nothing Pretty in child pageants

Toddlers and Tiaras is a televised beauty pageant for very young children which appears weekly ironically on The Learning Channel. The Web site for the show describes it this way: “On any given weekend, on stages across the country, little girls and boys parade around wearing makeup, false eyelashes, spray tans, and fake hair to be judged on their beauty, personality, and costumes. Toddlers and Tiaras follows families on their quest for sparkly crowns, big titles, and lots of cash.”1

A TV viewer will see the program’s feeble attempts at Las Vegas-like glamour and glitz in a rented hotel ballroom or school auditorium with primarily little girls in adult-like pageant attire parading in front of a small audience consisting largely of participants’ families. The tots’ attire includes makeup, hair extensions, and “flippers” to hide missing teeth. Mothers, often overweight, engage in silly antics coaching the children in every move of their routines with the hope of winning a trophy taller than the child, a rhinestone crown, the title of “Ultimate Grand Supreme,” and possibly some cash.2

The viewer will also be taken behind the scenes to witness temper tantrums from children resisting the role into which they are being put. On a recent show, a 2-year-old cried the entire time on stage; in another show, a mother literally dragged the child around the stage supposedly putting the child through her routine.3

It raises questions for the viewer: Whose idea is this—the child’s or the adult’s? Is participating in such pageants age-appropriate behavior for a small child? Might such participation even represent a potential danger for the child’s emotional development?4

The potential impact of child beauty pageants may be viewed in terms of the fallacious arguments most frequently cited in support of this activity:5

All Little Girls Like to Play Dress-Up at Some Time

Dress-up, a sign of a child identifying with or mimicking the mother, is significantly different from organized child beauty pageants.6

First, dress-up play generally is an activity engaged in by a young girl alone or with a group of playmates at home rather than on a stage in front of an audience.7

Second, competition, an important element in child beauty pageants, ranks contestants, with one child becoming a winner and the others losers.8

Third, dress-up involves little girls wearing their mothers’ cast-off clothing or cosmetics in a way the child perceives mother uses these objects. Participants in Toddlers and Tiaras spend hundreds and even thousands of dollars for costumes, cosmetics, and even beauty consultants.9

Parents certainly have a right to spend their money on children as they wish, but if this expenditure of money and effort is for the ultimate goal of the child winning the contest and the child fails to do so, what is the emotional cost to the child? What happens to the child’s self-esteem?10

Children’s Beauty Pageants Teach Poise and Self-Confidence

Even if the pageants do foster the development of these attributes, the question must be raised whether poise and self-confidence stemming from beauty pageants is age appropriate for the child. One of the most dangerous aspects of these pageants is the sexualization of young girls.11

Sexualization occurs through little girls wearing adult women’s clothing in diminutive sizes, the use of makeup which often is applied by makeup consultants, spray tanning the body, the dying of hair and the use of hair extensions, and assuming provocative postures more appropriate for adult models.12

The sexualization of young children sends a conflicting message to the child and a dangerous message to adults. To the child, a message is given that sexuality—expressed in clothing, makeup, and certain postures—is appropriate and even something to exploit. The message to adults, especially pedophiles, is one condoning children as sexual objects. Research on child sexual abuse shows that the sexualization of children is a contributing factor to their sexual abuse.13

Children Enjoy Participating in Beauty Pageants

While young children may express enjoyment in participating in pageants, children are eager to please adults. Sleeping with their hair in curlers, having to sit quietly while their hair is being tinted or rolled, fake nails being applied, or their body being spray tanned hardly seems like activities very young girls would choose over having fun with friends in age-appropriate play. The negative reactions of many of the participants in Toddlers and Tiaras testify to this.14

Participation in Beauty Pageants Is No Different from Participating in Athletic or Suzuki Music Education Programs

Children’s athletic programs and music education programs teach skills appropriate to the developmental stage of the child upon which the child can build later in life rather than emphasizing the beauty of the human body that can change significantly with time. In Suzuki recitals, for example, the unique contribution of each child is recognized and no child loses.15

Do child beauty pageants constitute child abuse?16

“Do child beauty pageants constitute child abuse?”

This question must be answered on an individual basis. Parents who force their children to participate in pageants, as well as in athletic and music education programs, can be emotionally and even physically abusive, if participation is meeting parental needs rather that the needs of the child.17

The risk for such abuse to occur is perhaps greatest when children are not recognized for what they are—children—but rather are forced to assume miniature adult roles.18

Play is an important factor in children’s early development because, through play, they learn skills for adulthood.19

After all, what is the rush to become an adult?20

Identifying the Elements of an Evaluation Argument

- Wiehe does not state his thesis directly. Write a thesis statement for this essay by filling in the template below. (Hint: Try answering the questions Wiehe asks in paragraph 4.)

Because _________________________________________________________________________________________________________, beauty pageants are bad for children.

- What criteria does Wiehe use to evaluate child beauty pageants? If he wanted to make the opposite case, what criteria might he use instead?

- In his essay’s boldface headings, Wiehe identifies four opposing arguments. Which of these opposing arguments do you think presents the strongest challenge to Wiehe’s position? Why?

- Do you think Wiehe expects his readers to have seen the program Toddlers and Tiaras? Does he expect them to have strong feelings about child beauty pageants? How can you tell?

- After he has refuted arguments against his position, Wiehe (a professor emeritus of social work) begins a discussion of whether “child beauty pageants constitute child abuse” (para. 16). Should he have done more to prepare readers for this discussion? Explain.

- Do you think Wiehe’s concluding statement would have a greater impact if it were in the form of a statement rather than a question? Write a new sentence that could serve as a strong concluding statement for this essay.

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

Do the Benefits of Fracking Outweigh the Environmental Risks?

Education Images/Getty Images

Do the Benefits of Fracking Outweigh the Environmental Risks?

Reread the At Issue box on page 517, which provides background on the question of whether the perceived advantages of fracking outweigh concerns about possible environmental damage. Then, read the sources on the pages that follow.

As you read these sources, you will be asked to respond to some questions and complete some activities. This work is designed to help you understand the content and structure of the selections. When you are finished, you will be ready to decide on the criteria you will use to write an evaluation argument on the topic, “Do the Benefits of Fracking Outweigh the Environmental Risks?”

SOURCES

Elizabeth Kolbert, “Burning Love,” p. 531

Elizabeth Kolbert, “Burning Love,” p. 531 Sean Lennon, “Destroying Precious Land for Gas,” p. 534

Sean Lennon, “Destroying Precious Land for Gas,” p. 534 Thomas L. Friedman, “Get It Right on Gas,” p. 537

Thomas L. Friedman, “Get It Right on Gas,” p. 537 Scott McNally, “Water Contamination—Fracking Is Not the Problem,” p. 540

Scott McNally, “Water Contamination—Fracking Is Not the Problem,” p. 540 Shale Gas Production Subcommittee, From Shale Gas Production Subcommittee 90-Day Report, p. 543

Shale Gas Production Subcommittee, From Shale Gas Production Subcommittee 90-Day Report, p. 543

US Department of Energy USA Today Editorial Board, “Fracking, with Care, Brings Big Benefits,” p. 546

USA Today Editorial Board, “Fracking, with Care, Brings Big Benefits,” p. 546

This article first appeared in the December 5, 2011, issue of the New Yorker.

