Revising to Eliminate Plagiarism

As you revise your papers, scrutinize your work carefully to be sure you have not inadvertently committed plagiarism.

The following paragraph (from page 28 of Hot, Flat, and Crowded by Thomas L. Friedman) and the four guidelines that follow it will help you to understand the situations in which accidental plagiarism is most likely to occur.

So if you think the world feels crowded now, just wait a few decades. In 1800, London was the world’s largest city with one million people. By 1960, there were 111 cities with more than one million people. By 1995 there were 280, and today there are over 300, according to UN Population Fund statistics. The number of megacities (with ten million or more inhabitants) in the world has climbed from 5 in 1975 to 14 in 1995 and is expected to reach 26 cities by 2015, according to the UN. Needless to say, these exploding populations are rapidly overwhelming infrastructure in these megacities—nineteen million people in Mumbai alone—as well as driving loss of arable land, deforestation, overfishing, water shortages, and air and water pollution.

Be sure you have identified your source and provided appropriate documentation.

PLAGIARISM

The world is becoming more and more crowded, and some twenty-six cities are expected to have populations of over 10 million by 2015.

This student writer does not quote directly from Friedman’s discussion, but her summary of his comments does not represent her original ideas and therefore needs to be documented.

The following correct use of source material includes both an identifying tag (a phrase that identifies Friedman as the source of the ideas) and a page number that directs readers to the exact location of the material the student is summarizing. (Full source information is provided in the works-cited list.)

CORRECT

According to Thomas L. Friedman, the world is becoming more and more crowded, and twenty-six cities are expected to have populations of over 10 million by 2015 (28).

Be sure you have placed quotation marks around borrowed words.

PLAGIARISM

According to Thomas L. Friedman, the exploding populations of mega-cities around the world are overwhelming their infrastructure (28).

Although the passage above provides parenthetical documentation and includes an identifying tag indicating the source of its ideas, it uses Friedman’s exact words without placing them in quotation marks.

To avoid committing plagiarism, the writer needs to either place quotation marks around Friedman’s words or paraphrase his comments.

Correct (BORROWED WORDS IN QUOTATION MARKS)

According to Thomas L. Friedman, the “exploding populations” of large cities around the world are “rapidly overwhelming infrastructure in these megacities” (28).

Correct (BORROWED WORDS PARAPHRASED)

According to Thomas L. Friedman, the rapid rise in population of large cities around the world poses a serious threat to their ability to function (28).

Be sure you have indicated the boundaries of the borrowed material.

PLAGIARISM

The world is becoming more and more crowded, and this will lead to serious problems in the future. Soon, as many as twenty-six of the world’s cities will have populations over 10 million. It is clear that “these exploding populations are rapidly overwhelming infrastructure in these megacities” (Friedman 28).

In the passage above, the student correctly places Friedman’s words in quotation marks and includes appropriate parenthetical documentation. However, she does not indicate that other ideas in the passage, although not quoted directly, are also Friedman’s.

To avoid committing plagiarism, the student needs to use identi fying tags to indicate the boundaries of the borrowed material, which goes beyond the quoted words.

CORRECT

According to Thomas L. Friedman, the world is becoming more and more crowded, and this will lead to serious problems in the future. Soon, Friedman predicts, as many as twenty-six of the world’s cities will have populations of over 10 million, and this rise in population will put a serious strain on the cities’ resources, “rapidly overwhelming infrastructure in these megacities” (28).

Be sure you have used your own phrasing and syntax.

PLAGIARISM

If you feel crowded now, Thomas L. Friedman says, just wait twenty or thirty years. In 1800, London, with a million inhabitants, was the largest city in the world; over 111 cities had more than a million people by 1960. Thirty-five years later, there were 280; today, according to statistics provided by the UN Population Fund, there are more than 300. There were only five megacities (10 million people or more) in 1975 and fourteen in 1995. However, by 2015, the United Nations predicts, there might be twenty-six. These rapidly growing populations threaten to overwhelm the infrastructure of the mega cities (Mumbai alone has 19 million people), destroying arable land, the forests, and fishing and causing water shortages and water and air pollution (28).

