Structuring a Cause-and-Effect Argument

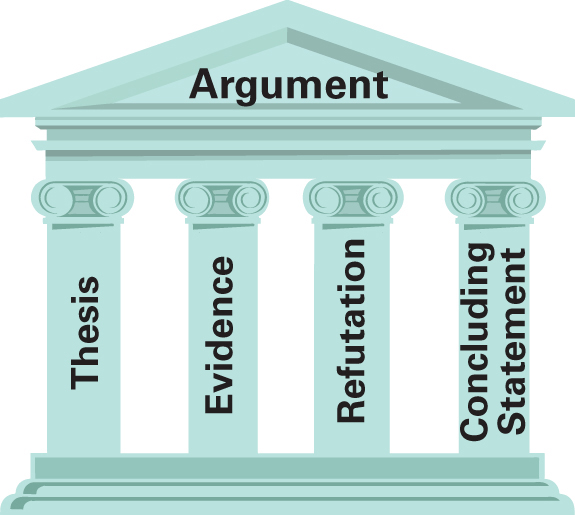

Generally speaking, a cause-and-effect argument can be structured in the following way:

Introduction: Establishes a context for the argument by explaining the need to examine causes or to consider effects; states the essay’s thesis

Evidence (first point in support of thesis): Discusses less important causes or effects

Evidence (second point in support of thesis): Discusses major causes or effects

Refutation of opposing arguments: Considers and rejects other possible causes or effects

Conclusion: Reinforces the argument’s main point; includes a strong concluding statement

Other organizational patterns are also possible. For example, you might decide to refute opposing arguments before you have discussed arguments in support of your thesis. You might also include a background paragraph (as the student writer whose essay begins below does). Finally, you might decide to organize your essay as a causal chain (see pp. 472–473).

![]() The following student essay illustrates one possible structure for a cause-and-effect argument. (Note, for example, that the refutation of opposing arguments precedes the evidence.) The student writer argues that, contrary to popular opinion, texting is not causing damage to the English language but is a creative force with the power to enrich and expand the language.

The following student essay illustrates one possible structure for a cause-and-effect argument. (Note, for example, that the refutation of opposing arguments precedes the evidence.) The student writer argues that, contrary to popular opinion, texting is not causing damage to the English language but is a creative force with the power to enrich and expand the language.

GRAMMAR IN CONTEXT

Avoiding “The Reason Is Because”

When you write a cause-and-effect argument, you connect causes to effects. In the process, you might be tempted to use the ungrammatical phrase the reason is because. However, the word because means “for the reason that”; therefore, it is redundant to say “the reason is because” (which actually means “the reason is for the reason that”). Instead, use the grammatical phrase “the reason is that.”

| Incorrect | Another reason texting is so valuable is because it encourages creative use of language. |

| Correct | Another reason texting is so valuable is that it encourages creative use of language. |

EXERCISE 13.7

EXERCISE 13.7

The following essay, “Should the World of Toys Be Gender-Free?” by Peggy Orenstein, is a cause-and-effect argument. Read the essay carefully, and then answer the questions that follow it, consulting the outline on pages 475–476 if necessary.

This opinion column is from the December 29, 2011, New York Times.

PEGGY ORENSTEIN

SHOULD THE WORLD OF TOYS BE GENDER-FREE?

Now that the wrapping paper and the infernal clamshell packaging have been relegated to the curb and the paying off of holiday bills has begun, the toy industry is gearing up—for Christmas 2012. And its early offerings have ignited a new debate over nature, nurture, toys, and sex.1

Hamleys, which is London’s 251-year-old version of F.A.O. Schwarz, recently dismantled its pink “girls” and blue “boys” sections in favor of a gender-neutral store with red-and-white signage. Rather than floors dedicated to Barbie dolls and action figures, merchandise is now organized by types (Soft Toys) and interests (Outdoor).2

That free-to-be gesture was offset by Lego, whose Friends collection, aimed at girls, will hit stores this month with the goal of becoming a holiday must-have by the fall. Set in fictive Heartlake City (and supported by a $40 million marketing campaign), the line features new, pastel-colored blocks that allow a budding Kardashian, among other things, to build herself a cafe or a beauty salon. Its tasty-sounding “ladyfig” characters are also taller and curvier than the typical Legoland denizen.3

“Should gender be systematically expunged from playthings?”

So who has it right? Should gender be systematically expunged from playthings? Or is Lego merely being realistic, earnestly meeting girls halfway in an attempt to stoke their interest in engineering?4

Among the “10 characteristics for Lego” described in 1963 by a son of the founder was that it was “for girls and for boys,” as Bloomberg Businessweek reported. But the new Friends collection, Lego says, was based on months of anthropological research revealing that—gasp!—the sexes play differently.5

While as toddlers they interact similarly with the company’s Duplo blocks, by preschool girls prefer playthings that are pretty, exude “harmony,” and allow them to tell a story. They may enjoy building, but they favor role play. So it’s bye-bye Bionicles, hello princesses. In order to be gender-fair, today’s executives insist, they have to be gender-specific.6

As any developmental psychologist will tell you, those observations are, to a degree, correct. Toy choice among young children is the Big Kahuna of sex differences, one of the largest across the life span. It transcends not only culture but species: in two separate studies of primates, in 2002 and 2008, researchers found that males gravitated toward stereotypically masculine toys (like cars and balls) while females went ape for dolls. Both sexes, incidentally, appreciated stuffed animals and books.7

Human boys and girls not only tend to play differently from one another—with girls typically clustering in pairs or trios, chatting together more than boys, and playing more cooperatively—but, when given a choice, usually prefer hanging with their own kind.8

Score one for Lego, right? Not so fast. Preschoolers may be the self-appointed chiefs of the gender police, eager to enforce and embrace the most rigid views. Yet, according to Lise Eliot, a neuroscientist and the author of Pink Brain, Blue Brain, that’s also the age when their brains are most malleable, most open to influence on the abilities and roles that traditionally go with their sex.9

Every experience, every interaction, every activity—when they laugh, cry, learn, play—strengthens some neural circuits at the expense of others, and the younger the child the greater the effect. Consider: boys from more egalitarian homes are more nurturing toward babies. Meanwhile, in a study of more than 5,000 3-year-olds, girls with older brothers had stronger spatial skills than both girls and boys with older sisters.10

At issue, then, is not nature or nurture but how nurture becomes nature: the environment in which children play and grow can encourage a range of aptitudes or foreclose them. So blithely indulging—let alone exploiting—stereotypically gendered play patterns may have a more negative long-term impact on kids’ potential than parents imagine. And promoting, without forcing, cross-sex friendships as well as a breadth of play styles may be more beneficial. There is even evidence that children who have opposite-sex friendships during their early years have healthier romantic relationships as teenagers.11

Traditionally, toys were intended to communicate parental values and expectations, to train children for their future adult roles. Today’s boys and girls will eventually be one another’s professional peers, employers, employees, romantic partners, co-parents. How can they develop skills for such collaborations from toys that increasingly emphasize, reinforce, or even create, gender differences? What do girls learn about who they should be from Lego kits with beauty parlors or the flood of “girl friendly” science kits that run the gamut from “beauty spa lab” to “perfume factory”?12

The rebellion against such gender apartheid may have begun. Consider the latest cute-kid video to go viral on YouTube: “Riley on Marketing” shows a little girl in front of a wall of pink packaging, asking, “Why do all the girls have to buy pink stuff and all the boys have to buy different-color stuff?” It has been viewed more than 2.4 million times.13

Perhaps, then, Hamleys is on to something, though it will doubtless meet with resistance—even rejection—from both its pint-size customers and multinational vendors. As for me, I’m trying to track down a poster of a 1981 ad for a Lego “universal” building set to give to my daughter. In it, a freckle-faced girl with copper-colored braids, baggy jeans, a T-shirt, and sneakers proudly holds out a jumbly, multi-hued Lego creation. Beneath it, a tag line reads, “What it is is beautiful.”14

Identifying the Elements of a Cause-and-Effect Argument

- Where does Orenstein answer the question her title asks? How would you answer this question?

- Orenstein’s discussion of toys is based on the assumption that the world would be a better place if children were raised in a gender-neutral environment, but she does not offer any evidence to support this implied idea. Should she have? Is she begging the question?

- In paragraph 7, Orenstein reports on two studies of primates. What conclusion does this evidence support? What conclusion does Lise Eliot’s research (para. 9) support?

- In paragraph 7, Orenstein reports on two studies of primates. What conclusion does this evidence support? What conclusion does Lise Eliot’s research (para. 9) support?How do you react to Orenstein’s use of the term gender apartheid (13)? What does this term mean? What connotations does it have? Given these connotations, do you think her use of this term is appropriate? Why or why not?

- According to Orenstein, what effects do stereotyped toys have on children? Does she support her claims?

- Orenstein’s thesis seems to leave no room for compromise. Given the possibility that some of her readers might disagree with her, should she have softened her position? What compromise position might she have proposed?

- This essay traces a causal chain. The first link in this chain is the “anthropological research revealing that … the sexes play differently” (5). Complete the causal chain by filling in the template below.

