Structuring a Definition Argument

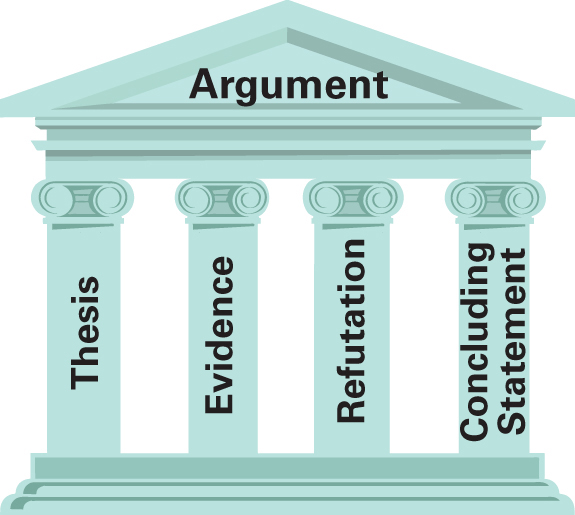

In general terms, a definition argument can be structured as follows:

Introduction: Establishes a context for the argument by explaining the need for defining the term; presents the essay’s thesis

Evidence (first point in support of thesis): Provides a short definition of the term as well as an extended definition (if necessary)

Evidence (second point in support of thesis): Shows how the term does or does not fit the definition

Refutation of opposing arguments: Addresses questions about or objections to the definition; considers and rejects other possible meanings (if any)

Conclusion: Reinforces the main point of the argument; includes a strong concluding statement

![]() The following student essay includes all the elements of a definition argument. The student who wrote this essay is trying to convince his university that he is a nontraditional student and is therefore entitled to the benefits such students receive.

The following student essay includes all the elements of a definition argument. The student who wrote this essay is trying to convince his university that he is a nontraditional student and is therefore entitled to the benefits such students receive.

GRAMMAR IN CONTEXT

Avoiding Is Where and Is When

In a formal definition, you may find yourself using the phrase is where or is when. If so, your definition is incomplete because it omits the term’s class. The use of is where or is when signals that you are giving an example of the term, not a definition. You can avoid this problem by making sure that the verb be in your definition is always followed by a noun.

| INCORRECT | The university website says that a nontraditional student is when you live off campus, commute from home, have children, are a veteran, or are over the age of twenty-five. |

| CORRECT | The university website says that a nontraditional student is someone who lives off campus, commutes from home, has children, is a veteran, or is over the age of twenty-five. |

EXERCISE 12.3

EXERCISE 12.3

The following essay, “Athlete vs. Role Model” by Ej Garr, includes the basic elements of a definition argument. Read the essay, and then answer the questions that follow it, consulting the outline on page 422 if necessary.

This blog post first appeared on August 31, 2014, in the Lifestyle section of newshub.com.

EJ GARR

ATHLETE VS. ROLE MODEL

Expectations of professional athletes have become such a touchy subject over the years, and deciphering what defines a role model has become an even darker subject.1

Kids who are into sports tend to look up to a favorite player or team and find someone they say they want to be like when they grow up. Unfortunately, athletes today are not what they were decades ago when a paycheck was not the sole reason they wanted an athletic career.2

Take Roger Staubach or Bart Starr for example. Both have multiple Super Bowl titles. Both had tremendous NFL careers, and both conducted themselves in public with class and dignity. They deserved every accolade they received, both personally and professionally. Starr and his wife co-founded the Rawhide Boys Ranch, which helps kids who are in need of proper direction and might not have the family resources that can make a kid’s life easier.3

Roger Staubach was a class act, served in our Navy, and is a Vietnam vet. These are just two examples of players who gained role model status because of how they acted and what they contributed, not simply because they played in the NFL, earned a big paycheck. People rooted for them and looked up to them. Kids wanted to be like them. There were absolutely no discouraging words said about them from anyone who has ever met them. They had class, caring, and concern for other people, both on the field and off.4

It is easy for kids, who hear about their favorite athlete who signed a multi-million dollar contract, to say to themselves, “I wish I could do that.” Do what? Become a pro or make lots of money? What about becoming a better person? What about giving back?5

Many athletes do not think about how to be a better role model to those kids that look up them, how to make their community better, or what they can “give back” to the less fortunate.6

Think back to Pete Rose, who was an amazing ballplayer when he was on the field, but all he is known for today is gambling when he became a manager and being banned for life from baseball and the Hall of Fame. Pete Rose was a role model for every kid in his generation when he played baseball. Ran hard to first on a simple walk and gave every ounce of his being to the game. Then, that all went out the window and the role model moniker was gone faster than you could shake your head at what he did. He didn’t think of those kids who looked up to him.7

Then there’s Ray Rice, who was on the cusp of being a role model with a Super Bowl trophy in tow with the Baltimore Ravens. Kids looked up to him. Instead, he was caught on video dragging his unconscious wife out of an elevator after she “accidentally” put her face in front of his fist.8

And who can ever forget Michael Vick, who went to prison on dog fighting charges and arranging a death sentence for animals. It has been documented that he even placed a bet or two on those fights! Just recently, although not as criminally serious, USC’s Josh Shaw lied about an injury that he claimed to receive when he rescued his nephew. He finally admitted he fabricated the story and all the facts are not out yet, but he went from a potential role model to a hero and then to a zero in record time. These guys sure aren’t thinking about the kids who look up to them and want to be like them.9

These days, sports newscasts are chock-filled with reports of pro athletes using performance enhancing drugs. Over the years there’s been Lance Armstrong, Alex Rodriguez, Jose Canseco, Shawne Merriman, Barry Bonds, and even gold medalist Marion Jones. It is well-documented that Alex Rodriguez spent a lot of money buying performance enhancing drugs, rather than becoming a hard-working baseball player and using his money for good. Alex Rodriguez is only worried about Alex Rodriguez. That, unfortunately, is the ego that many athletes have today. I am me, you are you, and I can do what I want. And who cares if you’re watching what I’m doing and looking up to me.10

No sir! Athletes like this are arrogant and act like idiots, carrying guns, hitting spouses, and taking drugs which are all, by the way … ILLEGAL in this country! Our world needs more role models like Staubach and Starr and less arrogant athletes who think society owes them something simply because they make big money and live in a big house and drive a nice car.11

Professional athletes are not born role models. They are getting paid to play a game. That far from constitutes the making of a role model. Perhaps this mentality of being better than anyone else starts at the college level. Even the NCAA has acknowledged that bringing in athletes to fill the stands is more important than making sure they get a quality education, because 75% of the athletes who play in college basketball or football are simply there to play their two years and move on to collect a big fat paycheck in the pros. Are they taught anything about giving back and setting a positive example?12

“Will that make kids look up to you?”

A role model comes not from being an athlete and collecting that big paycheck, but for what you do with and in your life. Throw a football and score three touchdowns today? Hey, good for you man. You will make the headlines, be highlighted on ESPN, and the press will come calling. Will that make kids look up to you? Sure it will, you won the game and had a great day, good for you. But you’re not a role model.13

Do you know why Derek Jeter, Drew Brees, and Tom Brady are true role models? It’s about how they carry themselves on and off the field. It’s about how Jeter, during his rookie year in 1996, achieved his goal of establishing the Turn 2 Foundation, where he gives back and helps kids who are less fortunate. That is a role model! And Drew Brees is a great family man who gives of his time. Here, let me break it down for you. “Brittany and Drew Brees, and the Brees Dream Foundation, have collectively committed and/or contributed just over $20,000,000 to charitable causes and academic institutions in the New Orleans, San Diego and West Lafayette/Purdue communities.”14

He didn’t buy his way into being a role model. He simply cares about the people who he knows have supported him in his career.15

Tom Brady has a beautiful supermodel wife and many guys are saying, “I wish I was Tom Brady so I could be married to a supermodel and win Super Bowls.” That doesn’t make him a role model. It’s because he is a class act who does a ton for the Boys and Girls Clubs of America and gives his time and money to help others.16

I have the pleasure of hosting a radio show called Sports Palooza Radio on Blogtalkradio. My wife and I interview professional athletes every Thursday on our two-hour show. Do you know what one of the biggest things is that we look for when we are booking guests? It’s what the athlete does to make someone else’s life a bit easier. Not everyone has it easy and gets spoon fed money and material things in life. That’s who kids should be looking up to.17

There are former NFLers Dennis McKinnon and Lem Barney, who work tirelessly with Gridiron Greats to help former football players. There’s former New York Mets Ed Hearn, who is fighting his own health battle, but works with the NephCure Foundation and his own Bottom of the 9th Foundation. There’s Roy Smalley, who is president of the Pitch in for Baseball foundation, an organization that collects baseball gear for children who don’t have access to others. NFLer Calais Campbell has his own foundation and works hard to help others as well. There are so many other positive examples of athletes doing good things, but they aren’t making the headlines. Those athletes are role models.18

And then there’s Donald Driver. He didn’t start out as role model material. In his book, Driven, he tells the story of his rough childhood where he sold drugs to make money and carried guns. But he cleaned up his act and became a stellar NFL superstar, carrying himself with class and dignity. He is founder of the Donald Driver Foundation and the recipient of the 2013 AMVETS Humanitarian of the Year. If a kid looks up to him it’s because he shows them how to overcome and persevere. That’s a role model.19

Don’t expect the athletes of today to be instant role models. Instantly famous? Maybe that is a better description, but an athlete needs to earn the role model status. That honor is not bestowed on you because you cashed a nice paycheck for playing a game!20

Identifying the Elements of a Definition Argument

- In your own words, summarize the essay’s thesis.