ELIZABETH KOLBERT

BURNING LOVE

Americans have never met a hydrocarbon they didn’t like. Oil, natural gas, liquefied natural gas, tar-sands oil, coal-bed methane, and coal, which is, mostly, carbon—the country loves them all, not wisely, but too well. To the extent that the United States has an energy policy, it is perhaps best summed up as: if you’ve got it, burn it.1

America’s latest hydrocarbon crush is shale gas. Shale gas has been around for a long time—the Marcellus Shale, which underlies much of Pennsylvania and western New York, dates back to the mid-Devonian period, almost four hundred million years ago—and geologists have been aware of its potential as a fuel source for many decades. But it wasn’t until recently that, owing to advances in drilling technology, extracting the gas became a lucrative proposition. The result has been what National Geographic has called “the great shale gas rush.” In the past ten months alone, some sixteen hundred new wells have been drilled in Pennsylvania; it is projected that the total number in the state could eventually grow to more than a hundred thousand. Nationally, shale-gas production has increased by a factor of twelve in the past ten years.2

Like many rushes before it, the shale-gas version has made some people wealthy and others miserable. Landowners in shale-rich areas have received thousands of dollars an acre in up-front payments for the right to drill under their property, with the promise of thousands more to come in royalties. A new term has been invented to describe them: “shaleionaires.”3

Meanwhile, some of their neighbors—who are, perhaps, also shaleionaires—have watched their tap water turn brown and, on occasion, explode. Shale gas is embedded in dense rock, so drillers use a mixture of water, sand, and chemicals to open up fissures in the stone through which it can escape. (This is the process known as “hydraulic fracturing,” or, more colloquially, “fracking.”) In the 2005 energy bill, largely crafted by Vice-President Dick Cheney, fracking was explicitly exempted from federal review under the Safe Drinking Water Act. As a result of this dispensation, which has been dubbed the Halliburton Loophole, drilling companies are under no obligation to make public which chemicals they use. Likely candidates include such recognized or suspected carcinogens as benzene and formaldehyde.4

Shale gas is found deep underground; most of the Marcellus Shale sits a mile or more beneath the surface, far below the level of groundwater. Industry officials argue that the depth of the formations makes it impossible for fracking to pollute drinking-water supplies. “There have been over a million wells hydraulically fractured in the history of the industry, and there is not one—not one—reported case of a freshwater aquifer having ever been contaminated,” Rex Tillerson, the chairman and C.E.O. of ExxonMobil, declared at a congressional hearing last year.5

Nevertheless, as the Times recently reported, contamination with fracking fluid has occurred. (Details of contamination cases are difficult to get, because most of the records have been sealed in litigation.) And, just a few weeks ago, the Environmental Protection Agency reported that drinking water in Pavillion, Wyoming, contained a chemical that is commonly found in fracking fluid, although the agency has not yet determined whether fracking was the source. The E.P.A. is also investigating several cases of suspected contamination in the town of Dimock, Pennsylvania.6

Shale gas itself presents another potential problem. A recent study by researchers at Duke University showed that methane frequently leaks into drinking water near active fracking sites, which probably explains why some homeowners have been able to set their tap water on fire. Yet another possible source of contamination is so-called “flowback” water. Huge quantities of water are used in fracking, and as much as forty percent of it can come back up out of the gas wells, bringing with it corrosive salts, volatile organic compounds, and radioactive elements, such as radium. Citing public-health concerns, Pennsylvania recently asked drillers to stop taking flowback water to municipal treatment plants.7

New York State currently has a moratorium on fracking permits, pending the adoption of new regulations. Anxiety about New York City’s drinking-water supply has prompted the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation to recommend, in a set of draft rules, that the practice be prohibited in the city’s upstate watershed. (The department is holding a hearing on the proposed regulations this week in Manhattan; a similar hearing, held earlier this month in Binghamton, drew nearly two thousand people.) There is also a moratorium on fracking in the Delaware River Basin, which spans parts of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Pennsylvania and is the source of drinking water for fifteen million people. The Delaware River Basin Commission, the body charged with protecting water quality in the region, was expected to lift that moratorium last week; however, the decision was put off after Delaware’s governor, Jack Markell, a commission member, announced that he would vote against the move. “Once hydrofracturing begins in the basin, the proverbial ‘faucet’ cannot be turned off, with any damage to our freshwater supplies likely requiring generations of effort to clean up,” Markell wrote in a letter explaining his decision.8

Every kind of energy extraction, of course, poses risks. Mountaintop-removal mining, as the name suggests, involves “removing” entire mountaintops, usually with explosives, to get at a layer of coal. Coal plants, meanwhile, produce almost twice the volume of greenhouse gases as natural-gas plants per unit of energy generated. In the end, the best case to be made for fracking is that much of what is already being done is probably even worse.9

“In the end, the best case to be made for fracking is that much of what is already being done is probably even worse.”

The trouble with this sort of argument is that, in the absence of a rational energy policy, there’s no reason to substitute shale gas for coal. We can combust them both! The way things now stand, there’s nothing to prevent us from getting wasted mountains and polluted drinking water, and a ruined climate to boot.10

In the coming decades, ever-improving technologies will almost certainly make new sources of hydrocarbons accessible. At some point, either we will outgrow our infatuation or we will burn our way to a very dark place.11

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

- Kolbert opens her essay with a provocative statement: “Americans have never met a hydrocarbon they didn’t like” (para. 1). Is she attacking her readers? If so, for what purpose?

- In paragraph 3, Kolbert notes that shale-gas drilling “has made some people wealthy and others miserable.” How does she support this statement?

- In presenting background on the development of fracking, Kolbert notes that it was “explicitly exempted from federal review under the Safe Drinking Water Act” (4). What do you see as the significance of this exemption?

- How do you think Kolbert might have expected her readers to react to the following?

“Americans’ latest hydrocarbon crush is shale gas” (2).

“A new term has been invented … ‘shaleionaires’” (3)

“The way things now stand, there’s nothing to prevent us from getting wasted mountains and polluted drinking water, and a ruined climate to boot” (10).

Do these statements exhibit bias on Kolbert’s part? If so, how? If not, explain why the statements are both fair and logical.

- Kolbert takes a strong stand against fracking. Paraphrase her thesis by filling in the following template:

Although it has made many individuals and businesses wealthy, fracking should be banned because ________________________________________.

- Reread Kolbert’s last sentence. Is she committing the either/or fallacy here? Explain.

This op-ed ran in the New York Times on August 27, 2012.