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

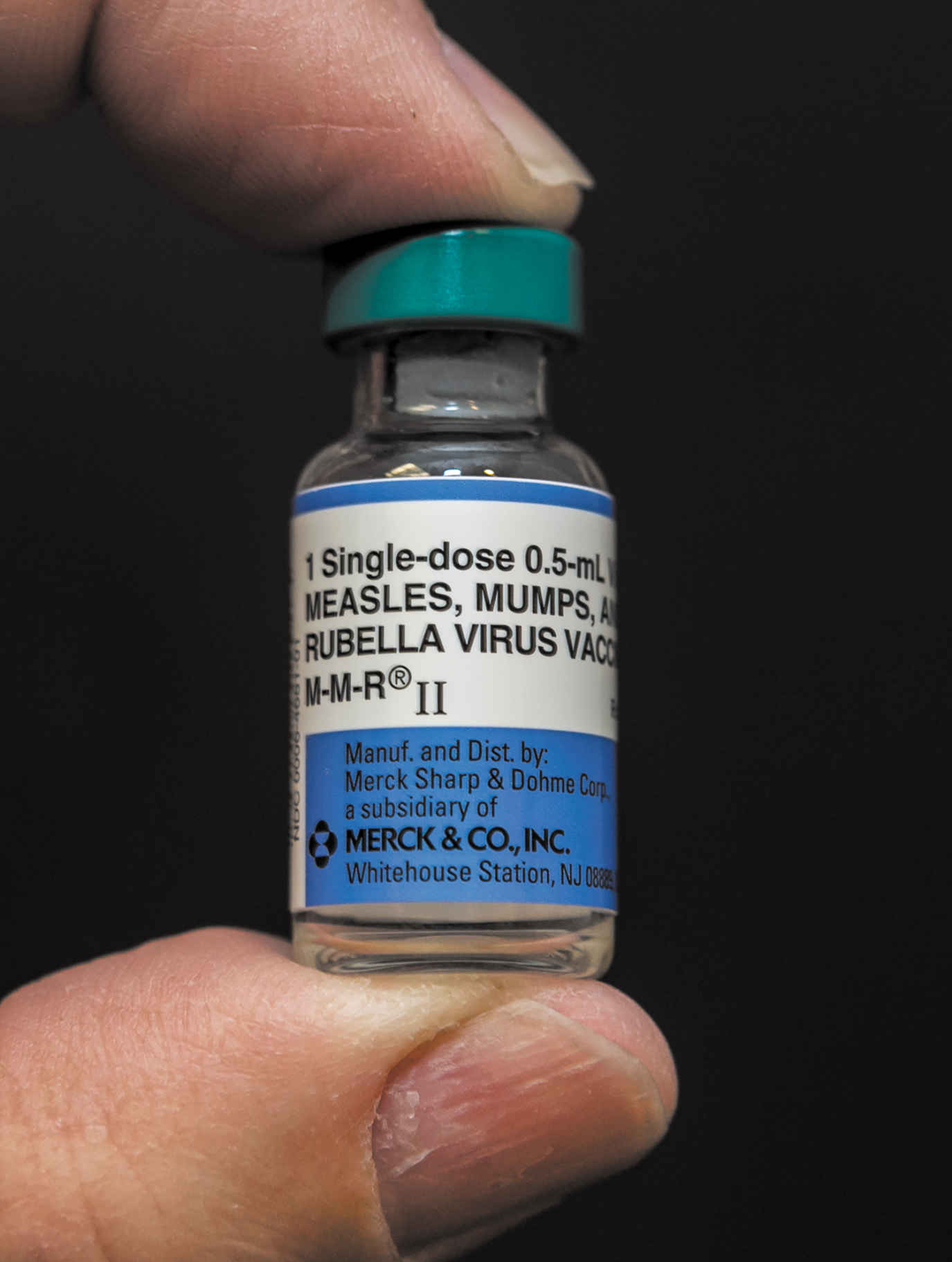

Should Vaccination Be Required for All Children?

AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes

Should Vaccination Be Required for All Children?

Reread the At Issue box on pages 467– 468. Then, read the sources on the pages that follow.

As you read each of these sources, you will be asked to respond to a series of questions and complete some simple activities. This work will help you to understand the content and structure of the material you read. When you are finished, you will be prepared to write a cause-and-effect argument in which you take a position on the topic, “Should Vaccination Be Required for All Children?”

SOURCES

Clyde Haberman, “A Discredited Vaccine Study’s Continuing Impact on Public Health,” p. 483

Clyde Haberman, “A Discredited Vaccine Study’s Continuing Impact on Public Health,” p. 483 Janet D. Stemwedel, “Saying No to Vaccines,” p. 486

Janet D. Stemwedel, “Saying No to Vaccines,” p. 486 Mahesh Vidula, “Individual Rights vs. Public Health: The Vaccination Debate,” p. 491

Mahesh Vidula, “Individual Rights vs. Public Health: The Vaccination Debate,” p. 491 Ben Carson, “Vaccinations Are for the Good of the Nation,” p. 502

Ben Carson, “Vaccinations Are for the Good of the Nation,” p. 502 Russell Saunders, “Pediatrician: Vaccinate Your Kids—or Get Out of My Office,” p. 504

Russell Saunders, “Pediatrician: Vaccinate Your Kids—or Get Out of My Office,” p. 504 Jeffrey Singer, “Vaccination and Free Will,” p. 507

Jeffrey Singer, “Vaccination and Free Will,” p. 507 Jenny McCarthy, “The Gray Area on Vaccines,” p. 510

Jenny McCarthy, “The Gray Area on Vaccines,” p. 510 “Facts about the Measles” (graphics), p. 512

“Facts about the Measles” (graphics), p. 512

This story first appeared in the New York Times on February 1, 2015.

CLYDE HABERMAN

A DISCREDITED VACCINE STUDY’S CONTINUING IMPACT ON PUBLIC HEALTH

In the churning over the refusal of some parents to immunize their children against certain diseases, a venerable Latin phrase may prove useful: Post hoc, ergo propter hoc. It means, “After this, therefore because of this.” In plainer language: Event B follows Event A, so B must be the direct result of A. It is a classic fallacy in logic.1

It is also a trap into which many Americans have fallen. That is the consensus among health professionals trying to contain recent spurts of infectious diseases that they had believed were forever in the country’s rearview mirror. They worry that too many people are not getting their children vaccinated, out of a conviction that inoculations are risky.2

Some parents feel certain that vaccines can lead to autism, if only because there have been instances when a child got a shot and then became autistic. Post hoc, ergo propter hoc. Making that connection between the two events, most health experts say, is as fallacious in the world of medicine as it is in the field of logic.3

An outbreak of measles several weeks ago at Disneyland in Southern California focused minds and deepened concerns. It was as if the amusement park had become the tragic kingdom. Dozens of measles cases have spread across California. Arizona and other nearby states reported their own eruptions of this nasty illness, which officialdom had pronounced essentially eradicated in this country as recently as 2000.4

But it is back. In 2014, there were 644 cases in 27 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Should the pace set in January continue, the numbers could go still higher in 2015. While no one is known to have died in the new outbreaks, the lethal possibilities cannot be shrugged off. If the past is a guide, one or two of every 1,000 infected people will not survive.5

“If the past is a guide, one or two of every 1,000 infected people will not survive.”

To explore how matters reached this pass, Retro Report, a series of video documentaries studying major news stories of the past and their consequences, offers this special episode. It turns on a seminal moment in anti-vaccination resistance. This was an announcement in 1998 by a British doctor who said he had found a relationship between the M.M.R. vaccine—measles, mumps, rubella—and the onset of autism.6

Typically, the M.M.R. shot is given to infants at about 12 months and again at age 5 or 6. This doctor, Andrew Wakefield, wrote that his study of 12 children showed that the three vaccines taken together could alter immune systems, causing intestinal woes that then reach, and damage, the brain. In fairly short order, his findings were widely rejected as—not to put too fine a point on it—bunk. Dozens of epidemiological studies found no merit to his work, which was based on a tiny sample. The British Medical Journal went so far as to call his research “fraudulent.” The British journal Lancet, which originally published Dr. Wakefield’s paper, retracted it. The British medical authorities stripped him of his license.7

Nonetheless, despite his being held in disgrace, the vaccine-autism link has continued to be accepted on faith by some. Among the more prominently outspoken is Jenny McCarthy, a former television host and Playboy Playmate, who has linked her son’s autism to his vaccination: He got the shot, and then he was not O.K. Post hoc, etc.8

Steadily, as time passed, clusters of resistance to inoculation bubbled up. While the nationwide rate of vaccination against childhood diseases has stayed at 90 percent or higher, the percentage in some parts of the country has fallen well below that mark. Often enough, these are places whose residents tend to be well off and well educated, with parents seeking exemptions from vaccinations for religious or other personal reasons.9