This essay does not include a formal definition of role model. Why not? Following the template below, write your own one-sentence definition of role model.

A role model is a ________________________ who _______________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________.- Throughout this essay, Garr gives examples of athletes who are and who are not role models. What does he accomplish with this strategy?

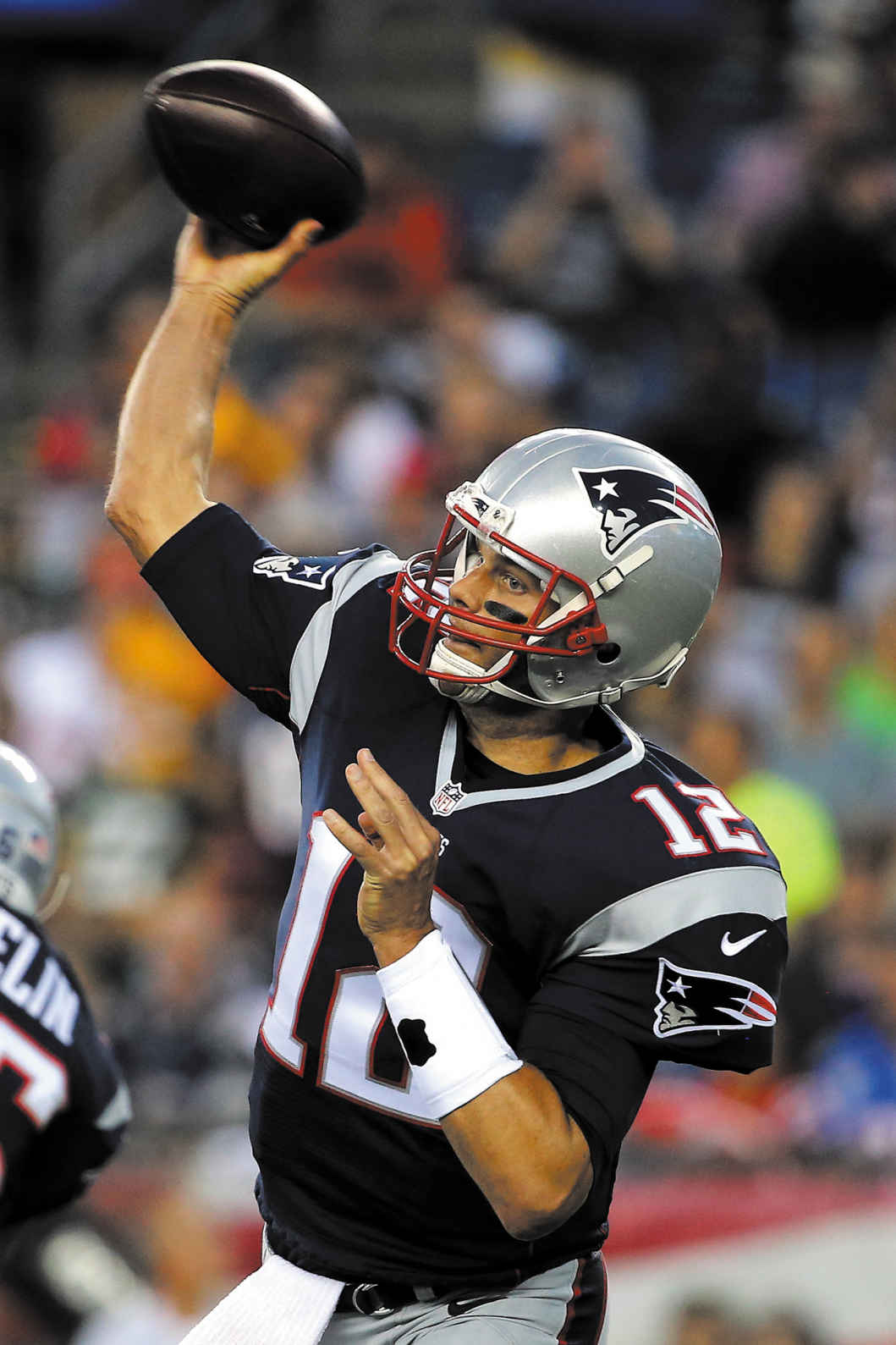

- In paragraph 16, Garr discusses why Tom Brady, quarterback for the NFL’s New England Patriots, is a role model. Since this article was written, Brady was accused of deflating footballs during the 2015 Super Bowl to give his team an unfair advantage. Although Brady denied the charges, the NFL gave him a four-game suspension. Does this scandal disqualify him from being a role model? Does Brady’s scandal rise to the level of those involving Pete Rose, Ray Rice, and Michael Vick? Why or why not?

- Where in the essay does Garr define the term role model by telling what it is not? What does Garr accomplish with this strategy?

- Where does Garr introduce possible objections to his idea of a role model? Does he refute these objections convincingly? If not, how should he have addressed them?

- In paragraph 17, Garr says that he and his wife host a radio show. Why does he mention this fact?

Tom Brady, a quarterback for the New England Patriots.

Maddie Meyer/Getty Images

EXERCISE 12.4

EXERCISE 12.4

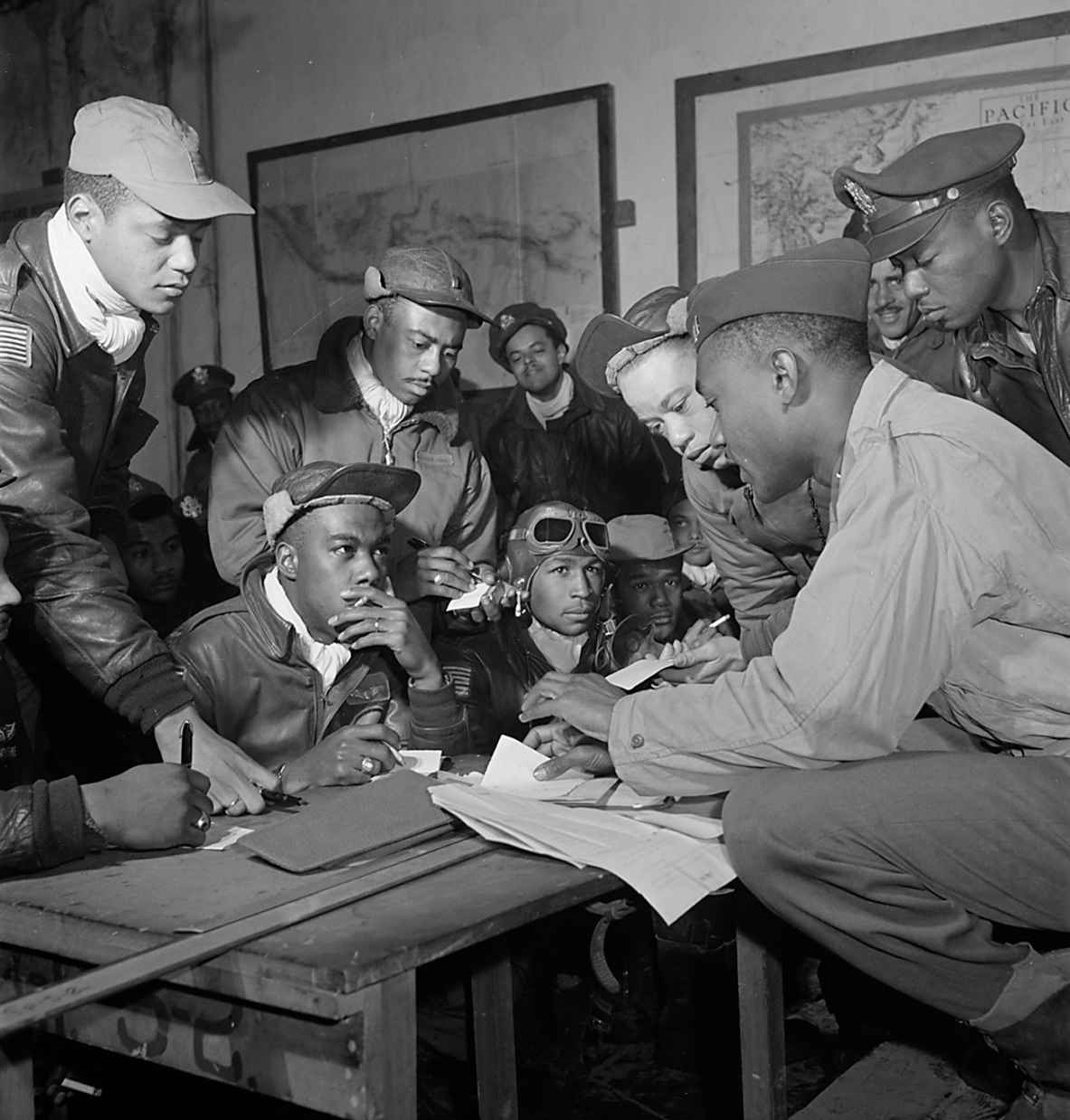

According to former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, “We gain strength, and courage, and confidence by each experience in which we really stop to look fear in the face…. We must do that which we think we cannot.” Each of the two pictures on the facing page presents a visual definition of courage. Study the pictures, and then write a paragraph in which you argue that they are (or are not) consistent with Roosevelt’s concept of courage.