SEAN LENNON

DESTROYING PRECIOUS LAND FOR GAS

On the northern tip of Delaware County, N.Y., where the Catskill Mountains curl up into little kitten hills, and Ouleout Creek slithers north into the Susquehanna River, there is a farm my parents bought before I was born. My earliest memories there are of skipping stones with my father and drinking unpasteurized milk. There are bald eagles and majestic pines, honeybees and raspberries. My mother even planted a ring of white birch trees around the property for protection.1

A few months ago I was asked by a neighbor near our farm to attend a town meeting at the local high school. Some gas companies at the meeting were trying very hard to sell us on a plan to tear through our wilderness and make room for a new pipeline: infrastructure for hydraulic fracturing. Most of the residents at the meeting, many of them organic farmers, were openly defiant. The gas companies didn’t seem to care. They gave us the feeling that whether we liked it or not, they were going to fracture our little town.2

In the late ’70s, when Manhattanites like Andy Warhol and Bianca Jagger were turning Montauk and East Hampton into an epicurean Shangri-La for the Studio 54 crowd, my parents, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, were looking to become amateur dairy farmers. My first introduction to a cow was being taught how to milk it by hand. I’ll never forget the realization that fresh milk could be so much sweeter than what we bought in grocery stores. Although I was rarely able to persuade my schoolmates to leave Long Island for what seemed to them an unreasonably rural escapade, I was lucky enough to experience trout fishing instead of tennis lessons, swimming holes instead of swimming pools, and campfires instead of cable television.3

Though my father died when I was 5, I have always felt lucky to live on land he loved dearly; land in an area that is now on the verge of being destroyed. When the gas companies showed up in our backyard, I felt I needed to do some research. I looked into Pennsylvania, where hundreds of families have been left with ruined drinking water, toxic fumes in the air, industrialized landscapes, thousands of trucks and new roads crosshatching the wilderness, and a devastating and irreversible decline in property value.4

Natural gas has been sold as clean energy. But when the gas comes from fracturing bedrock with about five million gallons of toxic water per well, the word “clean” takes on a disturbingly Orwellian tone. Don’t be fooled. Fracking for shale gas is in truth dirty energy. It inevitably leaks toxic chemicals into the air and water. Industry studies show that 5 percent of wells can leak immediately, and 60 percent over 30 years. There is no such thing as pipes and concrete that won’t eventually break down. It releases a cocktail of chemicals from a menu of more than 600 toxic substances, climate-changing methane, radium, and, of course, uranium.5

“Fracking for shale gas is in truth dirty energy.”

New York is lucky enough to have some of the best drinking water in the world. The well water on my family’s farm comes from the same watersheds that supply all the reservoirs in New York State. That means if our tap water gets dirty, so does New York City’s.6

Gas produced this way is not climate-friendly. Within the first 20 years, methane escaping from within and around the wells, pipelines, and compressor stations is 105 times more powerful a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. With more than a tiny amount of methane leakage, this gas is as bad as coal is for the climate; and since over half the wells leak eventually, it is not a small amount. Even more important, shale gas contains one of the earth’s largest carbon reserves, many times more than our atmosphere can absorb. Burning more than a small fraction of it will render the climate unlivable, raise the price of food, and make coastlines unstable for generations.7

Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, when speaking for “the voices in the sensible center,” seems to think the New York State Association of County Health Officials, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the New York State Nurses Association, and the Medical Society of the State of New York, not to mention Dr. Anthony R. Ingraffea’s studies at Cornell University, are “loud voices at the extremes.” The mayor’s plan to “make sure that the gas is extracted carefully and in the right places” is akin to a smoker telling you, “Smoking lighter cigarettes in the right place at the right time makes it safe to smoke.”8

Few people are aware that America’s Natural Gas Alliance has spent $80 million in a publicity campaign that includes the services of Hill and Knowlton—the public relations firm that through most of the ’50s and ’60s told America that tobacco had no verifiable links to cancer. Natural gas is clean, and cigarettes are healthy—talk about disinformation. To try to counteract this, my mother and I have started a group called Artists Against Fracking.9

My father could have chosen to live anywhere. I suspect he chose to live here because being a New Yorker is not about class, race, or even nationality; it’s about loving New York. Even the United States Geological Survey has said New York’s draft plan fails to protect drinking water supplies, and has also acknowledged the likely link between hydraulic fracturing and recent earthquakes in the Midwest. Surely the voice of the “sensible center” would ask to stop all hydraulic fracturing so that our water, our lives, and our planet could be protected and preserved for generations to come.10

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

- Throughout this essay, Lennon is careful to establish himself as a resident of a rural area, a farmer, and someone who grew up swimming and fishing in an idyllic natural setting. Why does he do this? Does this information appeal to logos, ethos, or pathos? Explain.

- Although Lennon mentions his parents in paragraphs 1 and 2, he doesn’t identify them by name until paragraph 3. Why not? Is his readers’ knowledge of who his parents were likely to add to, detract from, or not affect his credibility on the subject of fracking?

- Why do you think Lennon tells readers in paragraph 4 that he “needed to do some research”? What did his research reveal?

- Reread paragraph 8. Do you think Lennon is making an ad hominem attack on former New York City mayor Michael R. Bloomberg here? Why or why not?

- What kind of evidence does Lennon present to support his position against fracking? Does he include enough evidence—as well as the right kind of evidence—to support his defense of the land he believes is threatened? Why or why not?

The New York Times ran this op-ed on August 4, 2012.

THOMAS L. FRIEDMAN

GET IT RIGHT ON GAS

We are in the midst of a natural gas revolution in America that is a potential game changer for the economy, environment, and our national security—if we do it right.1

The enormous stores of natural gas that have been locked away in shale deposits across America that we’ve now been able to tap into, thanks to breakthroughs in seismic imaging, horizontal drilling, and hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” are enabling us to replace much dirtier coal with cleaner gas as the largest source of electricity generation in America. And natural gas may soon be powering cars, trucks, and ships as well. This is helping to lower our carbon emissions faster than expected and make us more energy secure. And, if prices stay low, it may enable America to bring back manufacturing that migrated overseas. But, as the energy and climate expert Hal Harvey puts it, there is just one big, hugely important question to be asked about this natural gas bounty: “Will it be a transition to a clean energy future, or does it defer a clean energy future?”2

“This is helping to lower our carbon emissions faster than expected and make us more energy secure.”