The student who wrote the paragraph on the preceding page does provide an identifying tag and parenthetical documentation to identify the source of her ideas. However, her paragraph’s phrasing and syntax are almost identical to Friedman’s.

In the following paragraph, the writer correctly paraphrases and summarizes Friedman’s ideas, quoting a few distinctive passages. (See Chapter 9 for information on paraphrase and summary.)

CORRECT

As Thomas L. Friedman warns, the world has been growing more and more crowded and is likely to grow still more crowded in the years to come. Relying on UN population data, Friedman estimates that there will be some twenty more “megacities” (those with more than 10 million people) in 2015 than there were in 1975. (In 1800, in contrast, only one city in the world—London—had a million inhabitants.) Obviously, this is an alarming trend. Friedman believes that these rapidly growing populations are “overwhelming infrastructure in these megacities” and are bound to strain resources, leading to “loss of arable land, deforestation, [and] overfishing” and creating not only air and water pollution but water shortages as well (28).

STUDENT PARAGRAPH

In recent years, psychologists have focused on the idea that girls (unlike boys) face a crisis of self-esteem as they approach adolescence. Both Carol Gilligan and Mary Pipher did research to support this idea, showing how girls lose their self-confidence in adolescence because of sexist cultural expectations. Women’s groups have expressed concern that the school system favors boys and is biased against girls. In fact, boys are often regarded not just as classroom favorites but also as bullies who represent obstacles on the path to gender justice for girls. Recently, however, this impression that boys are somehow privileged while girls are shortchanged is being challenged.

Source 1

That boys are in disrepute is not accidental. For many years women’s groups have complained that boys benefit from a school system that favors them and is biased against girls. “Schools shortchange girls,” declares the American Association of University Women…. A stream of books and pamphlets cite research showing not only that boys are classroom favorites but also that they are given to schoolyard violence and sexual harassment.

In the view that has prevailed in American education over the past decade, boys are resented, both as the unfairly privileged sex and as obstacles on the path to gender justice for girls. This perspective is promoted in schools of education, and many a teacher now feels that girls need and deserve special indemnifying consideration. “It is really clear that boys are Number One in this society and in most of the world,” says Patricia O’Reilly, a professor of education and the director of the Gender Equity Center, at the University of Cincinnati.

The idea that schools and society grind girls down has given rise to an array of laws and policies intended to curtail the advantage boys have and to redress the harm done to girls. That girls are treated as the second sex in school and consequently suffer, that boys are accorded privileges and consequently benefit—these are things everyone is presumed to know. But they are not true.

—CHRISTINA HOFF SOMMERS, “THE WAR AGAINST BOYS”

Source 2

Girls face an inevitable crisis of self-esteem as they approach adolescence. They are in danger of losing their voices, drowning, and facing a devastating dip in self-regard that boys don’t experience. This is the picture that Carol Gilligan presented on the basis of her research at the Emma Willard School, a private girls’ school in Troy, N.Y. While Gilligan did not refer to genes in her analysis of girls’ vulnerability, she did cite both the “wall of Western culture” and deep early childhood socialization as reasons.

Her theme was echoed in 1994 by the clinical psychologist Mary Pipher’s surprise best seller, Reviving Ophelia (Putnam, 1994), which spent three years on the New York Times best-seller list. Drawing on case studies rather than systematic research, Pipher observed how naturally outgoing, confident girls get worn down by sexist cultural expectations. Gilligan’s and Pipher’s ideas have also been supported by a widely cited study in 1990 by the American Association of University Women. That report, published in 1991, claimed that teenage girls experience a “free-fall in self-esteem from which some will never recover.”

The idea that girls have low self-esteem has by now become part of the academic canon as well as fodder for the popular media. But is it true? No.

—ROSALIND C. BARNETT AND CARYL RIVERS, “MEN ARE FROM EARTH, AND SO ARE WOMEN. It’s Faulty Research That Sets Them Apart”

In this Slate article, Shafer accuses a New York Times reporter of plagiarism. As evidence, he presents the opening paragraphs from the source (a Bloomberg News story), the accused reporter’s New York Times article, and—for contrast—two other newspaper articles that report the same story without relying heavily on the original source.

This essay appeared in the Washington Post on September 3, 2004.