Firefighters at Ground Zero after the World Trade Center terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, in New York City

New York Daily News Archive/Getty Images

The Tuskegee Airmen, a group of African-American men who overcame tremendous odds to become U.S. Army pilots during World War II

Toni Frissell Collection, Library of Congress

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

Is Wikipedia a Legitimate Research Source?

© Fabian Bimmer/dpa/Corbis

Go back to page 417 and reread the At Issue box, which gives some background on the question of whether Wikipedia is a legitimate research source. As the following sources illustrate, this question suggests a variety of possible responses.

As you read the sources that follow, you will be asked to answer some questions and to complete some simple activities. This work will help you understand both the content and the structure of the sources. When you are finished, you will be ready to write a definition argument on the topic, “Is Wikipedia a Legitimate Research Source?”

SOURCES

Timothy Messer-Kruse, “The ‘Undue Weight’ of Truth on Wikipedia,” p. 433

Timothy Messer-Kruse, “The ‘Undue Weight’ of Truth on Wikipedia,” p. 433 Michael Martinez, “Why Citations Do Not Make Wikipedia and Similar Sites Credible,” p. 436

Michael Martinez, “Why Citations Do Not Make Wikipedia and Similar Sites Credible,” p. 436 Kevin Morris, “After a Half-Decade, Massive Wikipedia Hoax Finally Exposed,” p. 443

Kevin Morris, “After a Half-Decade, Massive Wikipedia Hoax Finally Exposed,” p. 443 Alison Hudson, “Stop Wikipedia Shaming,” p. 446

Alison Hudson, “Stop Wikipedia Shaming,” p. 446 Andreas Kolbe, “Debunking the ‘Accurate as Britannica ’ Myth,” p. 450

Andreas Kolbe, “Debunking the ‘Accurate as Britannica ’ Myth,” p. 450 Randall Stross, “Anonymous Source Is Not the Same as Open Source,” p. 453

Randall Stross, “Anonymous Source Is Not the Same as Open Source,” p. 453 Wikipedia, “Wikipedia: About,” p. 457; Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “About the IEP,” p. 458

Wikipedia, “Wikipedia: About,” p. 457; Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “About the IEP,” p. 458 Neil Waters, “Wikiphobia: The Latest in Open Source,” p. 461

Neil Waters, “Wikiphobia: The Latest in Open Source,” p. 461

This essay was published on February 12, 2012, in the Chronicle Review.

TIMOTHY MESSER-KRUSE

THE “UNDUE WEIGHT” OF TRUTH ON WIKIPEDIA

For the past 10 years I’ve immersed myself in the details of one of the most famous events in American labor history, the Haymarket riot and trial of 1886. Along the way I’ve written two books and a couple of articles about the episode. In some circles that affords me a presumption of expertise on the subject. Not, however, on Wikipedia.1

The bomb thrown during an anarchist rally in Chicago sparked America’s first Red Scare, a high-profile show trial, and a worldwide clemency movement for the seven condemned men. Today the martyrs’ graves are a national historic site, the location of the bombing is marked by a public sculpture, and the event is recounted in most American history textbooks. Its Wikipedia entry is detailed and elaborate.2

A couple of years ago, on a slow day at the office, I decided to experiment with editing one particularly misleading assertion chiseled into the Wikipedia article. The description of the trial stated, “The prosecution, led by Julius Grinnell, did not offer evidence connecting any of the defendants with the bombing….”3

Coincidentally, that is the claim that initially hooked me on the topic. In 2001 I was teaching a labor-history course, and our textbook contained nearly the same wording that appeared on Wikipedia. One of my students raised her hand: “If the trial went on for six weeks and no evidence was presented, what did they talk about all those days?” I’ve been working to answer her question ever since.4

I have not resolved all the mysteries that surround the bombing, but I have dug deeply enough to be sure that the claim that the trial was bereft of evidence is flatly wrong. One hundred and eighteen witnesses were called to testify, many of them unindicted coconspirators who detailed secret meetings where plans to attack police stations were mapped out, coded messages were placed in radical newspapers, and bombs were assembled in one of the defendants’ rooms.5

In what was one of the first uses of forensic chemistry in an American courtroom, the city’s foremost chemists showed that the metallurgical profile of a bomb found in one of the anarchists’ homes was unlike any commercial metal but was similar in composition to a piece of shrapnel cut from the body of a slain police officer. So overwhelming was the evidence against one of the defendants that his lawyers even admitted that their client spent the afternoon before the Haymarket rally building bombs, arguing that he was acting in self-defense.6

So I removed the line about there being “no evidence” and provided a full explanation in Wikipedia ’s behind-the-scenes editing log. Within minutes my changes were reversed. The explanation: “You must provide reliable sources for your assertions to make changes along these lines to the article.”7

That was curious, as I had cited the documents that proved my point, including verbatim testimony from the trial published online by the Library of Congress. I also noted one of my own peer-reviewed articles. One of the people who had assumed the role of keeper of this bit of history for Wikipedia quoted the Web site’s “undue weight” policy, which states that “articles should not give minority views as much or as detailed a description as more popular views.” He then scolded me. “You should not delete information supported by the majority of sources to replace it with a minority view.”8

“‘You should not delete information supported by the majority of sources to replace it with a minority view.’”

The “undue weight” policy posed a problem. Scholars have been publishing the same ideas about the Haymarket case for more than a century. The last published bibliography of titles on the subject has 1,530 entries.9

“Explain to me, then, how a ‘minority’ source with facts on its side would ever appear against a wrong ‘majority’ one?” I asked the Wiki-gatekeeper. He responded, “You’re more than welcome to discuss reliable sources here, that’s what the talk page is for. However, you might want to have a quick look at Wikipedia ’s civility policy.”10

I tried to edit the page again. Within 10 seconds I was informed that my citations to the primary documents were insufficient, as Wikipedia requires its contributors to rely on secondary sources, or, as my critic informed me, “published books.” Another editor cheerfully tutored me in what this means: “Wikipedia is not ‘truth,’ Wikipedia is ‘verifiability’ of reliable sources. Hence, if most secondary sources which are taken as reliable happen to repeat a flawed account or description of something, Wikipedia will echo that.”11

Tempted to win simply through sheer tenacity, I edited the page again. My triumph was even more fleeting than before. Within seconds the page was changed back. The reason: “reverting possible vandalism.” Fearing that I would forever have to wear the scarlet letter of Wikipedia vandal, I relented but noted with some consolation that in the wake of my protest, the editors made a slight gesture of reconciliation—they added the word “credible” so that it now read, “The prosecution, led by Julius Grinnell, did not offer credible evidence connecting any of the defendants with the bombing….” Though that was still inaccurate, I decided not to attempt to correct the entry again until I could clear the hurdles my anonymous interlocutors had set before me.12

So I waited two years, until my book on the trial was published. “Now, at last, I have a proper Wikipedia leg to stand on,” I thought as I opened the page and found at least a dozen statements that were factual errors, including some that contradicted their own cited sources. I found myself hesitant to write, eerily aware that the self-deputized protectors of the page were reading over my shoulder, itching to revert my edits and tutor me in Wiki-decorum. I made a small edit, testing the waters.13

My improvement lasted five minutes before a Wiki-cop scolded me, “I hope you will familiarize yourself with some of Wikipedia ’s policies, such as verifiability and undue weight. If all historians save one say that the sky was green in 1888, our policies require that we write ‘Most historians write that the sky was green, but one says the sky was blue.’ … As individual editors, we’re not in the business of weighing claims, just reporting what reliable sources write.”14

I guess this gives me a glimmer of hope that someday, perhaps before another century goes by, enough of my fellow scholars will adopt my views that I can change that Wikipedia entry. Until then I will have to continue to shout that the sky was blue.15

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

- Throughout most of his essay, Messer-Kruse makes an appeal to ethos. What is this appeal? How does it strengthen his argument?