That is the question—because natural gas is still a fossil fuel. The good news: It emits only half as much greenhouse gas as coal when combusted and, therefore, contributes only half as much to global warming. The better news: The recent glut has made it inexpensive to deploy. But there is a hidden, long-term, cost: A sustained gas glut could undermine new investments in wind, solar, nuclear, and energy efficiency systems—which have zero emissions—and thus keep us addicted to fossil fuels for decades.3

That would be reckless. This year’s global extremes of droughts and floods are totally consistent with models of disruptive, nonlinear climate change. After record warm temperatures in the first half of this year, it was no surprise to find last week that the Department of Agriculture has now designated more than half of all U.S. counties—1, 584 in 32 states—as primary disaster areas where crops and grazing areas have been ravaged by drought.4

That is why on May 29 the British newspaper The Guardian quoted Fatih Birol, the chief economist for the International Energy Agency, as saying that “a golden age for gas is not necessarily a golden age for the climate”—if natural gas ends up sinking renewables. Maria van der Hoeven, executive director of the I.E.A., urged governments to keep in place subsidies and regulations to encourage investments in wind, solar, and other renewables “for years to come” so they remain competitive.5

Moreover, while natural gas is cleaner than coal, extracting it can be very dirty. We have to do this right. For instance, the carbon advantage can be undermined by leakage of uncombusted natural gas from wellheads and pipelines because methane—the primary component of natural gas—is an extremely powerful greenhouse gas, more powerful than carbon dioxide. The big oil companies can easily maintain high drilling standards, but a lot of fracking is done by mom-and-pop drillers that do not. The standards that can make fracking environmentally O.K. are not expensive, but the big drillers want to make sure that the little guys have to apply them, too, so everyone has the same cost basis.6

On July 19, Forbes interviewed George Phydias Mitchell, who, in the 1990s, pioneered the use of fracking to break natural gas free from impermeable shale. According to Forbes, Mitchell argued that fracking needs to be regulated by the Department of Energy, not just states: “Because if they don’t do it right, there could be trouble,” he says. There’s no excuse not to get it right. “There are good techniques to make it safe that should be followed properly,” he says. But, the smaller, independent drillers, “are wild.” “It’s tough to control these independents. If they do something wrong and dangerous, they should punish them.”7

Adds Fred Krupp, the president of the Environmental Defense Fund who has been working with the government and companies on drilling standards: “The economic and national security advantages of natural gas are obvious, but if you tour some of these areas of intensive development the environmental impacts are equally obvious.” We need nationally accepted standards for controlling methane leakage, for controlling water used in fracking—where you get it, how you treat the polluted water that comes out from the fracking process, and how you protect aquifers—and for ensuring that communities have the right to say no to drilling. “The key message,” said Krupp, “is you gotta get the rules right. States need real inspector capacity and compliance schemes where companies certify they have done it right and there are severe penalties if they perjure.”8

Energy companies who want to keep regulations lax need to understand that a series of mishaps around natural gas will—justifiably—trigger an environmental backlash to stop it.9

But we also need to get the economics right. We’ll need more tax revenue to reach a budget deal in January. Why not a carbon tax that raises enough money to help pay down the deficit and lower both personal income taxes and corporate taxes—and ensures that renewables remain competitive with natural gas? That would ensure this gas revolution transforms America, not just our electric grid.10

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

- Friedman uses the terms revolution and game changer in his opening paragraph. Is this language appropriate here, or do you think Friedman is exaggerating or overstating his case?

- Friedman does not consider fracking to be evil, nor does he see it as a solution to all of America’s energy problems; his position falls somewhere in between these two extremes. State Friedman’s position in one sentence. Assuming that this sentence could serve as the essay’s thesis statement, where would you locate it? Why?

- What experts does Friedman quote? Do they agree with one another, or do they have different views of fracking? Do they all agree with Friedman? Explain.

- What criteria does Friedman use to evaluate fracking? Are these the same criteria used by other writers whose essays appear in this section?

- According to Friedman, how should the United States “get it right on gas”? What “right” steps does he propose? Do you agree?

Scientific American published this argument as a guest post on its blog on January 25, 2012.

SCOTT MCNALLY

WATER CONTAMINATION — FRACKING IS NOT THE PROBLEM

With the current negative attention and controversy surrounding shale gas drilling, the words hydraulic fracturing or fracking have become synonymous with something else: water contamination. But according to recent research out of MIT, the contamination of drinking water near natural gas wells is caused by something totally different. In fact, fracking has nothing to do with it.1

Shale gas was long considered inaccessible and unprofitable because of the low permeability of shale formations, but recent developments in horizontal drilling and multi-stage hydraulic fracturing have made shale gas production economically viable. As a result, shale gas drilling has increased dramatically and sparked debates on the safety and environmental impacts of hydraulic fracturing.2

You may have seen the commercials supporting fracking that say, “clean burning natural gas is the gateway to our low carbon future.” You may have also seen the Academy Award Nominated documentary Gasland, which highlights some of the environmental risks and discusses contaminated aquifers. Some have even called for a ban on fracking. Unfortunately, in this debate, some of the facts have been clouded by misinformation, anecdotal evidence, and back and forth attempts to discredit those on both side of the argument.3

So what is the truth?4

Can drilling for natural gas contaminate drinking water? Yes.5

Is hydraulic fracturing to blame? No.6

Bottom line: water contamination does happen, but not because of hydraulic fracturing. The MIT Future of Natural Gas Study, released in June 2011, examines the causes of 43 reported environmental incidents and finds that, “no incidents of direct invasion of shallow water zones by fracture fluids during the fracturing process have been recorded.”7

“Bottom line: water contamination does happen, but not because of hydraulic fracturing.”

So what causes the contamination? According to the study, “almost 50 percent [of the incidents were] the result of drilling operations … most frequently related to inadequate cementing of casing into wellbores.” The table below is from the Future of Natural Gas Study and highlights the frequency and causes of incidents.8

| Type of incident | Number Reported | Percentage of Total |

| Groundwater contamination by natural gas | 20 | 47% |

| On-site surface spills | 14 | 33% |

| Off-site disposal issues | 4 | 9% |

| Water withdrawal issues | 2 | 4% |

| Air quality | 1 | 2% |

| Blowouts | 2 | 4% |

While the most common incident is groundwater contamination resulting from drilling operations, the study also states that, “Properly implemented cementing procedures should prevent this from occurring.”9

But, to be absolutely clear, hydraulic fracturing is not part of the drilling process. It is part of well completions, and is typically done several weeks after drilling has stopped. This is where much of the confusion sets in. You may have heard something like this before: “There has never been a documented case of the fractures in a shale gas production zone migrating upward to the water bearing zones. There are thousands of feet of impermeable rock separating the two, and the rock mechanics make it a physical impossibility.”10

That is true. However, that does not mean fracking fluid cannot get into the aquifer. So how does this happen? If fractures never reach the aquifers, then how does the fracking fluid get there?11

It goes like this:12

Sometimes, drillers have to drill through an aquifer to access a natural gas zone that is farther below. (By the way, an aquifer is an underground layer of water-bearing permeable rock. It is not an underground lake or cavern that is filled with water, like many people imagine.) If the act of drilling through the aquifer and cementing the walls of the hole is not done carefully, there is a higher chance that the cement casing can crack, leaking hydrocarbons and other fluids into the aquifer. If there is a casing leak near the water table, whatever is traveling up or down the well can leak into the aquifer. Since the fracking fluids have to travel through this pipe twice (once on the way down, once on the way back up), it can contaminate the water through the casing leak. In fact, whatever travels through that pipe can leak into the aquifer. Sometimes it is fracking fluid, but more commonly, it is methane, drilling mud, or produced formation water.13