LAWRENCE M. HINMAN

HOW TO FIGHT COLLEGE CHEATING

Recent studies have shown that a steadily growing number of students cheat or plagiarize in college—and the data from high schools suggest that this number will continue to rise. A study by Don McCabe of Rutgers University showed that 74 percent of high school students admitted to one or more instances of serious cheating on tests. Even more disturbing is the way that many students define cheating and plagiarism. For example, they believe that cutting and pasting a few sentences from various Web sources without attribution is not plagiarism.1

Before the Web, students certainly plagiarized—but they had to plan ahead to do so. Fraternities and sororities often had files of term papers, and some high-tech term-paper firms could fax papers to students. Overall, however, plagiarism required forethought.2

Online term-paper sites changed all that. Overnight, students could order a term paper, print it out, and have it ready for class in the morning—and still get a good night’s sleep. All they needed was a charge card and an Internet connection.3

One response to the increase in cheating has been to fight technology with more technology. Plagiarism-checking sites provide a service to screen student papers. They offer a color-coded report on papers and the original sources from which the students might have copied. Colleges qualify for volume discounts, which encourages professors to submit whole classes’ worth of papers—the academic equivalent of mandatory urine testing for athletes.4

The technological battle between term-paper mills and anti-plagiarism services will undoubtedly continue to escalate, with each side constructing more elaborate countermeasures to outwit the other. The cost of both plagiarism and its detection will also undoubtedly continue to spiral.5

“The cost of both plagiarism and its detection will also undoubtedly continue to spiral.”

But there is another way. Our first and most important line of defense against academic dishonesty is simply good teaching. Cheating and plagiarism often arise in a vacuum created by routine, lack of interest, and overwork. Professors who give the same assignment every semester, fail to guide students in the development of their projects, and have little interest in what the students have to say contribute to the academic environment in which much cheating and plagiarism occurs.6

Consider, by way of contrast, professors who know their students and who give assignments that require regular, continuing interaction with them about their projects—and who require students to produce work that is a meaningful development of their own interests. These professors create an environment in which cheating and plagiarism are far less likely to occur. In this context, any plagiarism would usually be immediately evident to the professor, who would see it as inconsistent with the rest of the student’s work. A strong, meaningful curriculum taught by committed professors is the first and most important defense against academic dishonesty.7

The second remedy is to encourage the development of integrity in our students. A sense of responsibility about one’s intellectual development would preclude cheating and plagiarizing as inconsistent with one’s identity. It is precisely this sense of individual integrity that schools with honor codes seek to promote.8

Third, we must encourage our students to perceive the dishonesty of their classmates as something that causes harm to the many students who play by the rules. The argument that cheaters hurt only themselves is false. Cheaters do hurt other people, and they do so to help themselves. Students cheat because it works. They get better grades and more advantages with less effort. Honest students lose grades, scholarships, recommendations, and admission to advanced programs. Honest students must create enough peer pressure to dissuade potential cheaters. Ultimately, students must be willing to step forward and confront those who engage in academic dishonesty.9

Addressing these issues is not a luxury that can be postponed until a more convenient time. It is a short step from dishonesty in schools and colleges to dishonesty in business. It is doubtful that students who fail to develop habits of integrity and honesty while still in an academic setting are likely to do so once they are out in the “real” world. Nor is it likely that adults will stand up against the dishonesty of others, particularly fellow workers and superiors, if they do not develop the habit of doing so while still in school.10

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

In the first five paragraphs of this essay, Hinman provides background on how plagiarism by students has been changed by the Internet. Summarize the plagiarism situation before and after the development of the Internet.

The essay’s thesis is stated in paragraph 6. Restate this thesis in your own words.

Does Hinman view plagiarism-detection sites as a solution to the problem of college cheating? What are the limitations of such sites?

According to Hinman, what steps can “committed professors” (para. 7) take to eliminate academic dishonesty?

In paragraphs 8 and 9, Hinman suggests two additional solutions to the problem of plagiarism. What solutions does he propose? Given what you know about college students, do you think Hinman’s suggestions are realistic? Explain.

Hinman does not address arguments that challenge his recommendations. What opposing arguments might he have presented? How would you refute these opposing arguments?

This essay was published more than ten years ago. Do you think Hinman’s observations and recommendations are still valid? Why or why not?