- What misconception in the “Haymarket Affair” entry did Messer-Kruse try to correct? What changes did he make? What documents did he cite to support these changes?

- What is Wikipedia ’s “undue weight” policy? How did this policy cause the Wikipedia gatekeeper to reject Messer-Kruse’s changes? What did the editor mean when he said, “Wikipedia is not ‘truth,’ Wikipedia is ‘verifiability’ of reliable sources” (para. 11)?

- Do you think that Messer-Kruse’s complaints about Wikipedia have merit, or do you think that the Wikipedia editors were right to reject his changes? Explain.

- In a response to Messer-Kruse’s article, one person posted the following:

On the Internet, no one knows that your [sic] a professor. If you’re used to deferential treatment, at your home institution, you’ll be treated like anyone else in the Wide Open Internet. This skepticism is a good thing—after all, some prankster could easily create an account using your name and pretend to be you.

Do you think this statement points out Wikipedia ’s strengths or its weaknesses? Explain.

- How do you think Randall Stross (p. 453) would respond to Messer-Kruse’s essay?

This post first appeared on Michael Martinez’s blog, SEO Theory, on June 22, 2014.

MICHAEL MARTINEZ

WHY CITATIONS DO NOT MAKE WIKIPEDIA AND SIMILAR SITES CREDIBLE

If you search Twitter for word combinations like “Wikipedia credible” you may find people arguing back and forth about how credible the site is as a source of information. I even found a Tweet where someone wrote: “I hate when people say Wikipedia isn’t a credible source. You click on the links on the page which lead to credible sources.” That’s very true. Many (though not all) Wikipedia articles link out to “credible sources” but there are several reasons why providing citations doesn’t make you instantly credible. This is true for everyone; it’s not something that is peculiar to Wikipedia.1

And then there are reasons why Wikipedia is not and never can be a credible source of information. So let me deal with these two very different explanations separately. But first, let’s talk about credibility.2

“But first, let’s talk about credibility.”

Credible Information Is Not Always Reliable

History is filled with grave mistakes that were committed on the basis of credible information. The interpretations of the credible information may not always be universally supported; and not everyone will agree that information is credible. Nonetheless, information may be presented as credible by a credible (or authoritative) person.3

For example, during World War II both the Axis and the Allies used extensive networks of spies supported by intelligence agencies with all the latest technology and encryption/decryption skills to study each other’s forces and strategies, report back, and analyze enemy intentions. Knowing that both sides were doing this, both sides in the war resorted to disseminating false information.4

As it turns out the Allies proved to be more successful during critical operations. The United States’ use of Navajo “Wind-talkers” confounded Japanese intelligence. While preparing for the D-Day invasion of northern France General Eisenhower deployed a false army under the command of General Patton to mislead the Germans about Allied intentions. In at least one airdrop operation dummies on parachutes were dropped out of plans to fool German gunners and inflate the numbers of attacking soldiers being reported to headquarters.5

The Axis soldiers and spies charged with collecting and reporting this information were generally credible sources of information. They just didn’t pass on reliable information. Credibility doesn’t make you accurate or correct.6

To be credible, a source is convincing. It may be convincing on the basis of past interaction (such as an undercover police officer who has conducted numerous successful investigations). It may be convincing on the basis of logic (organizing facts in as complete and supportable manner as possible). It may also be convincing due to a lack of alternative or contradictory information.7

In many UFO investigations police officers are often deemed to be highly credible sources of information. However, police witnesses do not always recognize what they are describing. In fact, we don’t investigate Unidentified Flying Objects unless we have reason to believe they are hostile. So just because a police officer credibly reports a UFO doesn’t mean that any claims of extraterrestrial visitation on the basis of that report are valid.8

Credibility in reporting source does not necessarily confer validity upon any conclusions drawn on the basis of the reported information. Hence, credibility of source in itself is not a persuasive argument for believing something. And that is especially true when you need to establish provable facts. So being credible is no guarantee of being a reliable source of good or useful information.9

Why Providing Citations Is Not Enough to Make You Reliable

Whether you write a huge long article or a very short quote, if you are relaying information you found elsewhere on the Web it is courteous to provide a citation of your source. Pointing people to your source discredits any allegation that you made up what you are sharing.10

Nonetheless, even if you publish 1,000,000 articles that all include citations for sources, your credibility depends on more than the credibility of your sources. If your credible sources are wrong, for example, then your use of those sources undermines your credibility. And credible sources can be very, very wrong.11

Here is an article from 2005 that was published in the Harvard [Men’s Health Watch]: “Help for Your Cholesterol When the Statins Won’t Do.” The article includes the following information:12

… 3%–4% of people […] don’t do well with a statin drug. In a few cases, the drugs simply don’t work, but more often the reason is a side effect. The most common statin toxicity is liver inflammation. Most patients with the problem don’t even know they have it, but some develop abdominal distress, loss of appetite, or other symptoms. Even without these complaints, liver enzyme abnormalities, such as high aminotransferase levels, show up in the blood tests of 1%–2% of people taking a statin drug. The other major side effect is muscle inflammation, which can be silent or cause cramps, fatigue, or heavy, aching muscles.

At the time this article was published the information was deemed highly credible, even correct, based on the science available at the time. Unfortunately for millions of statin patients worldwide, the research was highly flawed. We now know that 37.5% of clinical trial patients could not tolerate statins.

Also, based on patient feedback over the past 9 years, most medical resources now show that muscle problems are the most common side effect. When the Harvard [Men’s Health Watch] publishes horribly wrong information about a widely used class of medicines, people should sit up and take notice. To their credit, doctors at Harvard University have come out this year in strong opposition to the use of statins for patients who have not had a cardiovascular event. Recent research shows very convincingly that there is 0 benefit for 80% of people with high cholesterol from taking statins. Only people who have already suffered a heart attack or other CVE may benefit from use of statins.13

Credible information can therefore be wrong enough that even citing it is not useful. Basing any article on a citation of a credible source that has been discredited in topical context means you are reporting wrong information, and therefore your article is not credible. So what if the 2005 article was once deemed correct? We now know it to be wrong; therefore using it as a source of information for any current survey of medical practice is inappropriate.14

You can provide all the citations to credible sources you wish, but if they are wrong then your own credibility may not suffer because you use credible sources but your information is unreliable.15

The key takeaway here is that just because information is credible does not mean it is accurate, correct, or reliable.16

Why Accurate Citations Do Not Make You Reliable

So let’s say you go the extra mile and do your research so well that you not only compile credible sources of information you also find independent confirmation of the claims those sources make. Your sources’ credibility is impeccable and the information they present does not appear to be contradicted by any other credible points of view. There are still potential pitfalls you have to overcome.17

Less Credible Sources May Be More Correct Sometimes people who are hard to believe really do get the facts straight. Maybe they are being intuitive. Maybe they lack any scientific proof. Maybe there is no way to confirm what they are saying. These deficiencies in support context do not make a viewpoint wrong any more than hundreds of supporting contexts make a viewpoint right.18

The Correct Information May Not Yet Be Known Sometimes everyone latches on to the same plausible explanation for lack of anything better. This even happens in science, especially in theoretical science where independent observations and experiments have not yet shown a theory to be true (or as true as we can confirm it to be given our current state of knowledge). Scientists will tell you that Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity is true because it has been proven so by many experiments. They’ll also point out that we have spent billions of dollars on experiments that attempt to prove the theory false. Although no one expects that to happen we would be practicing poor science by neglecting to attack and challenge the theory from every conceivable angle.19

We may never fully know if Einstein was wrong.20

Truth is not democratically determined. It doesn’t matter how many sources report the same information, even if they all arrived at their conclusions independently of each Wikipedia other. They can still be wrong. They maybe wrong. In any given topic you have to allow for the possibility that some new verifiable evidence will eventually turn the entire world upside down.21

Credible Sources May Be Corrupt Whether you are dealing with a police officer who has turned to crime, a scientist who is falsifying data, or a reporter who just makes up a false story sometimes your credible source is actively trying to deceive you. You can’t trust anyone. Literally.22

Credible Sources May Have Been Deceived As noted above, credible sources of information were misled by counter-intelligence operations during World War II. More recently, former U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell presented the U.S.’s case for invading Iraq to the United Nations. His argument was based on two points: Saddam Hussein refused to allow UN Weapons Inspectors back into Iraq to verify that all his weapons of mass destruction (and the capability to make more) had been destroyed; and the U.S. had intelligence that led government analysts to conclude there was a high probability that Saddam Hussein was hiding something (probably Weapons of Mass Destruction).23

Secretary Powell was viewed by everyone as a very credible, sincere man who would not intentionally mislead anyone. He was a very credible source. He just didn’t have very good information. After we invaded Iraq our forces did find several hundred chemical warheads that had been falsely reported as destroyed years before. WMD experts dismissed these warheads as being so old their chemicals would be inert. The military destroyed the warheads with all safety protocols just in case.24

So as it turned out Saddam Hussein did not have a functioning WMD program or even a viable cache of weapons. But no one knew that at the time because some of the intelligence given to Secretary Powell was false. Someone lied and the lies were passed on.25

“Someone lied and the lies were passed on.”