Aquifer contamination can happen whether you frac a well or not, and bad cementing and casing leaks are possible in any well—vertical, horizontal, fracked, or unfracked.14

Now, there are significant environmental concerns related to gas drilling, but let’s put them into context. 20,000 shale gas wells have been fracked in the last ten years, and the Future of Natural Gas Study pulled 43 of the most widely reported environmental incidents, and not a single one was caused by fracking. Now, there were likely more than just 43 environmental incidents, indeed, the study mentions, “The data set does not purport to be comprehensive, but is intended to give a sense of the relative frequency of various types of incidents.”15

Regardless of the frequency of incidents, any spill or leak is unacceptable, and the pressure should be on the drillers and operators to minimize the environmental impacts of natural gas production. But, the data show the vast majority of natural gas development projects are safe, and the existing environmental concerns are largely preventable.16

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

- In your own words, restate McNally’s position on the relationship between fracking and water contamination. If, as his title states, “fracking is not the problem,” what is the problem?

- In paragraph 3, McNally refers to pro-fracking commercials and to the documentary Gasland. Why? What does he hope to accomplish?

- In paragraph 7, McNally supports his position by summarizing the results of an MIT study. Does he provide additional support? If so, what kind and where? Do you think he provides enough support?

- Evaluate the table presented in paragraph 8. Is it helpful? Is it necessary? Explain your reasoning.

- In paragraph 15, McNally acknowledges that there are “significant environmental concerns related to gas drilling.” Does this statement undercut his argument? Why or why not?

The material below first appeared in a report by the Shale Gas Production Subcommittee for the U.S. Department of Energy in 2011.

FROM SHALE GAS PRODUCTION SUBCOMMITTEE 90-DAY REPORT

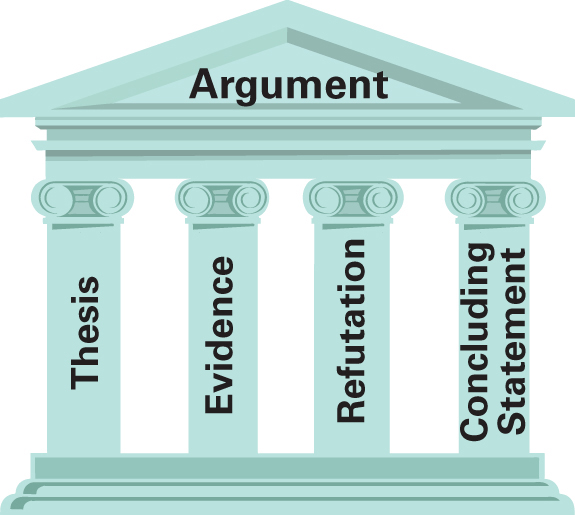

The Subcommittee believes that the U.S. shale gas resource has enormous potential to provide economic and environmental benefits for the county. Shale gas is a widely distributed resource in North America that can be relatively cheaply produced, creating jobs across the country. Natural gas—if properly produced and transported—also offers climate change advantages because of its low carbon content compared to coal.1