This article is from the August 1, 2010, edition of the New York Times.

TRIP GABRIEL

PLAGIARISM LINES BLUR FOR STUDENTS IN DIGITAL AGE

At Rhode Island College, a freshman copied and pasted from a Web site’s frequently asked questions page about homelessness—and did not think he needed to credit a source in his assignment because the page did not include author information.1

At DePaul University, the tip-off to one student’s copying was the purple shade of several paragraphs he had lifted from the Web; when confronted by a writing tutor his professor had sent him to, he was not defensive—he just wanted to know how to change purple text to black.2

And at the University of Maryland, a student reprimanded for copying from Wikipedia in a paper on the Great Depression said he thought its entries—unsigned and collectively written—did not need to be credited since they counted, essentially, as common knowledge.3

Professors used to deal with plagiarism by admonishing students to give credit to others and to follow the style guide for citations, and pretty much left it at that.4

But these cases—typical ones, according to writing tutors and officials responsible for discipline at the three schools who described the plagiarism—suggest that many students simply do not grasp that using words they did not write is a serious misdeed.5

It is a disconnect that is growing in the Internet age as concepts of intellectual property, copyright, and originality are under assault in the unbridled exchange of online information, say educators who study plagiarism.6

Digital technology makes copying and pasting easy, of course. But that is the least of it. The Internet may also be redefining how students—who came of age with music file-sharing, Wikipedia, and Web-linking—understand the concept of authorship and the singularity of any text or image.7

“Now we have a whole generation of students who’ve grown up with information that just seems to be hanging out there in cyberspace and doesn’t seem to have an author,” said Teresa Fishman, director of the Center for Academic Integrity at Clemson University. “It’s possible to believe this information is just out there for anyone to take.”8

Professors who have studied plagiarism do not try to excuse it—many are champions of academic honesty on their campuses—but rather try to understand why it is so widespread.9

In surveys from 2006 to 2010 by Donald L. McCabe, a co-founder of the Center for Academic Integrity and a business professor at Rutgers University, about 40 percent of 14,000 undergraduates admitted to copying a few sentences in written assignments.10

Perhaps more significant, the number who believed that copying from the Web constitutes “serious cheating” is declining—to 29 percent on average in recent surveys from 34 percent earlier in the decade.11

Sarah Brookover, a senior at the Rutgers campus in Camden, N.J., said many of her classmates blithely cut and paste without attribution.12

“This generation has always existed in a world where media and intellectual property don’t have the same gravity,” said Ms. Brookover, who at 31 is older than most undergraduates. “When you’re sitting at your computer, it’s the same machine you’ve downloaded music with, possibly illegally, the same machine you streamed videos for free that showed on HBO last night.”13

Ms. Brookover, who works at the campus library, has pondered the differences between researching in the stacks and online. “Because you’re not walking into a library, you’re not physically holding the article, which takes you closer to ‘this doesn’t belong to me,’” she said. Online, “everything can belong to you really easily.”14

“Online, ‘everything can belong to you really easily.’”

A University of Notre Dame anthropologist, Susan D. Blum, disturbed by the high rates of reported plagiarism, set out to understand how students view authorship and the written word, or “texts” in Ms. Blum’s academic language.15

She conducted her ethnographic research among 234 Notre Dame undergraduates. “Today’s students stand at the crossroads of a new way of conceiving texts and the people who create them and who quote them,” she wrote last year in the book My Word! Plagiarism and College Culture, published by Cornell University Press.16

Ms. Blum argued that student writing exhibits some of the same qualities of pastiche that drive other creative endeavors today—TV shows that constantly reference other shows or rap music that samples from earlier songs.17

In an interview, she said the idea of an author whose singular effort creates an original work is rooted in Enlightenment ideas of the individual. It is buttressed by the Western concept of intellectual property rights as secured by copyright law. But both traditions are being challenged. “Our notion of authorship and originality was born, it flourished, and it may be waning,” Ms. Blum said.18

She contends that undergraduates are less interested in cultivating a unique and authentic identity—as their 1960s counterparts were—than in trying on many different personas, which the Web enables with social networking.19