The key takeaway here is that lies often get fed into the information chain and they are passed around. Viral propaganda theory tells us that it doesn’t matter if information is true or false: people will accept it if the source is credible, and once they believe a certain point of view it becomes next to impossible to change their minds.26

Why Your Beliefs May Make You Unreliable

You may have the most credible sources of information to hand. You may have eliminated all relevant doubt. You may have clear-cut scientific proof that shows no one has lied in the chain of information leading up to your own presentation. And yet your own article may be unreliable. Why? Because you believe.27

As I pointed out above, viral propaganda theory shows us that people are reluctant to change their minds. Just because I come along and point out all the fallacies of the viewpoint that you believe to be true doesn’t mean you’re going to question what you have believed again. You have already questioned that viewpoint and challenged it according to your prior knowledge and beliefs and it has passed all your tests.28

To change your mind now would be to admit you were wrong and most people hate to admit they are wrong. In fact, recent research suggests that people don’t easily stop believing false information. Conviction is most likely a hard-wired trait in our behavior. My guess is that we need it in order to survive challenging times. If you don’t believe you’ll “get through this” then you may give up and die.29

But if that is correct then conviction (or self-imposed belief) is irrational and irrational behavior cannot easily be changed. The same factors that contribute to stubbornness when you’re trying to survive also contribute to your pig-headedness when you’re flat out wrong.30

So when you prepare an article on any topic (and this is equally true of me), you will write to support your belief and to undermine any doubts or challenges to your belief. You may have persuasive arguments to shoot down all objections to the points you make but it is easy to find examples of compelling arguments that rely in part on errors of omission. Intentionally (or even subconsciously) omitting relevant information changes the degree of completeness of your argument. In fact, errors of omission are often used to strengthen arguments.31

Omitting inconvenient facts and points of view makes you an unreliable source of information, even if the omissions make your arguments more persuasive and compelling. You may omit something merely because you couldn’t think of everything you should have mentioned, or because you sincerely believe what you are omitting is not worthy of inclusion. Nonetheless, you can easily paint an incomplete (and therefore inaccurate) picture.32

But many people turn to errors of omission as a way of winning arguments. If they present only the facts that support their own points of view they can score points and change minds. It’s easier to win people to your cause by omitting relevant information than by pointing out that the other guy left something out.33

You may also lend more credence to sources you trust than to sources you trust less. Hence, you introduce a bias into your presentation by saying things like “Dubious Dave has shown conclusively that frogs leap 15 feet backwards” and “Scientific Sam argues with Dubious Dave but has yet to provide a compelling argument” and “Silly Sally has challenged Scientific Sam several times.”34

The key takeaway here is that people favor the viewpoint they believe and tend to treat opposing viewpoints unfairly. To do otherwise might force them to admit they were wrong.35

And So Wikipedia Introduces More Problems

In addition to all the problems listed above, Wikipedia has its own peculiar set of issues that make its well-cited articles unreliable.36

Poor writing is the worst aspect of Wikipedia. The English-language Website’s content is a spaghetti-weave of mismatched idiom, much of it written by non-native English writers. But even among the native English writers there are regional variations in word choices and colloquial expressions.37

Poor internal annotation is another grave problem with Wikipedia. It provides no mechanism for explaining idiomatic expressions, unless those expressions are notable enough to have their own articles (but even then many marked up articles do not exist and so explanations are lacking). Use of unexplained idiom makes it hard for the average reader to understand what a given contributor is trying to say or whether other contributors agree with him.38

Wikipedia ’s conflict resolution system always favors the biased reverter. Whenever someone tries to correct a Wikipedia article, the first person to revert that change will win any reversion war because Wikipedia rules don’t allow the person who made the change to make the last reversion. All disputes must be left up to the community to decide, and there you are asking in-competent people to decide between two opposing points of view, one of which almost certainly has more experience in Wikipedia ’s in-site debates than the other.39

Wikipedia ’s rules for citation also don’t require that a proper context be provided. For example, you could write “Michael Martinez says that SEO is not all about links” or you could write “Michael Martinez opposes link-based SEO strategies” and then provide a numbered citation that links to an SEO Theory article like “How Best to Use Links for SEO” (where I do in fact say “SEO is not all about links” but go on to show you how to use links in all sorts of SEO).40

In this example you can write something completely misleading simply by omitting proper context: “Martinez disagrees with SEOs who rely on links.” Most readers will not check the citation so they will never know that I actually show people how to use links in SEO.41

Wikipedia further instructs contributors not to use blogs as credible sources. Many articles use blogs anyway but sometimes blogs are the only sources of information on a topic. Worse, many news articles cite very unreliable people as sources of information (for many of the reasons given above). In the world of ignorant people the self-confident man is king, no matter how wrong he is. We see that in Internet marketing all the time, not to mention politics and government.42

Finally, Wikipedia ’s content may change at any given time. How credible would you think your neighbor if this morning he tells you it’s June 2 and in the afternoon says June 3 and in the evening changes his mind back to June 2? Would you want to be treated by a doctor who says today, “You have high cholesterol,” tomorrow “your cholesterol is fine,” and two weeks from today says “dubious studies suggest that statistically your cholesterol will fall somewhere inside the marginal zone because you eat butter”?43

Wikipedia, other Wiki sites, and indeed all crowd-sourced Websites are fundamentally and inherently UNcredible. They lack credibility because they can be changed, not because of whatever they say today.44

A credible source of information is consistent. An incredible source of information is unpredictable.45

A credible source of information may be reliable or it may be unreliable.46

In fact, it doesn’t matter how credible Wikipedia seems to you or me, it is truly an unreliable source of information simply because there is no way that any of us can ensure that its information is accurate, reliable, correct, or complete.47

All the citations in the world won’t change that.48

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

- Martinez devotes most of his essay to defining credibility. Should he have spent more time discussing Wikipedia? Why or why not?

- What does Martinez mean when he says “just because information is credible does not mean it is accurate, correct, or reliable” (para. 16)? What distinction does he make between credible information and reliable information?

- What specific objections does Martinez have to Wikipedia? Why does he think that the problems he mentions make Wikipedia (and all crowd-sourced sites) an unreliable source of information?

- Is Martinez’s essay organized deductively or inductively? What are the advantages and disadvantages of this organization?

- Given Martinez’s guidelines, what kind of information in an encyclopedia entry is credible? What kind of information can never be credible?

- Martinez does not address opposing arguments. Would his argument have been stronger had he done so? Explain.

Morris’s article appeared online at DailyDot.com on January 1, 2013.

KEVIN MORRIS

AFTER A HALF-DECADE, MASSIVE WIKIPEDIA HOAX FINALLY EXPOSED

Up until a week ago, here is something you could have learned from Wikipedia:1

From 1640 to 1641 the might of colonial Portugal clashed with India’s massive Maratha Empire in an undeclared war that would later be known as the Bicholim Conflict. Named after the northern Indian region where most of the fighting took place, the conflict ended with a peace treaty that would later help cement Goa as an independent Indian state.2

Except none of this ever actually happened. The Bicholim Conflict is a figment of a creative Wikipedian’s imagination. It’s a huge, laborious, 4,500 word hoax. And it fooled Wikipedia editors for more than 5 years.3

“Except none of this ever actually happened.”

But even exposed and deleted, Wikipedia ’s influence over the Web is such that the Bicholim Conflict continues to persist, like a resilient parasite.4

The perpetrator of the hoax is a mystery. Wikipedia admins deleted the edit history along with the article. Users of the Wikipediocracy forum have pinned down a likely suspect, however, a Wikipedian who went by the handle “A-b-a-a-a-a-a-a-b-a.” He or she authored a big chunk of the article’s text, and also nominated it for “Featured Article” standing in October 2007, writing:5

I’m nominating this article for featured article because after much work I believe it has reached its maximum potential. It is not a very huge event and doesn’t have more than a few chapters in literature based on it but I’ve still created the article to quite a good size.

“Featured Article” status is a bit of a badge of honor on Wikipedia, a recognition bestowed to only the highest quality pieces on the site. Out of more than4 million English Wikipedia articles, only 3,772 are “featured.” Thankfully the Bicholim Conflict didn’t pass muster—editors who reviewed it cited an overreliance on a few weak sources, never realizing that those sources never existed in the first place.