Education Images/Getty Images

From Shale Gas Production Subcommittee 90-Day Report

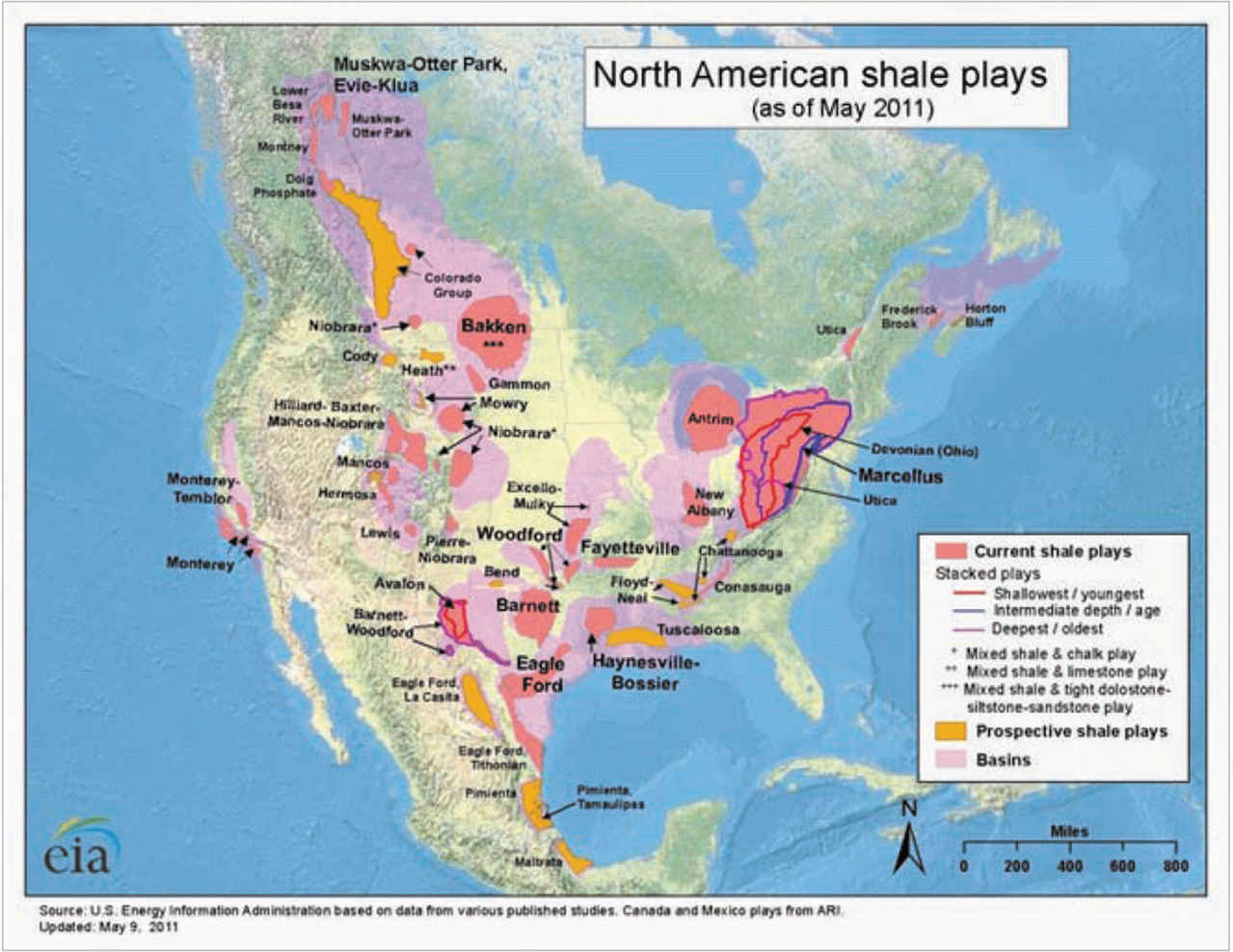

1. Current shale plays: In the north-east region of the USA, it is located in the area of Utica, Frederick Brook, Horton Bluff, Antrim, Devonian (Ohio), Marcellus, and Utica, along with New Albany. In the south-east region of Haynesville-Bossier, Eagle Ford, Barnett, Woodford, Avalon, and Excello-Mulky. In the central west region of Bakken, Gammon, Mowry, Niobrara, Mancos, Niobrara, Pierre Niobrara, Avalon, and Monteray on the western coast, Lower Besa River, Montory, and Muskwa-Otter Park in the North-western region.(i) Shallowest/youngest stacked plays: Region around Utica in the east, and Avalon in mid-south.(ii) Intermediate depth/age stacked plays: Region around Devonian (Ohio), Marcellus, and Utica in the east.(iii) Deepest/oldest stacked plays: Region lying between Muskwa-Otter Park in the west to Bakken in the center, and all the way down to Lewis, covering the regions of Gammon, Mowry, Niobrara, and Heath. It also covers the western coastal area of Monterey-Temblor. In the south-east, it covers the region around Woodford, Eagle Ford, Haynesville-Bossier, and New Albany.(iv) Mixed Shale and Chalk play: Haynesville Bossier, Niobrara near Mowry, Monterey, and Niobrara near Bakken.(v) Mixed shale and limestone play: Heath.(vi) Mixed shale and tight dolostone-siltstone-sandstone play: Bakken.2. Prospective shale plays: Region lying between Haynesville Bossier, and Tuscaloosa, region lying between Eagle Ford La Casalta, and Eagle Ford Tithonian, and the region lying between Doig Phosphate, and Colorado Group, Cody, Heath, and Chattanooga.3. Basins: Region lying around Muskwa Otter Park, Colorado Group, Gammon, Mowry, Niobrara, Monterey Temblor, Barnett Woodford, Eagle Ford, Haynesville Bossier, Woodford, Excello-Mulky, Floyd Neal, Tuscaloosa, Chattnooga, Conasauga, and New Albany.

Domestic production of shale gas also has the potential over time to reduce dependence on imported oil for the United States. International shale gas production will increase the diversity of supply for other nations. Both these developments offer important national security benefits.12