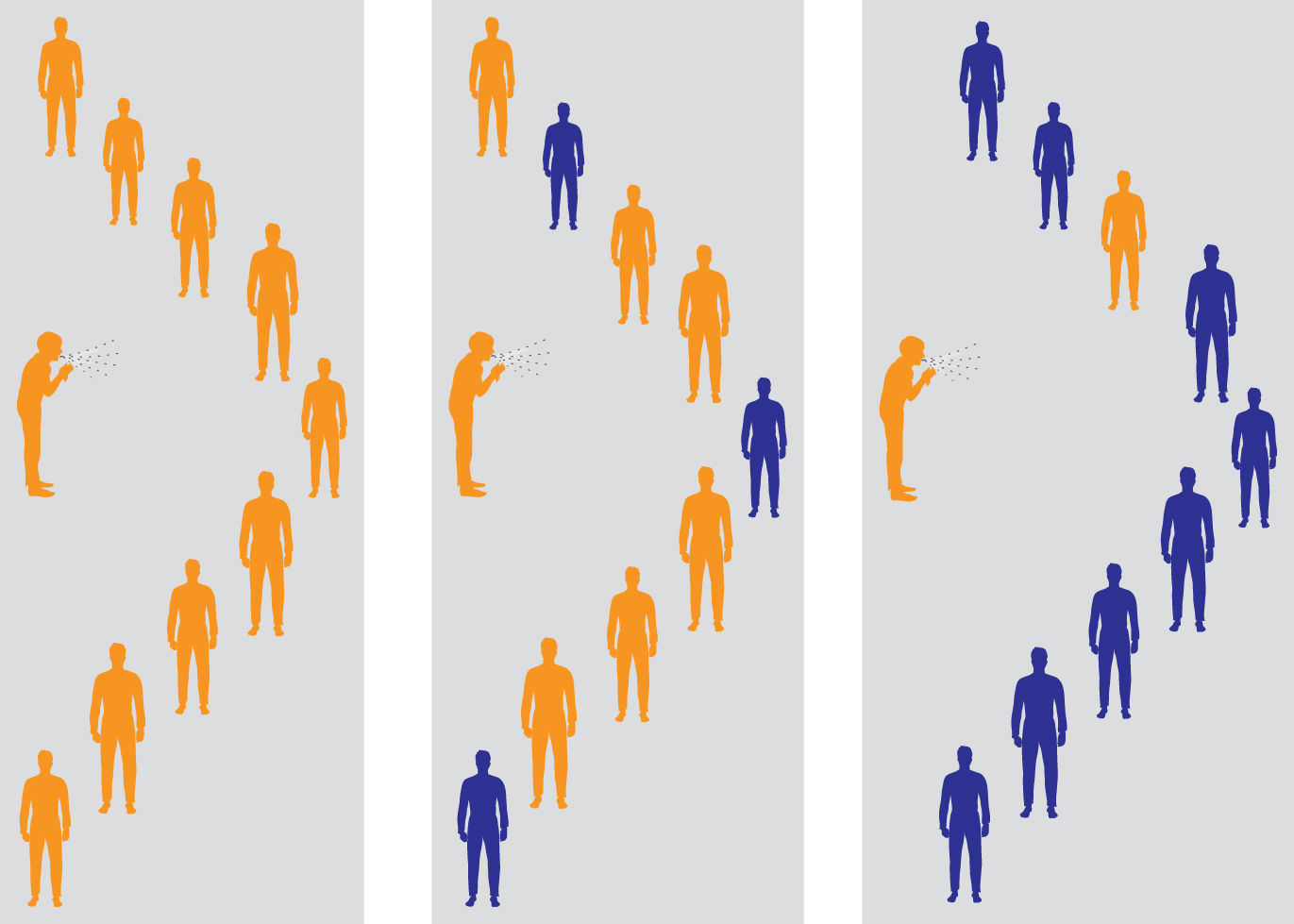

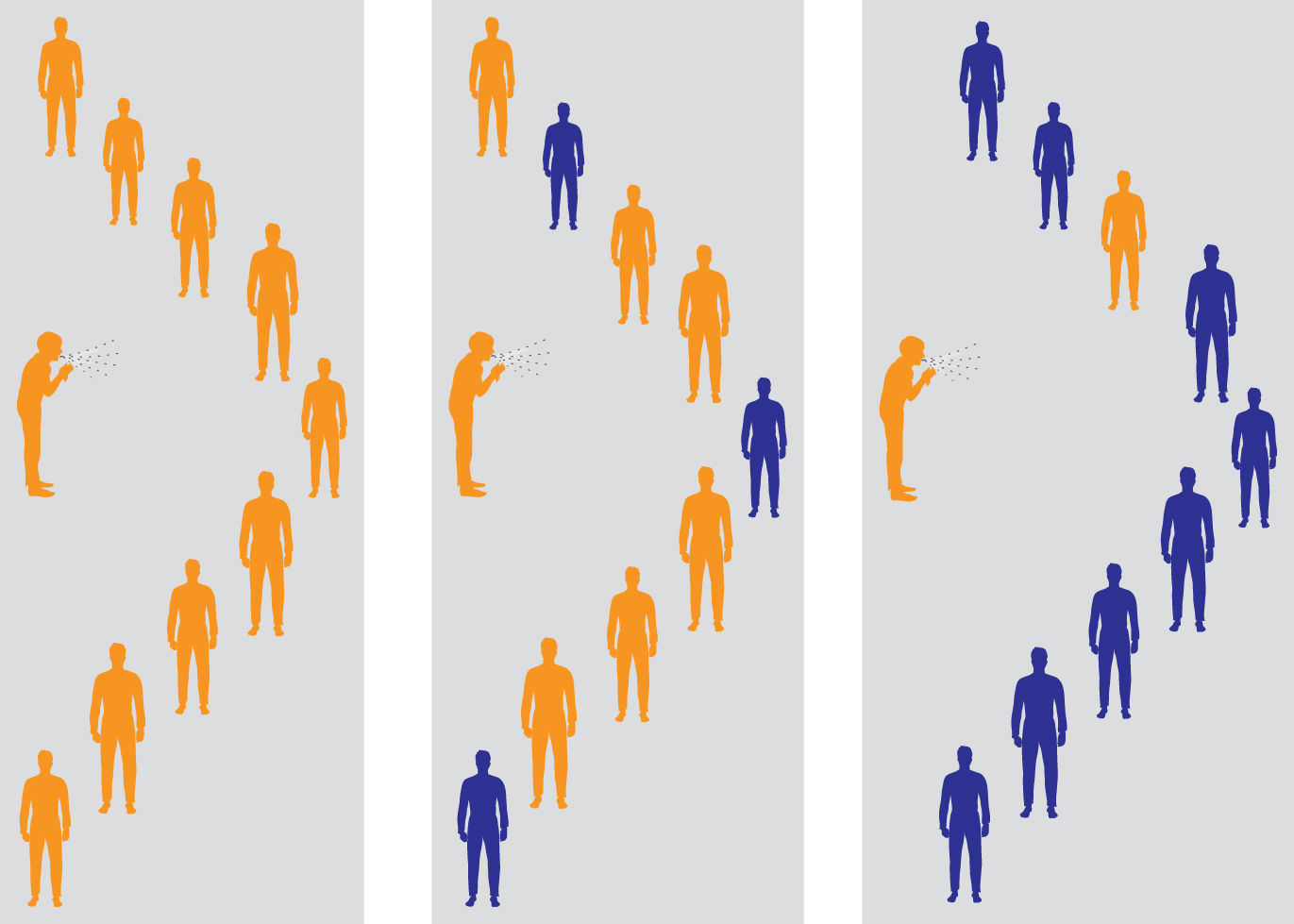

At the heart of the matter is a concept known as herd immunity. It means that the overall national rate of vaccination is not the only significant gauge. The rate in each community must also be kept high to ensure that pretty much everyone will be protected against sudden disease, including those who have not been immunized. A solid display of herd immunity reduces the likelihood in a given city or town that an infected person will even brush up against, let alone endanger, someone who could be vulnerable, like a 9-year-old whose parents rejected inoculations, or a baby too young for the M.M.R. shot. Health professionals say that a vaccination rate of about 95 percent is needed to effectively protect a community. Fall much below that level and trouble can begin.10

Mass vaccinations have been described by the C.D.C. as among the “10 great public health achievements” of the 20th century, one that had prevented tens of thousands of deaths in the United States. Yet diseases once presumed to have been kept reasonably in check are bouncing back. Whooping cough is one example. Measles draws especially close attention because it is highly infectious. Someone who has it can sneeze in a room, and the virus will linger in the air for two hours. Any unvaccinated person who enters that room risks becoming infected and, of course, can then spread it further. Disneyland proved a case in point. The measles outbreak there showed that it is indeed a small world, after all.11

What motivates vaccine-averse parents? One factor may be the very success of the vaccines. Several generations of Americans lack their parents’ and grandparents’ visceral fear of polio, for example. For those people, “you might as well be protecting against aliens—these are things they’ve never seen,” said Seth Mnookin, who teaches science writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and is the author of The Panic Virus, a 2011 book on vaccinations and their opponents.12

Mr. Mnookin, interviewed by Retro Report, said skepticism about inoculations is “one of those issues that seem to grab people across the political spectrum.” It goes arm in arm with a pervasive mistrust of many national institutions: the government that says vaccinations are essential, news organizations that echo the point, pharmaceutical companies that make money on vaccines, scientists who have hardly been shown to be error-free.13

Then, too, Mr. Mnookin said, scientists don’t always do themselves favors in their choice of language. They tend to shun absolutes, and lean more toward constructions on the order of: There is no vaccine-autism link “to the best of our knowledge” or “as far as we know.” Those sorts of qualifiers leave room for doubters to question how much the lab guys do, in fact, know.14

Thus far, the Disneyland measles outbreak has failed to deter the more fervent anti-vaccine skeptics. “Hype.” That is how the flurry of concern in California and elsewhere was described by Barbara Loe Fisher, president of the National Vaccine Information Center, an organization that takes a dim view of vaccinations. The hype, Ms. Fisher said in a Jan. 28 post on her group’s website, “has more to do with covering up vaccine failures and propping up the dissolving myth of vaccine acquired herd immunity than it does about protecting the public health.” Clearly, she remained untroubled that most health professionals regard her views as belonging somewhere in Fantasyland.15

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A CAUSE-AND-EFFECT ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A CAUSE-AND-EFFECT ARGUMENT

- What is the discredited vaccine study mentioned in the title? In general terms, what “impact on public health” has this study had?