And the Bicholim Conflict was still labeled a “Good Article,” a status it had received just two months after being created in July, 2007. That status is a step down from featured, but still a designation given to less than 1 percent of all English-language articles on the site.6

Enter Wikipedian-detective ShelfSkewed, who decided in late December, for no apparent reason, to delve into the article’s sources. What he found was pretty amazing: None of the books used as source material in the article appeared to exist.7

On Dec. 29, 2012, ShelfSkewed nominated the whole thing for deletion:8

After careful consideration and some research, I have come to the conclusion that this article is a hoax—a clever and elaborate hoax, but a hoax nonetheless. An online search for “Bicholim conflict” or for many of the article’s purported sources produces only results that can be traced back to the article itself. Take, for example, one of the article’s major sources: Thompson, Mark, Mistrust between states, Oxford University Press, London 1996. No record at WorldCat. No mention at the [Oxford University Press] site. No used listings at Alibris or ABE. I can find no evidence anywhere that this book exists.

He or she added: “Ridiculous.”

Six other editors agreed. And with that, the five-and-a-half-year lie was finally snuffed out of existence.9

A half-decade sounds like a long time. But while impressive, seven other Wikipedia hoaxes have actually lived longer. These include an article on a supposed torture device called “Crocodile Shears” (which persisted for six years and four months) and one on Chen Fang, a Harvard University student who, intent to demonstrate the limitations of Wikipedia, named himself the mayor of a small Chinese town. It took more than seven years for Wikipedia editors to finally strip Chen of that mayorship.10

And then there’s the case of Gaius Flavius Antoninus, whose Wikipedia page described him as a perpetrator in one of the most famous events in history—the assassination of Julius Caesar. “He was later murdered by a male prostitute hired by Mark Antony,” the Wikipedia entry told us. Antoninus, like the Bicholim Conflict, never existed. The hoax evaded Wikipedia ’s legions of volunteers for more than eight years, until it was finally uncovered in July, 2012, and similarly purged from existence.11

Except, not really. While Wikipedia editors do their best to battle the army of trolls and vandals who disrupt the millions of articles on the site, the scams continue to live on elsewhere. There is a small club of Wikipedia copycat sites on the Internet, which scrape, copy, and paste the encyclopedia’s content en masse to their own sites, then plaster it with ads (copying Wikipedia content is legal under its Creative Commons license).12

So while the Bicholim Conflict is now dead on Wikipedia, it still persists on the “New World Encyclopedia” and “Encyclo.”13

And for just $20, you can buy a hard copy.14

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

- What is the Bicholim Conflict? Why, according to Morris, does the problem regarding this conflict continue to exist?

- What does Morris mean when he says, “‘Featured Article’ status is a bit of a badge of honor on Wikipedia” (para. 5)? What is the difference between a “Featured Article” and a “Good Article”?

- What is Morris’s thesis? Restate it in your own words.

- Morris points out that in addition to the Bicholim Conflict, which took five and a half years to remove, “seven other Wikipedia hoaxes have actually lasted longer” (10). Are these eight examples enough to support Morris’s thesis? Explain.

- All the hoaxes that Morris discusses were eventually discovered. Does this fact undermine his thesis? Why or why not?

- Do you think this essay is an argument? Explain.

This article appeared online on December 1, 2014, on Skeptoid.com, a site for critically analyzing popular culture.

ALISON HUDSON

STOP WIKIPEDIA SHAMING

Wikipedia has gotten a bogeyman reputation for inaccuracy. “I read it on Wikipedia” has become a punchline for obviously incorrect information, and any reference to Wikipedia in an article has a tendency to draw derisive comments that essentially dismiss the entire article due to the addition of a link. I’ve come to think of it as “Wikipedia shaming”—deriding and discrediting an article because it happens to reference or link to Wikipedia at some point, regardless of the quality of the information presented both in the Wikipedia link and in the original article. Such views are themselves inaccurate and ill-informed. Wikipedia ’s reputation for unreliability is itself an unreliable position to take.1

I am a college English instructor, and I’ve found it to be a common trope in education that Wikipedia is a useless resource. Every college I have ever worked for had some sort of general academic policy on Wikipedia, mostly “do not let your students reference Wikipedia in their papers.” You can also find examples of such policies online. The reason usually given is that “Wikipedia is non-scholarly and unreliable.”2

They’re half right; Wikipedia is non-scholarly, for sure. But then again, so are a lot of resources people trust. “Non-scholarly” is not a synonym for “not reliable.” “Non-scholarly” simply means “wasn’t written by a credited expert in the field and published in a peer-reviewed journal with complete references.” Despite the fact that many field experts do spend time reading and editing in Wikipedia and Wikipedia articles do strive for complete references, it’s not a scholarly source.3

Where I dissent from the popular view of Wikipedia is in its reputation for unreliability. A 2005 study by Nature found that Wikipedia ’s accuracy was comparable to the Encyclopaedia Britannica (though the writing style was considered inferior). A University of Oxford/Epic e-learning follow-up study released in 2012 (yes, with some support from the Wikimedia Foundation) found that Wikipedia held its own against a variety of reference works. A 2014 study of drug information on Wikipedia found that its drug-related information was 99.7% accurate compared to pharmacological textbooks. If you want a more comprehensive listing of reliability studies on Wikipedia, there’s one place you can go: Wikipedia, which doesn’t shy away from reporting on the good and bad of its own content.4

“But what about that story I heard about the kid who wrote a fake entry and it stayed up for, like, four years?” Yes, that is one of the weaknesses on the model, and one of the reasons I just called it “non-scholarly.” You know who keeps a running list of acknowledged Wikipedia hoaxes? Wikipedia does. And you’ll notice that most of the longstanding ones were able to survive mostly because they were small, unimportant topics that people weren’t likely to be referencing anyway—a made-up but otherwise historically unimportant supposed assassin of Julius Caesar, or someone claiming they were the mayor of a small Chinese town. Vandalism happens, but it’s usually caught fairly quickly and reverted; and the vandals are usually blocked and banned.5

Time is also a factor in Wikipedia ’s reliability. Wikipedia has gotten consistently better since its inception more than a decade ago. Unlike a journal article, a blog post, or the Encyclopaedia Britannica, Wikipedia is constantly being updated. That’s the very nature of the wiki model—allowing the collected knowledge of the world to accrete in one place. Wikipedia also has the Wikimedia Foundation behind it actively looking for ways to improve the information on the site, as well as an entire process of editorial control. The days of “you can write anything you want on Wikipedia” are long gone.6

“The days of ‘you can write anything you want on Wikipedia ’ are long gone.”

It is for all these reasons that I do reference Wikipedia in my blog posts and I will continue to do so in the future. When I do, it’s usually for the purpose of general information, which is exactly what Wikipedia is good for. If someone doesn’t know what ascorbic acid is, it’s much more practical, from a get-the-basics-and-get-back-to-reading perspective, to just link the reader to Wikipedia where they can read the first paragraph or two, get the idea, and then return to the original article.7

Wikipedia is also a good source of links to other resources. One thing I often point out to students in my college courses is that “Wikipedia has more, better citations than your last essay did.” For example, consider the following passage from Wikipedia ’s entry on aspartame:8

The safety of aspartame has been studied extensively since its discovery with research that includes animal studies, clinical and epidemiological research, and postmarketing surveillance,[38] with aspartame being one of the most rigorously tested food ingredients to date.[39] Peer-reviewed comprehensive review articles and independent reviews by governmental regulatory bodies have analyzed the published research on the safety of aspartame and have found aspartame is safe for consumption at current levels.[8][38][40][41] Aspartame has been deemed safe for human consumption by over 100 regulatory agencies in their respective countries,[41] including the UK Food Standards Agency,[42] the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)[43], and Health Canada.[44]

That passage has ten references to eight different sources, many of them the official statements of various government agencies; it also comes from an entry with eighty-five different referenced works. I wish the typical student essay or Internet comment post were so thoroughly sourced!

It’s because of these two views that I often actually tell my students to start with Wikipedia when they conduct research. Many times students, like your typical Internet commenter, know a little bit about a topic but not nearly enough to go on at length. In fact, in some classes I will actually assign the Wikipedia article as a reading assignment and then have them answer some pointed questions based on the information found there. They’re going to read it anyways; I might as well acknowledge the fact and make sure everyone’s got the basics down before they begin the real research. [It also reminds them that I read Wikipedia, too, which usually dissuades at least a few attempts at lazy Wikipedia plagiarism.]9

Of course, I also tell my students to verify information in a second source, because I’m aware that any single source of information may be flawed. That’s not my stance just on Wikipedia, but on any important fact. Starting with Wikipedia is fine; but ending with Wikipedia is a lazy way to do research.10

By the sheer power of its size, Wikipedia actually does what the wiki concept intends to do: it harnesses the collective knowledge of the Internet and distills it into digestible form. Sure, there are weaknesses in the model, but there’s weaknesses in every model. There is no shame in making a general reference to Wikipedia, and there is certainly no shame in mining Wikipedia ’s references for other sources. So please, stop Wikipedia shaming authors who toss an informational link to Wikipedia into their posts. It makes you look petulant and clearly indicates that you didn’t even bother to read the referenced passage and/or you want to avoid the point being made.11

And before you respond to this article with “But look! Here’s an error I found in Wikipedia!” consider this: you found an error on Wikipedia? Good! You’re supposed to. If you’re smart enough to notice it, though, you’re smart enough to correct it, so why not make your own little contribution to the collected knowledge of the Internet community. Just be ready to credit a source; unlike most discussion forums or comments sections, Wikipedia demands citation.12

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

- Hudson begins her essay discussing the major arguments against Wikipedia. Why does she begin this way? Is this an effective strategy?