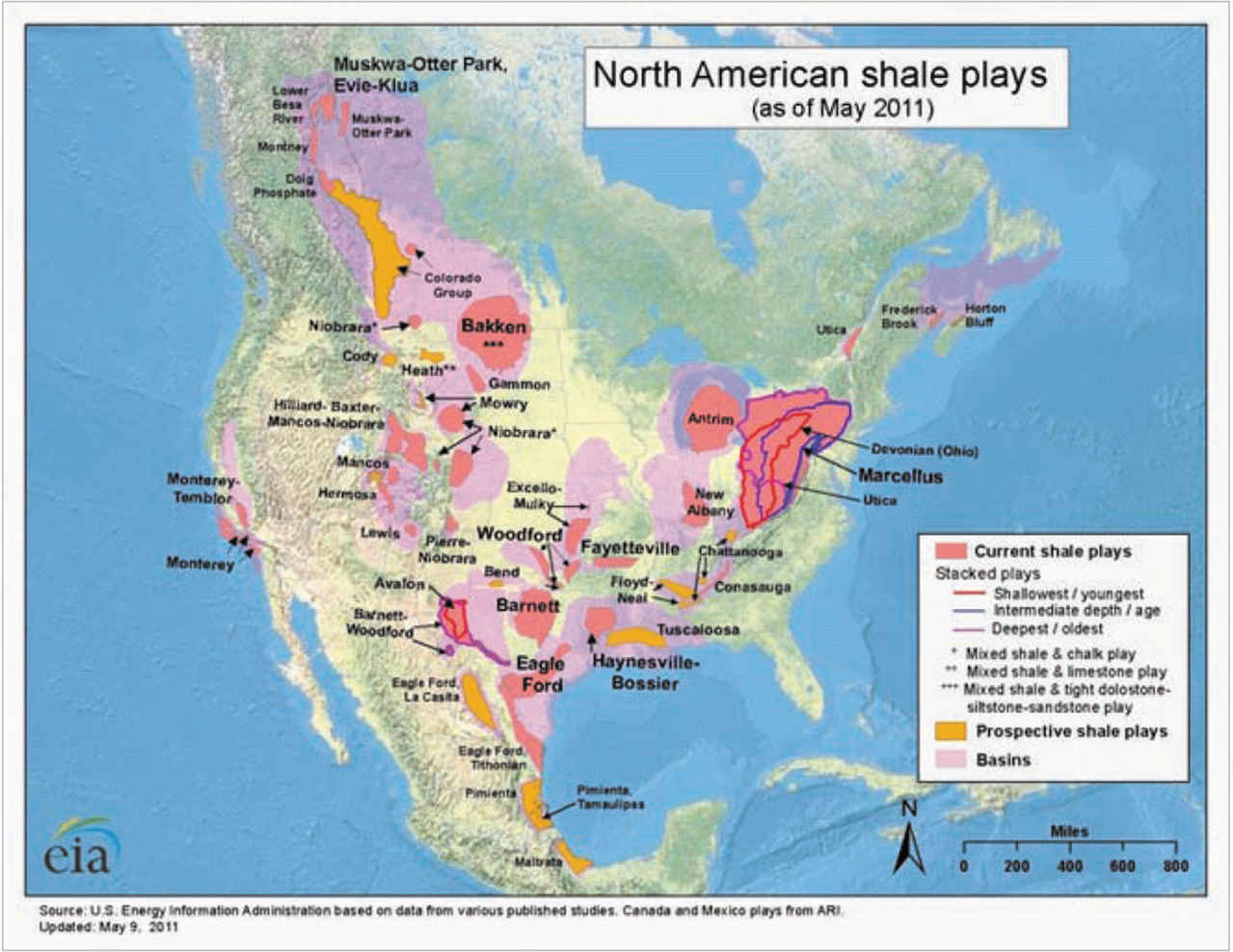

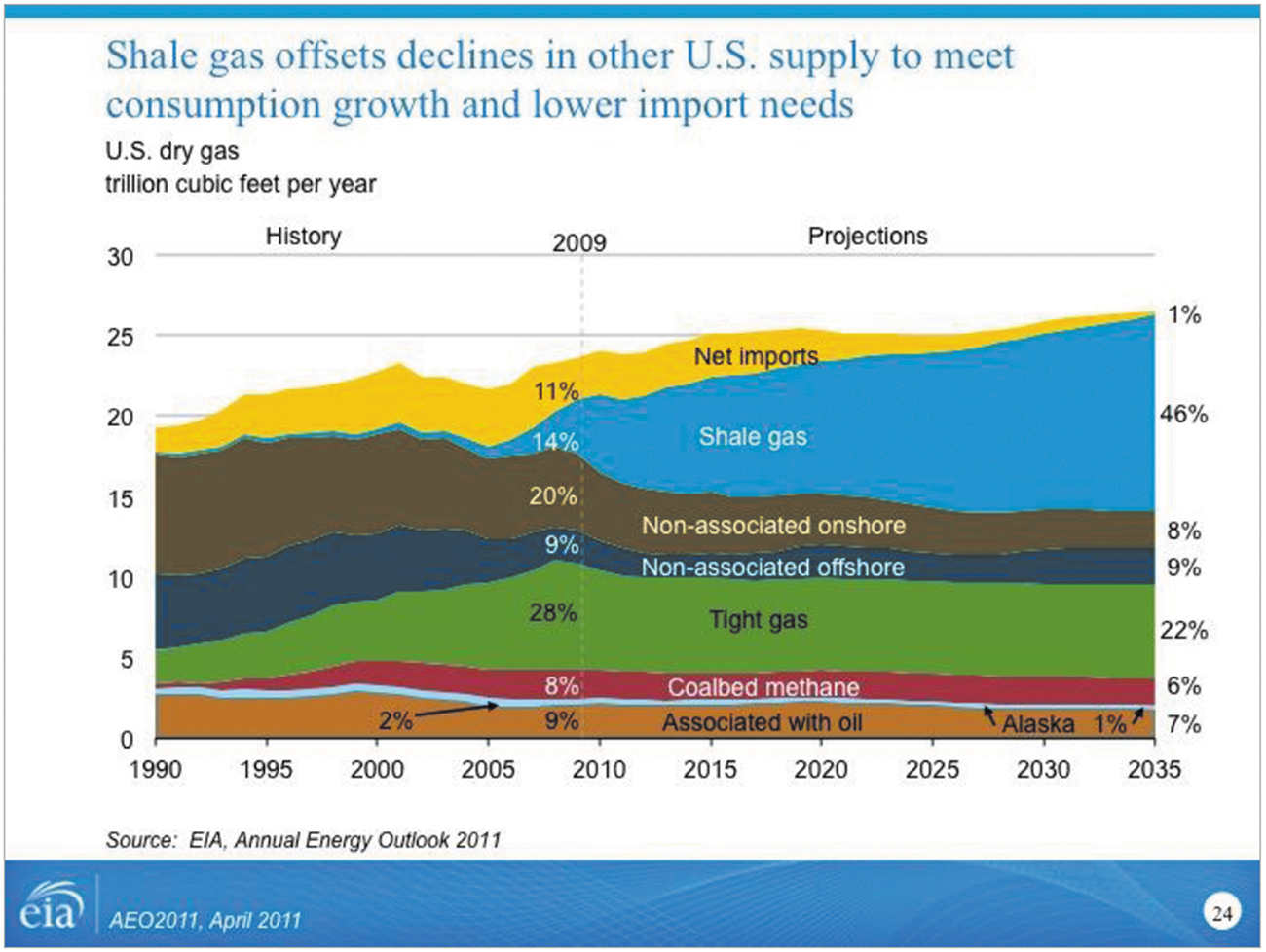

The development of shale gas in the United States has been very rapid. Natural gas from all sources is one of America’s major fuels, providing about 25 percent of total U.S. energy. Shale gas, in turn, was less than 2 percent of total U.S. natural gas production in 2001. Today, it is approaching 30 percent.2 But it was only around 2008 that the significance of shale gas began to be widely recognized. Since then, output has increased four-fold. It has brought new regions into the supply mix. Output from the Haynesville shale, mostly in Louisiana, for example, was negligible in 2008; today, the Haynesville shale alone produces 8 percent of total U.S. natural gas output. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the rapid expansion of shale gas production is expected to continue in the future. The EIA projects shale gas to be 46 percent of domestic production by 2035. The following figure shows the stunning change.3

US Department of Energy

US Department of Energy

Image shows a topographical map with "year" on the X-axis, U.S. dry gas in trillion cubic feet per year in the range of 0 to 30 on the left Y-axis, and their percentage on the right hand side Y-axis. This map shows 2009 as the dividing year between 1990 to 2009, shown as History, and the time period starting from 2009, and ending at the year 2035, shown as Projections. The various levels shown in the map are, starting from base and moving up: 1. Base shows association with consumption of oil, which was around 9 percent in the year 2009. Though, its share in total dry gas consumption was much higher at about 4 trillion cubic feet per year during 1990-2009, its share is likely to fall to around 7 percent of the total gas consumption in the U.S. by the year 2035.2. Above it, is the contribution of Alaska in total dry gas consumption in U.S., which was around 2 percent in the year 2009, and likely to fall to 1 percent of the total consumption by the year 2035. 3. Above it, is the share of Coalbed methane, with its share at 8 percent in the year 2009, and likely to reduce to 6 percent by the year 2035. 4. Above it, is the share of Tight gas, with its production at about 7.5 trillion cubic feet per year, and stood at 28 percent in the year 2009, but is projected to reduce to 22 percent by the year 2035. 5. Above it, is the share of Non-associated offshore, which stood at 4 trillion cubic feet per year in terms of consumption. Its share was 9 percent in 2009 in total consumption to U.S., which is likely to remain constant at 9 percent only.6. Above it, is the share of Non-associated onshore, with its share in total consumption at around 8 trillion cubic feet per year. Its share was at 20 percent in the year 2009, and is projected to be around 8 percent in the year 2035.7. Above it, is the share of Shale gas, which had almost nil consumption share during 1990 to 2009. Its share stood at 14 percent in the year 2009, and its share is expected to increase to 46 percent by the year 2035.8. The top most layer shows net imports, with their production at around 2 trillion cubic feet per year in 1990. Its share increased to 11 percent in 2009, and is likely to decrease to 1 percent by the year 2035.

The economic significance is potentially very large. While estimates vary, well over 200,000 jobs (direct, indirect, and induced) have been created over the last several years by the development of domestic production of shale gas, and tens of thousands more will be created in the future.3 As late as 2007, before the impact of the shale gas revolution, it was assumed that the United States would be importing large amounts of liquefied natural gas from the Middle East and other areas. Today, the United States is essentially self-sufficient in natural gas, with the only notable imports being from Canada, and expected to remain so for many decades. The price of natural gas has fallen by more than a factor of two since 2008, benefiting consumers in the lower cost of home heating and electricity.4

Endnotes

1 The James Baker III Institute for Public Policy at Rice University has recently released a report on Shale Gas and U.S. National Security, available at: http://bakerinstitute.org/publications/EFpub-DOEShaleGas-07192011.pdf.