“If you are not so worried about presenting yourself as absolutely unique, then it’s O.K. if you say other people’s words, it’s O.K. if you say things you don’t believe, it’s O.K. if you write papers you couldn’t care less about because they accomplish the task, which is turning something in and getting a grade,” Ms. Blum said, voicing student attitudes. “And it’s O.K. if you put words out there without getting any credit.”20

The notion that there might be a new model young person, who freely borrows from the vortex of information to mash up a new creative work, fueled a brief brouhaha earlier this year with Helene Hegemann, a German teenager whose best-selling novel about Berlin club life turned out to include passages lifted from others.21

Instead of offering an abject apology, Ms. Hegemann insisted, “There’s no such thing as originality anyway, just authenticity.” A few critics rose to her defense, and the book remained a finalist for a fiction prize (but did not win).22

That theory does not wash with Sarah Wilensky, a senior at Indiana University, who said that relaxing plagiarism standards “does not foster creativity, it fosters laziness.”23

“You’re not coming up with new ideas if you’re grabbing and mixing and matching,” said Ms. Wilensky, who took aim at Ms. Hegemann in a column in her student newspaper headlined “Generation Plagiarism.”24

“It may be increasingly accepted, but there are still plenty of creative people—authors and artists and scholars—who are doing original work,” Ms. Wilensky said in an interview. “It’s kind of an insult that that ideal is gone, and now we’re left only to make collages of the work of previous generations.”25

In the view of Ms. Wilensky, whose writing skills earned her the role of informal editor of other students’ papers in her freshman dorm, plagiarism has nothing to do with trendy academic theories.26

The main reason it occurs, she said, is because students leave high school unprepared for the intellectual rigors of college writing.27

“If you’re taught how to closely read sources and synthesize them into your own original argument in middle and high school, you’re not going to be tempted to plagiarize in college, and you certainly won’t do so unknowingly,” she said.28

At the University of California, Davis, of the 196 plagiarism cases referred to the disciplinary office last year, a majority did not involve students ignorant of the need to credit the writing of others.29

Many times, said Donald J. Dudley, who oversees the discipline office on the campus of 32,000, it was students who intentionally copied—knowing it was wrong—who were “unwilling to engage the writing process.”30

“Writing is difficult, and doing it well takes time and practice,” he said.31

And then there was a case that had nothing to do with a younger generation’s evolving view of authorship. A student accused of plagiarism came to Mr. Dudley’s office with her parents, and the father admitted that he was the one responsible for the plagiarism. The wife assured Mr. Dudley that it would not happen again.32

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

Gabriel begins inductively, presenting three paragraphs of evidence before he states his thesis. Is this the best strategy, or should these examples appear later in his discussion? Explain.

In paragraph 5, Gabriel notes that “many students simply do not grasp that using words they did not write is a serious misdeed.” Is this his thesis statement? Does he take a position, or is he just presenting information?

Why, according to Gabriel, is plagiarism so widespread? Do you think the reasons he cites in any way excuse plagiarism—at least accidental plagiarism? Does Gabriel seem to think they do?

What is pastiche (para. 17)? What is a collage (25)? How does the concept of pastiche or collage apply to plagiarism? Do you see the use of pastiche in TV shows or popular music (17) as different from its use in academic writing? Why or why not?

Summarize Sarah Wilensky’s views (23–28) on the issue Gabriel discusses. Do you agree with her? Do you agree with Helene Hegemann’s statement, “There’s no such thing as originality anyway, just authenticity” (22)?

Do you think the anecdote in paragraph 32 is a strong ending for this article? Does the paragraph need a more forceful concluding statement? Explain.

This essay appeared on the New Yorker ’s “Book Bench” blog on August 4, 2010.

ELIZABETH MINKEL

TOO HARD NOT TO CHEAT IN THE INTERNET AGE?