- What is “Wikipedia shaming”?

- Explain the difference between the terms non-scholarly and not reliable. Why does Hudson disagree with the generally held view that Wikipedia is not a reliable source? What evidence does she present to support this position?

- According to Hudson, what are the strengths of Wikipedia?

- At what point does Hudson address opposing arguments? How effectively does she refute them?

- In paragraph 7, Hudson notes that she refers to Wikipedia in her blog posts. Why does she mention this? Do you agree with her rationale for doing so? Why or why not?

Wikipediocracy.com, a site dedicated to exploring issues related to Wikipedia, posted this article on February 16, 2014.

ANDREAS KOLBE

DEBUNKING THE “ACCURATE AS BRITANNICA” MYTH

A factoid regularly cited in the press to this day is that a 2005 study by Nature found Wikipedia to be almost as reliable as Britannica. While the study’s (if that is the right word—it wasn’t a peer-reviewed study, but a news story) methodology and conclusions were disputed by Britannica, the result of the Nature comparison has become part of received knowledge for much of the media. As the saying goes, a lie told often enough becomes the truth.1

“As the saying goes, a lie told often enough becomes the truth.”

A Meme Is Born

The problems really began as soon as the Nature piece was published. Many news outlets failed to mention that in its survey, Nature looked at hard science topics only—subjects like physics, chemistry, biology, astronomy and paleontology—despite the fact that Nature clearly said so, in the very first line of its piece. The following headline and lead from CNET will serve as an example:

Study: Wikipedia as accurate as Britannica.

Wikipedia is about as good a source of accurate information as Britannica, the venerable standard-bearer of facts about the world around us, according to a study published this week in the journal Nature.

Few observers were astute enough to note, as the Register ’s Andrew Orlowski did, that restricting the comparison to hard science articles was what “gave the free-for-all web site a fighting chance—as it excluded the rambling garbage and self-indulgence that constitute much of the wannabe encyclopedia’s social science and culture entries.” Another notable exception was Bill Thompson, writing for the BBC, who noted Wikipedia ’s problems in “contentious areas such as politics, religion or biography,” and how easily Wikipedia can “be undermined through malice or ignorance thanks to its open architecture.”2

Nicholas Carr put it this way: in limiting itself to topics like the “kinetic isotope effect” or “Meliaceae,” which no one without some specialized understanding of the subject matter would even be aware of, the Nature survey played to Wikipedia ’s strengths. Carr also established that the Nature “study” was not actually an expert-written research article of the type that built the reputation of Nature, but a non-peer-reviewed piece of news journalism (a fact he confirmed with the piece’s author, Jim Giles).3

Another fact that is largely forgotten today: the Nature survey found that many Wikipedia entries were “poorly structured and confusing” and gave undue prominence to controversial theories. Both of these failings are a result of Wikipedia ’s crowdsourcing method—one editor adding a sentence here, another adding a sentence there. The study’s highly publicized count of “in-accuracies,” which led to the “Wikipedia is as accurate as Britannica” meme, did not reflect that. While the count penalized Britannica for alleged omissions—which Britannica contested—it imposed no penalty on Wikipedia for meandering off topic.4

In effect, it considered a sprawling, badly organized jumble of facts to be as valuable as a masterfully written and easy-to-understand introduction to a topic by a world-renowned scholar. The results are not the same. Even so, Nature found that Wikipedia contained about a third more inaccuracies than Britannica. (This doesn’t stop some writers going the whole hog and claiming that Nature found Wikipedia to be more reliable than Britannica. It’s stunning, really, how memes morph on the internet.)5

The Reality: A Site Riddled with Hoaxes, Vandalism, PR Manipulation, and Anonymous Defamation

Another point that was lost is that Wikipedia ’s quality is very uneven. Wikipedia articles on more obscure topics are often lacking in basic literacy. In the worst case, the information they contain may be entirely made up, or so self-serving to the interests of some anonymous Wikipedia author as to make a mockery of Wikipedia ’s vaunted concept of a “neutral point of view.”6

Saying that Wikipedia is “as reliable as Britannica” implies that this is so for any article in Wikipedia. And that just ain’t so. Some of Wikipedia ’s articles are indeed reliable. The problem is that you never know whether the article you are looking at is one of them.7

Wikipedia contains hoaxes and vandalism. It contains malicious defamation and anonymous hatchet jobs authored by people who are in conflict with the person they are writing about, or simply jealous of their success. It contains barely disguised advertising—entries on people and companies written by their subjects, or their PR agents. It contains articles on politics and history that have been meddled with by political extremists. Wikipedia entries are protean edifices: they may say one thing today and a completely different thing tomorrow. Those are all problems conventional reference works like Britannica never had. Is this progress?8

“Wikipedia contains hoaxes and vandalism.”

What reference works like Britannica do have are editors in the traditional sense of the word—experts in their fields, who ensure that what is published meets academic standards. Wikipedia has editors, too, but in Jimmy Wales’ online encyclopedia the word means something entirely different: it is applied to any anonymous person with an internet connection who clicks “Edit” on a Wikipedia page—whether it’s a schoolchild, a mentally disturbed person, a political activist, a knowledgeable amateur, or an actual scholar. Wikipedia has all of them. But academics venturing into the “encyclopedia anyone can edit” (allegedly) often find it a very time-consuming and frustrating experience, punctuated by interminable arguments with young men who may only have a very superficial understanding of the academic’s area of expertise, but unlimited time to spend on Wikipedia, familiarity with the site’s arcane and self-contradictory policies and guidelines, and wiki-friends to back them up. Many a distinguished academic lacks the time and patience to engage with them, and has been blocked from further participation for “incivility.” It’s not the same as talking to your editor at a university press!9

Horses for Courses

Wikipedia is free. It’s understandable that people don’t like to look a gift horse in the mouth. But no one should fool themselves into thinking that the nag they got for free is an Arabian racehorse.10

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING ADEFINITION ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING ADEFINITION ARGUMENT

- What does Kolbe mean in paragraph 1 when he says, “[A] lie told often enough becomes the truth”? What lie does Kolbe address in his essay?

- What point does Kolbe concede in paragraph 7? How does he go on to refute this point?

- According to Kolbe, what is the major strength of Britannica?

- Kolbe clearly does not consider Wikipedia a source of reliable information. Why not? Do any of his arguments seem unfair or biased? Explain.

- What point does Kolbe make in his conclusion? Why does he focus on the fact that Wikipedia is free?

The New York Times published this essay on March 12, 2006.

RANDALL STROSS

ANONYMOUS SOURCE IS NOT THE SAME AS OPEN SOURCE

Concerning the nature of knowledge

Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia, currently serves up the following: Five billion pages a month. More than 120 languages. In excess of one million English-language articles. And a single nagging epistemological° question: Can an article be judged as credible without knowing its author?1

Wikipedia says yes, but I am unconvinced.2

Qualifications such as a degree in a field

Dispensing with experts, the Wikipedians invite anyone to pitch in, writing an article or editing someone else’s. No expertise is required, nor even a name. Sound inviting? You can start immediately. The system rests upon the belief that a collectivity of unknown but enthusiastic individuals, by dint of sheer mass rather than possession of conventional credentials,° can serve in the supervisory role of editor. Anyone with an interest in a topic can root out inaccuracies and add new material.3

At first glance, this sounds straightforward. But disagreements arise all the time about what is a problematic passage or an encyclopedia-worthy topic, or even whether a putative correction improves or detracts from the original version.4

The egalitarian nature of a system that accords equal votes to everyone in the “community”—middle-school student and Nobel laureate alike—has difficulty resolving intellectual disagreements.5

Wikipedia ’s reputation and internal editorial process would benefit by having a single authority vouch for the quality of a given article. In the jargon of library and information science, lay readers rely upon “secondary epistemic criteria,” clues to the credibility of information when they do not have the expertise to judge the content.6

Once upon a time, Encyclopaedia Britannica recruited Einstein, Freud, Curie, Mencken, and even Houdini as contributors. The names helped the encyclopedia bolster its credibility. Wikipedia, by contrast, provides almost no clues for the typical article by which reliability can be appraised. A list of edits provides only screen names or, in the case of the anonymous editors, numerical Internet Protocol addresses. Wasn’t yesterday’s practice of attaching “Albert Einstein” to an article on “Space-Time” a bit more helpful than today’s “71.240.205.101”?7

“What does Wikipedia’ s system offer in place of an expert authority?”