2 As a share of total dry gas production in the “lower 48,” shale gas was 6 percent in 2006, 8 percent in 2007, at which time its share began to grow rapidly—reaching 12 percent in 2008, 16 percent in 2009, and 24 percent in 2010. In June 2011, it reached 29 percent. Source: Energy Information Administration and Lippman Consulting.

3 Timothy Considine, Robert W. Watson, and Nicholas B. Considine, “The Economy Opportunities of Shale Energy Development,” Manhattan Institute, May 2011, Table 2, page 6.

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

- What position on fracking is taken by the authors of this report?

- Do the visuals simply present information, or do they actually make an argument? Explain your reasoning.

- This report was produced by a subcommittee for the U.S. Department of Energy. How do you think the affiliation of these writers might have influenced their ethos? How does their affiliation affect your response to the report?

This editorial was posted on July 5, 2015, at USAToday.com.

USA TODAY EDITORIAL BOARD

FRACKING, WITH CARE, BRINGS BIG BENEFITS

Fracking—the practice of cracking open underground oil and gas formations with water, sand, and chemicals—has rescued U.S. energy production from a dangerous decline. Any debate about banning it should take a hard look at what that would cost the nation and at facts that aren’t always part of the discussion.1

Those facts are spelled out in a recent report from the Environmental Protection Agency on fracking and groundwater. One of the harshest charges against fracking, often leveled with apocalyptic intensity by its foes, is that it indiscriminately contaminates vital drinking water supplies.2

The EPA’s timely report essentially said that’s overblown.3

The study identified many ways fracking could cause damage, but found little evidence that it had. Yes, there were instances of contaminated drinking water wells, but there was no evidence of “widespread, systemic” harm, and the number of problems that did occur “was small compared to the number of (fracked) wells.”4

“The study identified many ways fracking could cause damage, but found little evidence that it had.”

Presuming no follow-up investigations change these findings, the report adds to the solid case that fracking should continue, with careful oversight, and that bans in Maryland, New York, and other states are wrongheaded.5

The EPA findings come as welcome news because it’s hard to overstate the impact fracking has had on U.S. oil and gas production, which looked to be in irreversible decline in the 1980s. The decline raised fears that imports would soar, making the United States even more dependent than it already was on other nations.6

Fracking now accounts for 56 percent of U.S. natural gas production and 48 percent of oil output, according to the Energy Information Administration. The boom has helped make America the world’s No. 1 producer of oil and gas, and it has pushed the nation much closer to energy independence than almost anyone dared hope in the 1980s and 1990s.7

Huge new natural gas supplies have helped lower prices, fuel a manufacturing turnaround, and displace much dirtier coal in electricity production, cutting air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.8

All that said, the EPA report does validate fears that fracking can be a serious hazard if done sloppily. Like conventional wells, fracked wells have to pass through groundwater on their way to oil and gas zones that can be a mile or more below the deepest groundwater. Wells must be secured with casing and cement that keep fracking fluids, oil, and gas from escaping into drinking water, but the EPA found scattered instances where inadequate casing or a bad cement job allowed natural gas and chemicals to get into groundwater.9

Drilling for oil and gas is complicated and challenging, but safe drilling and production practices have been known for decades. Drillers have learned that the price for sloppiness can be catastrophic, as with the Deepwater Horizon blowout in the Gulf of Mexico five years ago, which just cost BP a settlement for nearly $19 billion.10

Ultimately, it’s up to the industry to show that the considerable rewards from fracking justify the sort of risks the EPA study identified. So far, that’s what has happened.11

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR WRITING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR WRITING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

- This newspaper editorial begins with a definition of fracking. Is this an effective opening strategy? Why or why not?

- The writers of this editorial take a stand against banning fracking, citing its benefits. What are those benefits? Do you agree with their position?

- Where do the writers summarize arguments in favor of banning fracking? What are these arguments? Do the writers effectively refute them? Explain.

- According to the writers, under what circumstances can fracking pose dangers? How might these dangers be minimized or eliminated?

- What do the writers mean by “apocalyptic intensity” (para. 2)? What does their use of this phrase tell you about their view of those who are against fracking? Can you identify any other language that supports the writers’ view of the anti-fracking community?

- Do you find the editorial’s brief conclusion to be sufficiently strong, or do you think the writers need to do more? Explain.

TEMPLATE FOR WRITING AN EVALUATION ARGUMENT

Write a one-paragraph evaluation argument in which you take a position on whether the benefits of fracking are worth the environmental risks. Follow the template below, filling in the blanks to create your argument.

Depending on the criteria used for evaluation, fracking can be seen in a largely positive or negative light. If it is judged on the basis of ______________________________________, it seems clear that it (is / is not) a valuable and necessary process. Some people say that _______________________________. They also point out that ___________________________________________. Others disagree with this position, claiming that _______________________________________________________. However, _____________________________________________________________________________________________. All things considered, __________________________________________________________________________.

EXERCISE 14.6

EXERCISE 14.6

In a group of three or four students, discuss your own opinions about the pros and cons of fracking. Is fracking really necessary? What benefits are associated with this process? What alternative scenarios are possible? What possible negative outcomes do you see? Write a paragraph that summarizes your group’s conclusions.

EXERCISE 14.7

EXERCISE 14.7

Write an evaluation argument on the topic, “Do the Benefits of Fracking Outweigh the Environmental Risks?” Begin by establishing the criteria by which you will evaluate both benefits and risks. Then, consider how well fracking meets these criteria. (If you like, you may incorporate the material you developed in the template and Exercise 14.6 into your essay.) Cite the sources on pages 531–547, and be sure to document the sources you use and to include a works-cited page. (See Chapter 10 for information on documenting sources.)

EXERCISE 14.8

EXERCISE 14.8

Review the four pillars of argument discussed in Chapter 1. Does your essay include all four elements of an effective argument? Add anything that is missing. Then, label the key elements of your essay.

WRITING ASSIGNMENTS: EVALUATION ARGUMENTS

WRITING ASSIGNMENTS: EVALUATION ARGUMENTS

- As a college student, you have probably had to fill out courseevaluation forms. Now, you are going to write an evaluation of one of your courses in the form of an argumentative essay that takes a strong stand on the quality of the course. Before you begin, decide on the criteria by which you will evaluate it—for example, what practical skills it provided to prepare you for your future courses or employment, whether you enjoyed the course, or what you learned. (If you can download an evaluation form, you can use it to help you brainstorm.)

- Write an evaluation argument challenging a popular position on the quality of a product or service that you know or use. For example, you can defend a campus service that most students criticize or criticize a popular restaurant or film. Be sure you establish your criteria for evaluation before you begin. (You do not have to use the same criteria used by those who have taken the opposite position.)

- Write a comparative evaluation—an essay in which you argue that one thing is superior to another. You can compare two websites, two streaming services, two part-time jobs, or any other two subjects you feel confident you can write about. In your thesis, take the position that one of your two subjects is superior to the other. As you would with any evaluation, begin by deciding on the criteria you will use.