A deeply troubling article sat atop the New York Times’ most-emailed list yesterday (no, not the one about catching horrible diseases at the gym). “Plagiarism Lines Blur for Students in Digital Age,” the headline proclaimed, pinpointing a problem, weaving a theory, and excusing youthful copycats in one fell swoop. The story here is that a large number of college students today are acting as college students always have—baldly lifting whole passages for their term papers from other sources. But it’s the Digital Age now, and between unverifiable, unattributed information sitting around online and the general ease with which young people obtain, alter, and share creative content on the Internet, students can’t seem to figure out that cheating on a paper is wrong. In fact, a lot of them can’t even tell that they’re cheating, and the Internet is to blame.1

Really? When I was in college (I graduated three years ago), I was well aware of the necessity of avoiding minefields of unattributed—and often in correct—information on the Web. Wikipedia was never an acceptable source, perhaps because my professors knew they’d get students like the one from the University of Maryland who, when “reprimanded for copying from Wikipedia… said he thought its entries—unsigned and collectively written—did not need to be credited since they counted, essentially, as common knowledge.” There are probably only two types of people pulling these excuses: the crafty, using the Digital Age argument to their advantage, and the completely clueless, who, like plenty in preceding generations, just don’t understand the concept of plagiarism. The Times asked current students to weigh in (helpfully labelling them “Generation Plagiarism”), and one wrote:2

“I never ‘copy and paste’ but I will take information from the Internet and change out a few words then put it in my paper. So far, I have not encountered any problems with this. Thought [sic] the information/words are technically mine because of a few undetectable word swaps, I still consider the information to be that of someone else.”3

“I’m pretty convinced that he’d still be fuzzy on plagiarism if he’d lived back when people actually used books.”

The student goes on to say that, “In the digital age, plagiarism isn’t and shouldn’t be as big of a deal as it used to be when people used books for research.” The response leaves me just as confused as I believe he is, but I’m pretty convinced that he’d still be fuzzy on plagiarism if he’d lived back when people actually used books. But what I’ve found most frustrating in the ensuing debate is the assertion that these students are a part of some new Reality Hunger-type wave of open-source everything—if every song is sampled, why shouldn’t writers do the same? The question is interesting, complicated, and divisive, but it has little bearing on a Psych 101 paper.4

Excusing plagiarism as some sort of modern-day academic mash-up won’t teach students anything more than how to lie and get away with it. We should be teaching students how to produce original work—and that there’s plenty of original thinking across the Internet—and leave the plagiarizing to the politicians.5

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

Minkel’s essay is a refutation of Trip Gabriel’s article (p. 389), whose headline she accuses of “pinpointing a problem, weaving a theory, and excusing youthful copycats in one fell swoop” (para.1). Do you agree that Gabriel’s article excuses plagiarism, or do you think it simply identifies a problem? Explain.

In paragraph 1, Minkel summarizes Gabriel’s article. Is this a fair and accurate summary?

When Minkel quotes the student in paragraphs 3 and 4, is she setting up a straw man? Why or why not?

How would you characterize Minkel’s tone? For example, is she angry? Frustrated? Condescending? Annoyed? Is this tone appropriate for her audience? (Note that this essay first appeared in the New Yorker, a magazine likely to be read by educated readers.)

In paragraph 2, Minkel identifies herself as a recent college graduate. Why? Is she appealing here to ethos, pathos, or logos?

Evaluate Minkel’s last paragraph, particularly her concluding statement. Does this paragraph accurately express her reasons for criticizing Gabriel’s article? What, if anything, do you think she should add to her conclusion? Why?

This essay appeared in Newsday on May 18, 2003.

RICHARD A. POSNER

THE TRUTH ABOUT PLAGIARISM

Plagiarism is considered by most writers, teachers, journalists, scholars, and even members of the general public to be the capital intellectual crime. Being caught out in plagiarism can blast a politician’s career, earn a college student expulsion, and destroy a writer’s, scholar’s, or journalist’s reputation. In recent days, for example, the New York Times has referred to “widespread fabrication and plagiarism” by reporter Jayson Blair as “a low point in the 152-year history of the newspaper.”1

In James Hynes’ splendid satiric novella of plagiarism, Casting the Runes, the plagiarist, having by black magic murdered one of the historians whom he plagiarized and tried to murder a second, is himself killed by the very same black magic, deployed by the widow of his murder victim.2

There is a danger of overkill. Plagiarism can be a form of fraud, but it is no accident that, unlike real theft, it is not a crime. If a thief steals your car, you are out the market value of the car, but if a writer copies material from a book you wrote, you don’t have to replace the book. At worst, the undetected plagiarist obtains a reputation that he does not deserve (that is the element of fraud in plagiarism). The real victim of his fraud is not the person whose work he copies, but those of his competitors who scruple to enhance their own reputations by such means.3

“There is a danger of overkill.”