- Why does Haberman begin his essay by discussing the post hoc fallacy? Define this fallacy. How does it apply to the vaccination debate?

- In paragraph 9, Haberman cites the steady rise of “resistance to inoculation.” What has caused this rise? What has been the result of this resistance?

- What is herd immunity? Why is it of central importance in the vaccination debate?

- In paragraph 12, Haberman asks, “What motivates vaccine-averse parents?” How does he answer this question? Do you agree with him? Explain.

- Why does Haberman quote Barbara Loe Fisher in his conclusion? Is he creating a straw man here? Why or why not?

Stemwedel’s argument appeared in Scientific American in June 2013.

JANET D. STEMWEDEL

SAYING NO TO VACCINES

At my last visit to urgent care with one of my kids, the doctor who saw us mentioned that there is currently an epidemic of pertussis (whooping cough) in California, one that presents serious danger for the very young children (among others) hanging out in the waiting area. We double-checked that both my kids are current on their pertussis vaccinations (they are). I checked that I was current on my own pertussis vaccination back in December when I got my flu shot.1

Sharing a world with vulnerable little kids, it’s just the responsible thing to do.2

You’re already on the Internet reading about science and health, so it will probably come as no surprise to you that California’s pertussis epidemic is a result of the downturn in vaccination in recent years, nor that this downturn has been driven in large part by parents worried that childhood vaccinations might lead to their kids getting autism, or asthma, or some other chronic disease. Never mind that study after study has failed to uncover evidence of such a link; these parents are weighing the risks and benefits (at least as they understand them) of vaccinating or opting out and trying to make the best decision they can for their children.3

The problem is that the other children with which their children are sharing a world get ignored in the calculation.4

Of course, parents are accountable to the kids they are raising. They have a duty to do what is best for them, as well as they can determine what that is. They probably also have a duty to put some effort into making a sensible determination of what’s best for their kids (which may involve seeking out expert advice, and evaluating who has the expertise to be offering trustworthy advice).5

But parents and kids are also part of a community, and arguably they are accountable to other members of that community. I’d argue that members of a community may have an obligation to share relevant information with each other—and, to avoid spreading misinformation, not to represent themselves as experts when they are not. Moreover, when parents make choices with the potential to impact not only themselves and their kids but also other members of the community, they have a duty to do what is necessary to minimize bad impacts on others. Among other things, this might mean keeping your unvaccinated-by-choice kids isolated from kids who haven’t been vaccinated because of their age, because of compromised immune function, or because they are allergic to a vaccine ingredient. If you’re not willing to do your part for herd immunity, you need to take responsibility for staying out of the herd.6

Otherwise, you are a free-rider on the sacrifices of the other members of the community, and you are breaking trust with them.7

I know from experience that this claim upsets non-vaccinating parents a lot. They imagine that I am declaring them bad people, guilty of making a conscious choice to hurt others. I am not. However, I do think they are making a choice that has the potential to cause great harm to others. If I didn’t think that pointing out the potential consequences might be valuable to these non-vaccinating parents, at least in helping them understand more fully what they’re choosing, I wouldn’t bother.8

So here, let’s take a careful look at my claim that vaccination refuseniks are free-riders.9

First, what’s a free-rider?10

In the simplest terms, a free-rider is someone who accepts a benefit without paying for it. The free-rider is able to partake of this benefit because others have assumed the costs necessary to bring it about. But if no one was willing to assume those costs (or indeed, in some cases, if there is not a critical mass of people assuming those costs), then that benefit would not be available, either.11

Thus, when I claim that people who opt out of vaccination are free-riders on society, what I’m saying is that they are receiving benefits for which they haven’t paid their fair share—and that they receive these benefits only because other members of society have assumed the costs by being vaccinated.12

Before we go any further, let’s acknowledge that people who choose to vaccinate and those who do not probably have very different understandings of the risks and benefits, and especially of their magnitudes and likelihoods. Ideally, we’d be starting this discussion about the ethics of opting out of vaccination with some agreement about what the likely outcomes are, what the unlikely outcomes are, what the unfortunate-but-tolerable outcomes are, and what the to-be-avoided-at-all-costs outcomes are.13

That’s not likely to happen. People don’t even accept the same facts (regardless of scientific consensus), let alone the same weightings of them in decision making.14

But ethical decision making is supposed to help us get along even in a world where people have different values and interests than our own. So, plausibly, we can talk about whether certain kinds of choices fit the pattern of free-riding even if we can’t come to agreement on probabilities and a hierarchy of really bad outcomes.15

So, let’s say all the folks in my community are vaccinated against measles except me. Within this community (assuming I’m not wandering off to exotic and unvaccinated lands, and that people from exotic and unvaccinated lands don’t come wandering through), my chances of getting measles are extremely low. Indeed, they are as low as they are because everyone else in the community has been vaccinated against measles—none of my neighbors can serve as a host where the virus can hang out and then get transmitted to me. (By the way, the NIH has a nifty Disease Transmission Simulator that you can play around with to get a feel for how infectious diseases and populations whose members have differing levels of immunity interact.)16

I get a benefit (freedom from measles) that I didn’t pay for. The other folks in my community who got the vaccine paid for it.17

In fact, it usually doesn’t require that everyone else in the community be vaccinated against measles for me to be reasonably safe from it. Owing to “herd immunity,” measles is unlikely to run through the community if the people without immunity are relatively few and well interspersed with the vaccinated people. This is a good thing, since babies in the U.S. don’t get their first vaccination against measles until 12 months, and some people are unable to get vaccinated even if they’re willing to bear the cost (e.g., because they have compromised immune systems or are allergic to an ingredient of the vaccine). And, in other cases, people may get vaccinated but the vaccines might not be fully effective—if exposed, they might still get the disease. Herd immunity tends to protect these folks from the disease—at least as long as enough of the herd is vaccinated.18

If too few members of the herd are vaccinated, even some of those who have borne the costs of being vaccinated (because even very good vaccines can’t deliver 100 percent protection to 100 percent of the people who get them), or who would bear those costs were they able (owing to their age or health or access to medical care), may miss out on the benefit. Too many free-riders can spoil things even for those who are paying their fair share.19

A standard reply from non-vaccinating parents is that their unvaccinated kids are not free-riders on the vaccinated mass of society because they actually get diseases like chicken pox, pertussis, and measles (and are not counting on avoiding the other diseases against which people are routinely vaccinated). In other words, they argue, they didn’t pay the cost, but they didn’t get the benefit, either.20

Does this argument work?21

I’m not convinced that it does. First off, even though unvaccinated kids may get a number of diseases that their vaccinated neighbors do not, it is still unlikely that they will catch everything against which we routinely vaccinate. By opting out of vaccination but living in the midst of a herd that is mostly vaccinated, non-vaccinating parents significantly reduce the chances of their kids getting many diseases compared to what the chances would be if they lived in a completely unvaccinated herd. That statistical reduction in disease is a benefit, and the people who got vaccinated are the ones paying for it.22

Now, one might reply that unvaccinated kids are actually incurring harm from their vaccinated neighbors, for example if they contract measles from a recently vaccinated kid shedding the live virus from the vaccine. However, the measles virus in the MMR vaccine is an attenuated virus—which is to say, it’s quite likely that unvaccinated kids contacting measles from vaccinated kids will have a milder bout of measles than they might have if they had been exposed to a full-strength measles virus out in the wild. A milder case of measles is a benefit, at least when the alternative is a severe case of measles. Again, it’s a benefit that is available because other people bore the cost of being vaccinated.23

Indeed, even if they were to catch every single disease against which we vaccinate, unvaccinated kids would still reap further benefits by living in a society with a high vaccination rate. The fact that most members of society are vaccinated means that there is much less chance that epidemic diseases will shut down schools, industries, or government offices, much more chance that hospitals and medical offices will not be completely overwhelmed when outbreaks happen, much more chance that economic productivity will not be crippled and that people will be able to work and pay the taxes that support all manner of public services we take for granted. The people who vaccinate are assuming the costs that bring us a largely epidemic-free way of life. Those who opt out of vaccinating are taking that benefit for free.24

“Those who opt out of vaccinating are taking that benefit for free.”