What does Wikipedia ’s system offer in place of an expert authority willing to place his or her professional reputation on the line with a signature attached to an article?8

When I asked Jimmy Wales, the founder of Wikipedia, last week, he discounted the importance of individual contributors to Britannica. “When people trust an article in Britannica,” he said, “it’s not who wrote it, it’s the process.” There, a few editors review a piece and then editing ceases. By contrast, Wikipedia is built with unending scrutiny and ceaseless editing.9

He predicts that in the future, it will be Britannica ’s process that will seem strange: “People will say, ‘This was written by one person? Then looked at by only two or three other people? How can I trust that process?’”10

The Wikipedian hive is capable of impressive feats. The English-language collection recently added its millionth article, for example. It was about the Jordanhill railway station, in Glasgow. The original version, a few paragraphs, appeared to say all that a lay reader would ever wish to know about it. But the hive descended and in a week, more than 640 edits were logged.11

If every topic could be addressed like this, without recourse to specialized learning—and without the heated disputes called flame wars—the anonymous hive could be trusted to produce work of high quality. But the Jordanhill station is an exception.12

Biographical entries, for example, are often accompanied by controversy. Several recent events have shown how anyone can tamper with someone else’s entry. Congressional staff members have been unmasked burnishing articles about their employers and vandalizing those of political rivals. (Sample addition: “He likes to beat his wife and children.”)13

Mr. Wales himself ignored the encyclopedia’s guidelines about “Dealing with Articles about Yourself” and altered his own Wikipedia biography; when other editors undid them, he reapplied his changes. The incidents, even if few in number, do not help Wikipedia establish the legitimacy of a process that is reluctant to say no to anyone.14

It should be noted that Mr. Wales is a full-time volunteer, and that neither he nor the thousands of fellow volunteer editors has a pecuniary interest in this nonprofit project. He also deserves accolades for keeping Wikipedia operating without the intrusion of advertising, at least so far.15

Most winningly, he has overseen a system that is gleefully candid in its public self-examination. If you’re seeking a well-organized list of criticisms of Wikipedia, you won’t find a better place than Wikipedia ’s coverage of itself. Wikipedia also provides a taxonomy of no fewer than 23 different forms of vandalism that strike it.16

It is easy to forget how quickly Wikipedia has grown; it began only in 2001. With the passage of a little more time, Mr. Wales and his associates may come around to the idea that identifying one person as a given article’s supervising editor would enhance the encyclopedia’s reputation.17

Mr. Wales has already responded to recent negative articles about vandalism at the site with announcements of modest reforms. Anonymous visitors are no longer permitted to create pages, though they still may edit existing ones.18

To curb what Mr. Wales calls “drive-by pranks” that are concentrated on particular articles, he has instituted a policy of “semi-protection.” In these cases, a user must have registered at least four days before being permitted to make changes to the protected article. “If someone really wants to write ‘George Bush is a poopy head,’ you’ve got to wait four days,” he said.19

When asked what problems on the site he viewed as most pressing, Mr. Wales said he was concerned with passing along the Wikipedian culture to newcomers. He sounded wistful when he spoke of the days not so long ago when he could visit an article that was the subject of a flame war and would know at least some participants—and whether they could resolve the dispute tactfully.20

As the project has grown, he has found that he no longer necessarily knows anyone in a group. When a dispute flared recently over an article related to a new dog breed, he looked at the discussion and asked himself in frustration, “Who are these people?”21

Isn’t this precisely the question all users are bound to ask about contributors?22

By wide agreement, the print encyclopedia in the English world reached its apogee in 1911, with the completion of Encyclopaedia Britannica ’s 11th edition. (For the fullest tribute, turn to Wikipedia.) But the Wikipedia experiment need not be pushed back in time toward that model. It need only be pushed forward, so it can catch up to others with more experience in online collaboration: the open-source software movement.23

Wikipedia and open-source projects like Linux are similarly noncommercial, intellectual enterprises, mobilizing volunteers who will probably never meet one another in person. But even though Wikipedians like to position their project under the open-source umbrella, the differences are wide.24

Jeff Bates, a vice president of the Open Source Technology Group who oversees SourceForge.net, the host of more than 80,000 active open-source projects, said, “It makes me grind my teeth to hear Wikipedia compared to open source.” In every open-source project, he said, there is “a benevolent dictator” who ultimately takes responsibility, even though the code is contributed by many. Good stuff results only if “someone puts their name on it.”25

Wikipedia has good stuff, too. These have been designated “featured articles.” But it will be a long while before all one-million-and-counting entries have been carefully double-checked and buffed to a high shine. Only 923 have been granted “featured” status, and the consensus-building process is presently capable of adding only about one a day.26

Mr. Wales is not happy with this pace and seems open to looking again at the open-source software model for ideas. Software development that relies on scattered volunteers is a two-step process: first, a liberal policy encourages the contributions of many, then a restrictive policy follows to stabilize the code in preparation for release. Wikipedia, he said, has “half the model.”27

There’s no question that Wikipedia volunteers can address many more topics than the lumbering, for-profit incumbents like Britannica and World Book, and can update entries swiftly. Still, anonymity blocks credibility. One thing that Wikipedians have exactly right is that the current form of the encyclopedia is a beta test. The quality level that would permit speaking of Version 1.0 is still in the future.28

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR DEVELOPING A DEFINITION ARGUMENT

- In paragraph 3, Stross presents the Wikipedia philosophy. In your own words, summarize this philosophy.

- At what points in his essay does Stross refute the Wikipedia philosophy? What aspects of this philosophy does he seem to disagree with most?

- Do you think Stross should have provided formal definitions of the terms anonymous source and open source? Why or why not?

- Where in the essay does Stross acknowledge Wikipedia ’s strengths? Do you think that the encyclopedia’s strengths outweigh its weaknesses? Explain.

- Do you agree with Jimmy Wales, founder of Wikipedia, that in the future, Britannica’ s process “will seem strange” (para. 10)? Why or why not?

- What does Stross mean when he says, “Version 1.0 is still in the future” (28)?

This Web page was accessed on January 30, 2012.

WIKIPEDIA

WIKIPEDIA: ABOUT

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia1

A general introduction for visitors to Wikipedia. The project also has an encyclopedia article about itself, Wikipedia, and some introductions for aspiring contributors.2

For Wikipedia ’s formal organizational structure, see Wikipedia: Formal organization.3

Wikipedia (![]() or 4

or 4 ![]() ) is a multilingual, web-based, free-content encyclopedia project based on an openly editable model. The name Wikipedia is a portmanteau of the words wiki (a technology for creating collaborative websites, from the Hawaiian word wiki, meaning “quick”) and encyclopedia. Wikipedia ’s articles provide links to guide the user to related pages with additional information.4

) is a multilingual, web-based, free-content encyclopedia project based on an openly editable model. The name Wikipedia is a portmanteau of the words wiki (a technology for creating collaborative websites, from the Hawaiian word wiki, meaning “quick”) and encyclopedia. Wikipedia ’s articles provide links to guide the user to related pages with additional information.4

English Wikipedia right now

Wikipedia is running MediaWiki version 1.18wmf1 (r109351).

It has 3,859,117 content articles, and 26,106,710 pages in total.

There have been 513,565,315 edits.

There are 797,211 uploaded files.

There are 16,163,858 registered users, including 1,507 administrators.

This information is correct as of 18:50, 30 January 2012 (UTC).

Wikipedia is written collaboratively by largely anonymous Internet volunteers who write without pay. Anyone with Internet access can write and make changes to Wikipedia articles (except in certain cases where editing is restricted to prevent disruption or vandalism). Users can contribute anonymously, under a pseudonym, or with their real identity, if they choose.5

The fundamental principles by which Wikipedia operates are the five pillars. The Wikipedia community has developed many policies and guidelines to improve the encyclopedia; however, it is not a formal requirement to be familiar with them before contributing.6

Since its creation in 2001, Wikipedia has grown rapidly into one of the largest reference websites, attracting 400 million unique visitors monthly as of March 2011 according to ComScore. There are more than 82,000 active contributors (http://en.wikipedia.org/wikistats/EN/TablesWikipediansEditsGt5.htm) working on more than 19,000,000 articles in more than 270 languages. As of today, there are 3,859,117 articles in English. Every day, hundreds of thousands of visitors from around the world collectively make tens of thousands of edits and create thousands of new articles to augment the knowledge held by the Wikipedia encyclopedia. (See also Wikipedia: Statistics.)7

People of all ages, cultures, and backgrounds can add or edit article prose, references, images, and other media here. What is contributed is more important than the expertise or qualifications of the contributor. What will remain depends upon whether it fits within Wikipedia ’s policies, including being verifiable against a published reliable source, so excluding editors’ opinions and beliefs and unreviewed research, and is free of copyright restrictions and contentious material about living people. Contributions cannot damage Wikipedia because the software allows easy reversal of mistakes and many experienced editors are watching to help ensure that edits are cumulative improvements. Begin by simply clicking the edit link at the top of any editable page!8