I understand that the decision not to vaccinate is often driven by concerns about what costs those who receive the vaccines might bear, and whether those costs might be worse than the benefits secured by vaccination. Set aside for the moment the issue of whether these concerns are well grounded in fact. Instead, let’s look at the parallel we might draw: If I vaccinate my kids, no matter what your views about the etiology of autism and asthma, you are not going to claim that my kids getting their shots raise your kids’ odds of getting autism or asthma. But if you don’t vaccinate your kids, even if I vaccinate mine, your decision does raise my kids’ chance of catching preventable infectious diseases. My decision to vaccinate doesn’t hurt you (and probably helps you in the ways discussed above). Your decision not to vaccinate could well hurt me.25

The asymmetry of these choices is pretty unavoidable.26

Here, it’s possible that a non-vaccinating parent might reply by saying that it ought to be possible for her to prioritize protecting her kids from whatever harms vaccination might bring to them without being accused of violating a social contract.27

The herd immunity thing works for us because of an implicit social contract of sorts: those who are medically able to be vaccinated get vaccinated. Obviously, this is a social contract that views the potential harms of the diseases as more significant than the potential harms of vaccination. I would argue that under such a social contract, we as a society have an obligation to take care of those who end up paying a higher cost to achieve the shared benefit.28

But if a significant number of people disagree, and think the potential harms of vaccination outweigh the potential harms of the diseases, shouldn’t they be able to opt out of this social contract?29

The only way to do this without being a free-rider is to opt out of the herd altogether—or to ensure that your actions do not bring additional costs to the folks who are abiding by the social contract. If you’re planning on getting those diseases naturally, this would mean taking responsibility for keeping the germs contained and away from the herd (which, after all, contains members who are vulnerable owing to age, medical reasons they could not be vaccinated, or the chance of less than complete immunity from the vaccines). No work, no school, no supermarkets, no playgrounds, no municipal swimming pools, no doctor’s office waiting rooms, nothing while you might be able to transmit the germs. The whole time you’re able to transmit the germs, you need to isolate yourself from the members of society whose default assumption is vaccination. Otherwise, you endanger members of the herd who bore the costs of achieving herd immunity while reaping benefits (of generally disease-free work, school, supermarkets, playgrounds, municipal swimming pools, doctor’s office waiting rooms, and so forth, for which you opted out of paying your fair share).30

Since you’ll generally be able to transmit these diseases before the first symptoms appear—even before you know for sure that you’re infected—you will not be able to take regular contact with the vaccinators for granted.31

And if you’re traveling to someplace where the diseases whose vaccines you’re opting out of are endemic, you have a duty not to bring the germs back with you to the herd of vaccinators. Does this mean quarantining yourself for some minimum number of days before your return? It probably does. Would this be a terrible inconvenience for you? Probably so, but the 10-month-old who catches the measles you bring back might also be terribly inconvenienced. Or worse.32

Here, I don’t think I’m alone in judging the harm of a vaccine refusenik giving an infant pertussis as worse than the harm in making a vaccine refusenik feel bad about violating a social contract.33

An alternative, one which would admittedly require some serious logistical work, might be to join a geographically isolated herd of other people opting out of vaccination, and to commit to staying isolated from the vaccinated herd. Indeed, if the unvaccinated herd showed a lower incidence of asthma and autism after a few generations, perhaps the choices of the members of the non-vaccinating herd would be vindicated.34

In the meantime, however, opting out of vaccines but sharing a society with those who get vaccinated is taking advantage of benefits that others have paid for and even threatening those benefits. Like it or not, that makes you a free-rider.35

![]() ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A CAUSEAND-EFFECT ARGUMENT

ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A CAUSEAND-EFFECT ARGUMENT

- Stemwedel’s argument in paragraph 13 includes the word ethics. Is she appealing strictly to ethos in this essay, or does she also appeal to logos and pathos? For example, what appeal is she using in the first two paragraphs by presenting herself as a responsible parent?

- Throughout this essay—for example, in paragraph 7 and in the conclusion—Stemwedel uses the term free-rider. According to Stermwedel, what does this term mean? What are the connotations of this term? How does she apply this term to the vaccination debate?

- In paragraph 6, Stemwedel says, “If you’re not willing to do your part for herd immunity, you need to take responsibility for staying out of the herd.” Does offering parents this option undercut her strong position in favor of universal vaccination? Could she be accused of committing the either/or fallacy? Explain.

- Why does Stemwedel call herd immunity “an implicit social contract of sorts” (para. 28)?

- According to Stemwedel, how do “non-vaccinating parents” (20) defend themselves against the charge of being free-riders? How does Stemwedel refute their arguments?

Vidula’s argument was posted online at MIT.edu in a collection of writing about medicine and technology.

MAHESH VIDULA

INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS VS. PUBLIC HEALTH: THE VACCINATION DEBATE

A pediatrician enters Examination Room B, ready for a routine check-up with a two-month-old infant. He greets the mother, and begins to discuss the next step in infant care: receiving the required vaccinations. As he starts to ask the mother to schedule an appointment with the receptionist, she interrupts, “Sorry, doctor. My child will not be immunized.”1

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) defines vaccination as the injection of weak disease-causing agents that help the body develop immunity against specific infectious diseases (CDC, How Vaccines Prevent Disease 2009). Scientists hope that “through vaccination, children develop immunity without suffering from the actual diseases that vaccines prevent” (CDC, How Vaccines Prevent Disease 2009). States often require that children receive vaccinations against particularly dangerous diseases, such as polio, varicella (chicken pox), diphtheria/tetanus/pertussis (DTP), Haemophilus influenza B (Hib), and measles/mumps/rubella (MMR) (Goodman 2007: 266). In the U.S., unvaccinated children may suffer severe consequences, such as being prevented from attending schools, camps, sports, and other organized group activities (Park 2008). While proponents of mandatory vaccinations believe that these procedures are absolutely necessary for maintaining public health, opponents argue that compulsory immunizations infringe on the rights of individuals to control their own bodies and the bodies of their minor children.2

The controversy surrounding compulsory vaccinations in the United States is not new. In 1809, Massachusetts passed a law that “granted city boards of health the authority to require vaccination ‘when necessary for public health or safety’” (Mariner 2005: 582). When the state required all residents to receive a smallpox vaccine in 1902, 46-year-old Henning Jacobson declined the vaccine, claiming that he had suffered “bad reactions to earlier vaccines” (Mariner 2005: 582). Due to his refusal of the vaccine, he was fined five dollars by the state. After an unsuccessful challenge to the fine in the Massachusetts State Supreme Judicial Court, he appealed in 1905 to the United States Supreme Court in the famous case, Jacobson v. Massachusetts (Mariner 2005: 582). Despite Jacobson’s argument that compulsory immunization violated his Fourteenth Amendment right to personal liberty, the Supreme Court ruled against him (Jacobson v. Massachusetts, Oyez Project). According to the 1905 Supreme Court ruling, the state had the right to mandate the smallpox vaccine since “[the] safety and the health of the people of Massachusetts are for that Commonwealth to guard and protect” (Jacobson v. Massachusetts, LSU Law Center).3

Similar to the Supreme Court decision in Jacobson v. Massachusetts, contemporary advocates for mandatory vaccinations contend that immunizations are necessary to maintain public health. For one, vaccinations have effectively curbed the spread of several deadly infectious diseases in the United States and around the world. For instance, before the development of the poliomyelitis vaccine by Jonas Salk in the 1950s, “13,000 to 20,000 cases of paralytic polio were reported each year” (CDC 2007). Poliomyelitis is a highly contagious and dangerous viral infection; children under five are most commonly affected. Since the polio virus affects the nervous system, some children who contract the disease become paralyzed and may even lose breathing ability (WHO: Poliomyelitis). In the early to mid 20th century, some children with polio had to use an iron lung, a machine to pump air into their lungs, to breathe. In the 1930s, these devices often cost as much as a home (National Museum of American History, The Iron Lung). However, by 1964, the widespread use of the polio vaccine essentially eradicated the disease in America (Health and Human Services). As described by science journalist Alan Dove, “The benefit to the United States alone for [the polio vaccine] runs into the trillions of dollars. The social impact has been incalculable. The crutches, wheelchairs, and iron lungs of polio victims have at last been banished from children’s and parents’ nightmares” (PICO).4

Other dangerous infectious diseases virtually eliminated in America by vaccinations include diphtheria and pertussis. Both diphtheria and pertussis can cause severe breathing complications in children (CDC Diphtheria). Over 206,000 people were reported to have diphtheria in 1921, and there were 150,000–260,000 cases of pertussis per year (CDC 2007). Following the distribution of vaccines for these diseases, the number of reported disease events fell dramatically, and scientists believe that the immunizations directly lowered the incidence of disease (CDC 2007). For instance, recent studies report that there are currently 97.56 percent fewer pertussis cases in the United States, than would be expected without mass immunization, due to compulsory vaccination programs (Health and Human Services). Moreover, as the CDC argues, “[those] same germs exist today, but babies are now protected by vaccines, [and so] we do not see these diseases as often” (CDC, How Vaccines Prevent Disease 2009). For these reasons, supporters of mandatory vaccinations argue that immunizations in the United States have been very effective. After noting the large impact of vaccinations on American public health, philanthropists such as Bill and Melinda Gates have begun funding vaccine research and distribution to improve the quality of health in third world countries (Gates Foundation).5

“Following the distribution of vaccines for these diseases, the number of reported disease events fell dramatically.”

In addition, advocates of compulsory vaccinations believe that through immunization, a person not only avoids contracting the disease himself, but also prevents spreading the illness to others (Why Immunize 2009). According to a study by Salmon et al. from 1985 to 1992 in the United States, the incidence of measles increased by 35 times in children without the vaccination (Omer et al. 2009: 1983). Additional studies showed that unvaccinated children had a higher risk for developing mumps and pertussis as well (Omer et al. 2009: 1983). While aiming to identify the reasons for lower rates of disease in some communities, researchers found that “[school] immunization laws have had a remarkable impact on vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States” (Orenstein and Hinman 1999: S19).6

Although proponents believe that vaccines are important in ensuring personal safety, they also support the necessity of immunizations for preserving the health of the community. In an interview with USA Today, Dr. Lance Rodewald, Director of the CDC Immunization Services Division, suggested that receiving vaccinations is a social responsibility, since an unvaccinated sick person can infect many more people (Leblanc 2007). As Dr. Rodewald stated, “When you choose not to get a vaccine, you’re not just making a choice for yourself, you’re making a choice for the person sitting next to you” (Leblanc 2007). Moreover, several studies indicate that disease incidence rises in communities “when there is geographic aggregation of persons refusing vaccination” (Omer et al. 2009: 1983). For example, in a 1987 measles outbreak at a Colorado school, unvaccinated children infected 11 percent of vaccinated students (Feikin et al. 2000: 3148). Supporters also encourage healthy children to receive vaccinations, to protect other children unable to be vaccinated due to health conditions or young age (Omer et al. 2009: 1984). Some children may fail to respond to vaccines due to weak immune systems, and therefore rely on “other parents to keep germs out of circulation by vaccinating their kids” (Szabo 2010). As a result, supporters of compulsory immunizations believe that parents of healthy children have a moral responsibility to have their offspring vaccinated (Szabo 2010).7

According to mandatory immunization advocates, vaccines also prevent disease outbreaks for future generations. For example, the CDC argues that if vaccinations ceased, “[diseases] that are almost unknown would stage a comeback [and before] long we would see epidemics of diseases that are nearly under control today” (CDC, Why Immunize 2009). In August 2008, the New York Times reported 131 cases of measles from January 2008 to July 2008 in the United States; the majority of infected patients had not received the measles (MMR) vaccination (Harris 2008). Besides gathering data on infectious disease incidence, the CDC has also projected the number of cases of certain diseases expected if vaccinations were discontinued. For instance, the CDC predicted that if people did not receive the MMR vaccination, 2.7 million individuals around the world would die of measles every year (CDC 2007). Moreover, advocates argue that compulsory vaccinations may eradicate diseases for future generations. Drawing from the success of the smallpox vaccine, which eliminated the smallpox virus and made it unnecessary for future generations to receive the vaccine, the CDC contends that other diseases may similarly be eradicated if immunizations continue. The CDC states, “If we keep vaccinating now, parents in the future may be able to trust that diseases like polio and meningitis won’t infect, cripple, or kill children” (Why Immunize 2009). Due to the significant global health benefits of immunization, public health officials such as immunologist Anthony Fauci argue that any small risks associated with vaccinations are “acceptable” (Frontline: The Vaccine War). In the 2010 public television documentary, Frontline: The Vaccine War, Fauci addresses the risks of vaccination:8

What is the risk of injecting something into someone’s arm? The risk is that a certain proportion of people will get swelling and a little bit of pain, lasting from an hour to a day. That is a very acceptable risk. A very, very, very small percentage of people will get an allergic reaction…. And then there’s a subset of a very, very, very, very small percentage of those who actually can get a serious reaction. But if you look at that, the risk of that is so minisculely small as to be completely outweighed by the benefit.

Overall, immunization supporters believe that compulsory vaccinations are justified, since they protect the public health in the present and future, and tend to have acceptable risks.9

Although proponents tout the efficacy and need of vaccinations in the United States and other countries, opponents argue against compulsory immunization for a variety of reasons including harmful side effects, individual liberty, and religious freedom. Compared to all the other reasons for avoiding immunization, “the most frequent reason for nonvaccination, stated by 69 percent of the parents, was a concern that the vaccine might cause harm” (Omer et al. 2009: 1985). It is widely known that vaccines have possible side effects, which are published by the CDC. For instance, a reaction to the varicella vaccine can range from a rash to severe infection (CDC 2010). Freed et al. found in 2010 that despite reassurances from the CDC and FDA that vaccines “undergo a rigorous review of laboratory and clinical data to ensure the safety, efficacy, purity, and potency” (FDA 2009), some parents continue to believe that vaccinations have strong potential to hurt their children (Freed et al. 2010: 654). Although no strong scientific evidence exists to support these claims, some people also fear that vaccinations may predispose children to Type 1 diabetes (Levitsky 2004: 1382).10

The most prevalent concern among some contemporary American parents is whether vaccinations will result in autism (Freed et al. 2010: 657). The fear that vaccinations cause autism in some children gained prominence in 1998 when British researcher Dr. Andrew Wakefield published an article in The Lancet that suggested a link between autism and the MMR vaccine (Harrell 2010). Moreover, research groups found that several vaccines contained thimerosal, a mercury compound used to preserve vaccines (Park 2008). Since at high exposures, mercury may “cause neurologic damage, the presence of organic mercury in several common vaccines aroused particular concern” (Levitsky 2004: 1381). For instance, the National Autism Association urged the CDC to remove thimerosal from vaccines, and suggested that it contributed to the rise in autism cases since “at the same time that the incidence of autism was growing, the number of childhood vaccines containing thimerosal was growing” (National Autism Association). Although The Lancet later retracted Wakefield’s article due to his unethical scientific method, and several later studies showed no link between autism and the MMR vaccine or thimerosal (Harrell 2010), a study by Freed et al. in 2010 reported that “[more than] 1 in 5 [parents], continue to believe that some vaccines cause autism in otherwise healthy children” (2010: 657). In his Time article, journalist Karl Taro Greenfield suggests that parents may continue to believe that autism is caused by vaccinations due to their distrust in scientific research and reliance on their emotions (2010). When a prominent anti-vaccination activist was asked about the lack of scientific proof linking vaccinations to autism, she replied, “My science is [my son]. He’s at home. That’s my science” (Greenfield 2010).11

However, some parents opposing vaccinations do have faith in science, but believe that the research is misguided or incomplete. In Frontline: The Vaccine War, parents express their frustration towards research groups that claim that autism is not linked to the MMR vaccine or thimerosal. They believe that some psychological transformation occurred in their children after receiving the vaccine, and yearn for a scientific understanding of why their children suffered. As one parent expressed, “My kid got six vaccines in one day, and he regressed. You don’t have any science that can show me the regression wasn’t triggered by the six vaccines…. We need to ask the question as to why the regression took place” (Frontline: The Vaccine War). In their view, epidemiological studies do not prove the safety of vaccines. Instead, these parents encourage scientists to investigate the physiological effects of receiving the vaccine load. In the documentary, one parent declared, “You have to do bench science. You have to look at the human body and what occurs in terms of changes in immune function, brain function. You can’t just do epidemiology where you’re comparing groups of children against each other” (Frontline: The Vaccine War). Therefore, before completely dismissing the possibility that vaccines can lead to negative side effects, some parents ask for more thorough scientific studies that analyze other vaccines, ingredients, and other risk factors that may predispose a child to a vaccine reaction (Frontline: The Vaccine War).12

Parents may also distrust the integrity of a state mandate, which can lead to their opposition to a particular vaccination. Gardasil, a vaccine created by Merck, prevents cervical cancer by targeting the human papillomavirus (HPV) (Savage 2007: 666). In 2007, Republican Governor of Texas Rick Perry mandated that all girls entering sixth grade must be vaccinated with Gardasil (Peterson 2/2/2007). In his plan, uninsured girls between ages nine and eighteen would receive free vaccinations, and Medicaid would cover women between 19 and 21 (Peterson 2/2/2007). However, due to the incensed debate that followed this decision, and the state’s overall rejection of this idea, Perry’s order was vetoed and revoked on April 25, 2007 (Blumenthal 4/26/07).13

A major source of opposition to the mandatory HPV vaccination resulted from the link between the Texas government and Merck, which drew suspicion around the motivation for the executive order. According to internal documents, Merck donated $5,000 to Rick Perry and another $5,000 to eight lawmakers on the same day the chief of staff held a meeting to discuss whether to mandate the HPV vaccine (Peterson 2/21/07). Merck had also previously made a $6,000 donation to the governor’s reelection campaign (Peterson 2/2/07). Therefore, the financial connection between the Texas government and Merck gave some Texans the idea that the vaccination mandate was not in the interest of safeguarding women’s health, but rather for improving Merck’s financial situation.14

Furthermore, some people may follow certain religions that oppose vaccination mandates. People seeking religious exemption from vaccinations argue that “the free-exercise clause of the First Amendment mandates state accommodation for members of religious groups who object to the vaccinations on religious grounds” (First Amendment Center). For instance, Christian Scientists prefer spiritual healing to Western medicine, and therefore do not completely support vaccinations (DeLacy Lecture). The founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, wrote in 1896, “A calm, Christian state of mind is a better preventive of contagion than a drug, or than any other possible sanative method; and the ‘perfect Love’ that ‘casteth out fear’ is a sure defense” (Eddy, “Contagion”). Therefore, rather than relying on medications or vaccinations, Christian Scientists prefer “watching [their thoughts], guarding against influences that would pull [them] down, and daily taking time for silent, sacred moments alone with God” (DeLacy Lecture) while fighting diseases. Since vaccinations are against their religious beliefs, Christian Scientists often file for religious exemptions from compulsory immunizations.15

“Since vaccinations are against their religious beliefs, Christian Scientists often file for religious exemptions from compulsory immunizations.”

However, this refusal of vaccinations has had negative repercussions for some Christian Scientists. In 1989, 15 Christian Scientists in Boston were infected with measles, after a “worshiper carrying the virus attended Sunday school services at the Christian Science campus” (Smith 2006). In 2006, a Boston Christian Scientist also contracted measles (Smith 2006). In both cases, to control the spread of measles, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health asked the infected Christian Scientists to remain isolated from the public, and to refrain from interacting with uninfected people (Smith 2006). In an interview with the Boston Globe, Boston’s Chief Medical Officer Dr. Alfred DeMaria commented that Christian Scientists tend to comply with quarantines, since “[they] see it as the other side of the coin for not being vaccinated” (Smith 2006).16

Additionally, some opponents of compulsory vaccinations cite “herd immunity” as a reason to avoid immunizations. The concept of “herd immunity” is that if many people are vaccinated in a community, those not vaccinated will still enjoy protection since “the disease has little opportunity for an outbreak” (CDC Glossary). With regard to childhood vaccinations, some parents believe that “if everyone else is protected, then so is [their] child so why take even the minute risk of any vaccine side effect” (Calandrillo 2004: 361). Therefore, it is clear that some opponents of mandatory vaccinations believe that they can “take advantage of the benefit created by the participation of others in the vaccination program while refusing to participate and share equitably in the risks and obligations of the program” (Diekema 2009: 92). However, proponents often argue that herd immunity is falling due to the increasing numbers of people failing to receive vaccinations (Calandrillo 2004: 361).17

Finally, opponents of compulsory immunizations do not believe it is their social responsibility to protect the public health, and they instead value their individual and family rights. After understanding the possible severe effects of vaccinations on their children, some parents refuse to take the risks associated with immunization. In their view, protecting the lives of their children holds greater importance than maintaining the health of the community. For example, a suburban Chicago mother, who declined vaccinations for her two daughters, asserts:18

I don’t care about maintaining herd immunity, or protecting the health of the other sick children in the neighborhood. It’s not about them, it’s about my children. Who will protect my children if they develop some disability after receiving the vaccinations? … The only person who can protect them is me, and I am doing that by making sure they don’t get any problems from vaccinations…. I can make this choice for my children (Personal interview 3/25/10).

Similarly, other anti-vaccination parents believe that it is unreasonable to expect parents to risk their children’s lives for the sake of public health (Frontline: The Vaccine War). In The Vaccine War, one parent states, “Physicians have to get over the idea that they can tell people what to do and people are going to do it without questioning.” The fuel for this belief may be that parents desire to be the decision makers for their children, instead of having the government impose rules. If they succumb to the government’s every request, even those that could potentially harm their children’s health, some parents believe that they may slowly lose control over their children. As the suburban Chicago mother emphasizes, “What right does the government have over my children? I gave birth to them; no one else did. I have the right to choose what’s best for them…. Soon, the government may ask me to talk to my kids in a certain way or feed them only some foods. These are my children, and I make the choices” (Personal interview 3/25/10).19

The controversy surrounding compulsory vaccinations involves a wide variety of individuals, with different personal beliefs. Proponents of mandatory vaccinations focus on disease statistics, which demonstrate the need of immunizations in maintaining public health. However, opponents argue against these measures since they value their own personal liberty and children’s safety over public health, and they strive to protect their offspring by avoiding required vaccinations. From these two different perspectives, one primarily appealing to facts and the other largely to emotions, it is important to recognize the larger issue at hand. The debate regarding mandatory immunizations reflects the underlying conflict of individual rights versus the public good. Proponents of compulsory vaccinations may believe that improving and maintaining public health holds greater importance than preserving a person’s individual right to control his body. On the other hand, opponents may fear a growing lack of control over their bodies and the bodies of their minor children. They may reasonably imagine a future society, where people no longer have the right to decide how they wish to treat their bodies. As the compulsory immunization controversy continues, pediatricians should no longer assume parental consensus that children will automatically receive vaccinations.20

Works Cited

Blumenthal, Ralph. “Texas Legislators Block Shots for Girls against Cancer Virus.” The New York Times 26 Apr. 2007. Web. 02 May 2010.˂http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/26/us/26texas.html?ref=health˃.

Calandrillo, S. P. “Vanishing Vaccinations: Why Are So Many Americans Opting Out of Vaccinating Their Children?” University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform 2004; 37: 353–440.

“CDC National Vaccine Program Office: Glossary.” United States Department of Health and Human Services. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/glossary1.htm˃.

“CDC National Vaccine Program Office: The Effectiveness of Immunizations.” United States Department of Health and Human Services. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/concepts/intro6.htm˃.

“CDC — Vaccine History — Vaccine Safety.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 Jan. 2010. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/Vaccine_Monitoring/history.html˃.

DeLacy, Marceil. “Contagion Unmasked.” Lecture. Christian Science. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂christianscience.com/˃.

Diekema, D. S. “Choices Should Have Consequences: Failure to Vaccinate, Harm to Others, and Civil Liability.” Michigan Law Review First Impressions 2009; 107: 0–94.

“Diphtheria.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 6 Oct. 2005. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/diseaseinfo/diptheria_t.htm˃.

Dove, Alan. “PICO-History.” Columbia University. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://microbiology.columbia.edu/pico/Chapters/History.html˃.

Eddy, Mary Baker. “Contagion” (1896). Web. 10 July 2010. ˂http://www.endtime.org/library/mbe/contagion.html˃.

Feikin, D. R., Lezotte, D. C., Hamman, R. F., Salmon, D. A., Chen, R. T., Hoffman, R. E. “Individual and Community Risks of Measles and Pertussis Associated with Personal Exemptions to Immunization.” JAMA 2000; 284: 3145–3150.

Freed, G. L., Clark, S. J., Butchart, A. T., Singer, D. C., Davis, M. M. “Parental Vaccine Safety Concerns in 2009.” Pediatrics 2010; 125: 654–659.

Frontline: The Vaccine War. PBS, 27 Apr. 2010. Directed by Jon Palfreman. Web. 10 July 2010. ˂ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/vaccines/view/˃.

Goodman, Richard A. “Vaccination Mandates: The Public Health Imperative and Individual Rights.” Law in Public Health Practice. New York: Oxford UP, 2007. Print.

Greenfield, Karl T. “The Autism Vaccine Debate: Who’s Afraid of Jenny McCarthy?” Time. 25 Feb. 2010. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1967796-1,00.html˃.

Harrell, Eben. “Doctor in MMR-Autism Scare Ruled Unethical.” Time. 29 Jan. 2010. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1957656,00.html˃.

Harris, Gardiner. “Measles Cases Grow in Number, and Officials Blame Parents’ Fear of Autism.” The New York Times. 21 Aug. 2008. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/22/health/research/22measles.html?_r=2&fta=y˃.

“Jacobson v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1905).” LSU Law Center. 1998. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://biotech.law.lsu.edu/cases/vaccines/Jacobson_v_Massachusetts.htm˃.

“Jacobson v. Massachusetts, U.S. Supreme Court Case Summary & Oral Argument.” The Oyez Project /Build 6. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.oyez.org/cases/1901-1939/1904/1904_70˃.

Leblanc, Steve. “Parents Use Religion to Avoid Vaccines.” USAToday.com. 18 Oct. 2007. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-10-17-19819928_x.htm˃.

Levitsky, L. L. “Childhood Vaccinations and Chronic Illness.” New England Journal of Medicine 2004; 350: 1380–1382.

Mariner, W. K., Annas, G. J., Glantz, L. H. “Jacobson v Massachusetts: It’s Not Your Great-Great-Grandfather’s Public Health Law.” Am J Public Health 2005; 95: 581–590.

“NMAH: The Iron Lung and Other Equipment.” National Museum of American History. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://americanhistory.si.edu/polio/howpolio/ironlung.htm˃.

Omer, S. B., Salmon, D. A., Orenstein, W. A., deHart, M. P., Halsey, N. “Vaccine Refusal, Mandatory Immunization, and the Risks of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases.” New England Journal of Medicine 2009; 360: 1981–1988.

Orenstein, W. A., Hinman, A. R. “The Immunization System in the United States — the Role of School Immunization Laws.” Vaccine 1999; 17: S19-S24.

Park, Alice. “How Safe Are Vaccines?” Time. 21 May 2008. Web. 02 May 2010. http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1808438-2,00.html˃.

Peterson, Liz A. “Texas Gov. Orders Anti-Cancer Vaccine.” The Washington Post 2 Feb. 2007. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/02/02/AR2007020201528.html˃.

Peterson, Liz A. “Vaccine Meeting, Merck Donation Coincide.” The WashingtonPost 21 Feb. 2007. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/02/21/AR2007022102025.html˃.

“Religious Liberty in Public Life — Free-Exercise Clause Topic.” First Amendment Center Online. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.firstamendmentcenter.org/rel_liberty/free_exercise/..%5C..%5C/rel_liberty/free_exercise/topic.aspx?topic=vaccination˃.

Savage, Liz. “Proposed HPV Vaccine Mandates Rile Health Experts across the Country.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2007; 99: 665–666.

Smith, Stephen. “Measles Spread to Christian Scientist.” The Boston Globe 3 June 2006. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2006/06/03/measles_spreads_to_christian_scientist/˃.

Szabo, Liz. “Missed Vaccines Weaken ‘Herd Immunity’ in Children.” USAToday.com. 6 Jan. 2010. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2010-01-06-childhoodvaccines06_CV_N.htm˃.

“Vaccines.” Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.gatesfoundation.org/vaccines/pages/default.aspx˃.

“Vaccines.” U. S. Food and Drug Administration. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/default.htm˃.

“Vaccines: Vac-Gen/How Vaccines Prevent Disease.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 7 Aug. 2009. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vac-gen/howvpd.htm˃.

“Vaccines: Vac-Gen/What Would Happen If We Stopped Vaccinations.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 12 June 2007. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vac-gen/whatifstop.htm#intro˃.

“Vaccines: Vac-Gen/Why Immunize?” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 6 Aug. 2009. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vac-gen/why.htm˃.

“What Causes Autism.” National Autism Association. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.nationalautismassociation.org/thimerosal.php˃.

“WHO: Poliomyelitis.” World Health Organization. Jan. 2008. Web. 02 May 2010. ˂http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs114/en/index.html˃.

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A CAUSE-AND-EFFECT ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A CAUSE-AND-EFFECT ARGUMENT

- Does Vidula take a position on the issue of mandatory vaccination, or is his purpose in this essay simply to provide a context for the debate—for example, by presenting historical background and discussing religious objections to vaccination? Explain.

- What kind of audience is Vidula addressing? For example, is he writing for parents? For medical professionals? How can you tell?

- Vidula cites many experts and includes a lengthy works-cited list. What appeal is he making by using these strategies in his essay?

- What positive results of mandatory vaccination laws does Vidula identify?

- List the arguments against compulsory immunization. How does Vidula address these arguments? Does he dismiss them all, or does he believe some have merit? Do you see the writer as tolerant of those who oppose mandatory vaccination?

This piece was posted on February 11, 2015, to the online version of National Review.

BEN CARSON

VACCINATIONS ARE FOR THE GOOD OF THE NATION

There has been much debate recently over vaccination mandates, particularly in response to the measles outbreak currently taking place throughout the country.1

At this juncture, there have been 102 confirmed measles cases in the U.S. during 2015, with 59 of them linked to a December 2014 visit to the Disneyland theme park in Southern California. (It is important to note that 11 of the cases associated with Disneyland were detected last year and, consequently, fall within the 2014 measles count.) This large outbreak has spread to at least a half-dozen other states, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is currently requesting that all health care professionals “consider measles when evaluating patients with febrile rash and ask about a patient’s vaccine status, recent travel history and contact with individuals who have febrile rash illness.”2

One must understand that there is no specific antiviral therapy for measles and that 90 percent of those who are not vaccinated will contract measles if they are indeed exposed to the virus. This explains why Arizona health officials are monitoring more than 1,000 people after potential exposure to measles. These are pretty staggering numbers that should concern not only parents and children, but also the general populace.3

I have been asked many times throughout the past week for my thoughts concerning the issue of vaccines. The important thing is to make sure the public understands that there is no substantial risk from vaccines and that the benefits are very significant. Although I strongly believe in individual rights and the rights of parents to raise their children as they see fit, I also recognize that public health and public safety are extremely important in our society. Certain communicable diseases have been largely eradicated by immunization policies in this country. We should not allow those diseases to return by forgoing safety immunization programs for philosophical, religious, or other reasons when we have the means to eradicate them.4

“We already have policies in place at schools that require immunization records—this is a positive thing.”

Obviously, there are exceptional situations to virtually everything, and we must have a mechanism whereby those can be heard. Nevertheless, there is public policy and health policy that we must pay attention to regarding this matter. We already have policies in place at schools that require immunization records—this is a positive thing. Studies have shown over the course of time that the risk-benefit ratio for vaccination is grossly in favor of being vaccinated as opposed to not.5

There is no question that immunizations have been effective in eliminating diseases such as smallpox, which was devastating and lethal. When you have diseases that have been demonstrably curtailed or eradicated by immunization, why would you even think about not doing it? Certain people have discussed the possibility of potential health risks from vaccinations. I am not aware of scientific evidence of a direct correlation. I think there probably are people who may make a correlation where one does not exist, and that fear subsequently ignites, catches fire, and spreads. But it is important to educate the public about what evidence actually exists.6

I am very much in favor of parental rights for certain types of things. I am in favor of you and me having the freedom to drive a car. But do we have a right to drive without wearing our seatbelts? Do we have a right to text while we are driving? Studies have demonstrated that those are dangerous things to do, so it becomes a public-safety issue. You have to be able to distinguish our rights versus the rights of the society in which we live, because we are all in this thing together. We have to be cognizant of the other people around us, and we must always bear in mind the safety of the population. That is key, and that is one of the responsibilities of government.7

I am a small-government person, and I greatly oppose government intrusion into everything. Still, it is essential that we distinguish between those things that are important and those things that are just intruding upon our basic privacy. Whether to participate in childhood immunizations would be an individual choice if individuals were the only ones affected, but our children are part of our larger community. None of us lives in isolation. Your decision does not affect only you—it also affects your fellow Americans.8

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A CAUSEAND-EFFECT ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A CAUSEAND-EFFECT ARGUMENT

Carson’s title presents a strong thesis in favor of compulsory vaccination. Does Carson also state this thesis in the body of his essay? If so, where? If not, should he?

What is Carson’s opinion of those who request exemption from vaccination for religious reasons?

Carson is careful to stress the importance of “individual rights” (para. 4) and “parental rights” (7). Why does he do this? How do you think he expects his audience—readers of the conservative National Review— to react to this strategy? How do you know?

In paragraph 7, Carson draws analogies between mandatory vaccination laws and other public-safety laws. How convincing are these arguments? What other public-safety or public-health laws do you see as analogous to mandatory vaccination? Why?

The DailyBeast.com posted this article on January 30, 2014.

RUSSELL SAUNDERS

PEDIATRICIAN: VACCINATE YOUR KIDS—OR GET OUT OF MY OFFICE

If you won’t trust your doctors on vaccinating your kids, will you ever really trust them at all?1

If there is an issue more controversial and fraught with anger and frustration for pediatricians than the question of vaccine safety, I can’t think of it.2

Few topics are more apt to send my blood pressure skyrocketing than this. When the United Kingdom looks like sub-Saharan Africa in terms of wholly preventable disease outbreaks, something has gone terribly, tragically wrong.3

No contemporary phenomenon confounds and confuses me more than seemingly sensible people turning down one of the most unambiguously helpful interventions in the history of modern medicine.4

Yet they do.5

When parents of prospective patients come to visit my office to meet our providers and to decide if we’re the right practice for them, there are lots of things I make sure they know. I talk about the hospitals we’re affiliated with. I tell them when we’re open and how after-hours calls are handled. On my end, I like to know a bit about the child’s medical history, or if there are special concerns that expecting parents might have.6

And then this: I always ask if the children are vaccinated, or if the parents intend to vaccinate once the child is born. If the answer is no, I politely and respectfully tell them we won’t be the right fit. We don’t accept patients whose parents won’t vaccinate them.7

“We don’t accept patients whose parents won’t vaccinate them.”

It’s not simply that we think these beliefs are wrong. Declining vaccines is, at best, misguided. But of course those inclined to refuse them don’t agree with me, and I’m not going to try to change their minds. I’ve had too many of that kind of conversation over the years to hold out hope that anything I can say will sway them.8

Which is precisely the problem.9

There are few questions I can think of that have been asked and answered more thoroughly than the one about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines.10

The measles-mumps-rubella vaccine does not cause autism.11

The HPV vaccine is safe.12

There is no threat to public health from thimerosal.13

I can say all of this without hesitation because these concerns have been investigated and found to be groundless. But no amount of data seems sufficient to convince people who hold contrary beliefs.14

So then, if the entire apparatus of medical science has bent itself to the task of reassuring the public about the safety of vaccines and still comes up short in vaccine refusers’ estimation, how can I possibly rely on that apparatus to undergird conversations about other potentially fraught topics? If a conclusion as sound as the importance of immunizing your kids is suspect to them, what other conclusions may I rely upon?15

The physician-patient relationship, like so many other human relationships, requires an element of trust. I certainly neither want nor expect a return to the paternalistic “doctor knows best” mindset of bygone years, but I do need to know that patients’ parents respect my training and expertise. Refusing an intervention I desperately want all children to receive makes that respect untenably dubious.16

There will be times when parents and I may not see eye to eye, but not where I’m using the best evidence at hand to support my recommendations. Maybe they’ll want a test I think is useless, or want to use a supplement shown to be harmful. Perhaps it will be a referral for an intervention shown to have no benefit. If I can’t hope to persuade them by making reference to the available research, what can I expect to be for them other than a rubber stamp for their ideas? If medical science can’t answer the meritless qualms they have about vaccines, when can I use it at all?17

I have no doubt that these parents love their children immensely and are making what they believe to be the best decisions for them. I don’t dispute that. But any potential partnership we might create in caring for them together would rely on their belief that I have something other than a signature on an order form or prescription pad to offer.18

They must believe I have a perspective worth understanding.19

I often wonder why a parent who believes vaccines are harmful would want to bring their children to a medical doctor at all. After all, for immunizations to be as malign as their detractors claim, my colleagues and I would have to be staggeringly incompetent, negligent, or malicious to keep administering them.20

If vaccines caused the harms Jenny McCarthy and her ilk claim they do, then my persistence in giving them must say something horrifying about me. Why would you then want to bring your children to me when you’re worried about their illnesses? As a parent myself, I wouldn’t trust my children’s care to someone I secretly thought was a fool or a monster.21

It’s not merely that I don’t want to have to worry that the two-week-old infant in my waiting room is getting exposed to a potentially fatal case of pertussis if these parents bring their children in with a bad cough. It’s not just that I don’t want their kid to be the first case of epiglottitis I’ve ever seen in my career. Those are reasons enough, to be sure. But they’re not all.22

What breaks the deal is that I would never truly believe that these parents trust me. Giving kids vaccines is the absolute, unambiguous standard of care, as easy an answer as I will ever be able to offer.23

If they don’t trust me about that, how can I hope they would if the questions ever got harder?24

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A CAUSEAND-EFFECT ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A CAUSEAND-EFFECT ARGUMENT

Like Ben Carson (p. 502) and Jeffrey Singer (p. 507), Saunders is a medical doctor. How does his professional experience influence the type of argument he makes?

In one sentence, paraphrase Saunders’s thesis. Does this thesis appear in the essay? If so, where? If not, does its absence weaken Saunders’s argument? Why or why not?

Saunders says that the issue under discussion makes his blood pressure rise and notes that the issue “confounds and confuses” him (paras. 3 and 4). Where else do his emotions come through? Do these emotional statements increase or decrease his credibility? Explain.