The most serious plagiarisms are by students and professors, whose undetected plagiarisms disrupt the system of student and scholarly evaluation. The least serious are those that earned the late Stephen Ambrose and Doris Kearns Goodwin such obloquyº last year. Popular historians, they jazzed up their books with vivid passages copied from previous historians without quotation marks, though with footnote attributions that made their “crime” easy to detect.4

Abusive language

(One reason that plagiarism, like littering, is punished heavily, even though an individual act of plagiarism usually does little or no harm, is that it is normally very difficult to detect—but not in the case of Ambrose and Goodwin.) Competing popular historians might have been injured, but I’m not aware of anyone actually claiming this.5

Confusion of plagiarism with theft is one reason plagiarism engenders indignation; another is a confusion of it with copyright infringement. Wholesale copying of copyrighted material is an infringement of a property right, and legal remedies are available to the copyright holder. But the copying of brief passages, even from copyrighted materials, is permissible under the doctrine of “fair use,” while wholesale copying from material that is in the public domain—material that never was copyrighted, or on which the copyright has expired—presents no copyright issue at all.6

Plagiarism of work in the public domain is more common than otherwise. Consider a few examples: West Side Story is a thinly veiled copy (with music added) of Romeo and Juliet, which in turn plagiarized Arthur Brooke’s The Tragicall Historye of Romeo and Juliet, published in 1562, which in turn copied from several earlier Romeo and Juliets, all of which were copies of Ovid’s story of Pyramus and Thisbe.7

Paradise Lost plagiarizes the book of Genesis in the Old Testament. Classical musicians plagiarize folk melodies (think only of Dvorak, Bartok, and Copland) and often “quote” (as musicians say) from earlier classical works. Edouard Manet’s most famous painting, D é jeuner sur I’herbe, copies earlier paintings by Raphael, Titian, and Courbet, and My Fair Lady plagiarized Shaw’s play Pygmalion, while Woody Allen’s movie Play It Again, Sam “quotes” a famous scene from Casablanca. Countless movies are based on books, such as The Thirty-Nine Steps on John Buchan’s novel of that name or For Whom the Bell Tolls on Hemingway’s novel.8

Many of these “plagiarisms” were authorized, and perhaps none was deceptive; they are what Christopher Ricks in his excellent book Allusions to the Poets helpfully terms allusion rather than plagiarism. But what they show is that copying with variations is an important form of creativity, and this should make us prudent and measured in our condemnations of plagiarism.9

Especially when the term is extended from literal copying to the copying of ideas. Another phrase for copying an idea, as distinct from the form in which it is expressed, is dissemination of ideas. If one needs a license to repeat another person’s idea, or if one risks ostracism by one’s professional community for failing to credit an idea to its originator, who may be forgotten or unknown, the dissemination of ideas is impeded.10

I have heard authors of history textbooks criticized for failing to document their borrowing of ideas from previous historians. This is an absurd criticism. The author of a textbook makes no claim to originality; rather the contrary—the most reliable, if not necessarily the most exciting, textbook is one that confines itself to ideas already well accepted, not at all novel.11

It would be better if the term plagiarism were confined to literal copying, and moreover literal copying that is not merely unacknowledged but deceptive. Failing to give credit where credit is due should be regarded as a lesser, indeed usually merely venial, offense.12

The concept of plagiarism has expanded, and the sanctions for it, though they remain informal rather than legal, have become more severe, in tandem with the rise of individualism. Journal articles are no longer published anonymously, and ghostwriters demand that their contributions be acknowledged.13

Individualism and a cult of originality go hand in hand. Each of us supposes that our contribution to society is unique rather than fungibleº and so deserves public recognition, which plagiarism clouds.14

Replaceable

This is a modern view. We should be aware that the high value placed on originality is a specific cultural, and even field-specific, phenomenon, rather than an aspect of the universal moral law.15

Judges, who try to conceal rather than to flaunt their originality, far from crediting their predecessors with original thinking like to pretend that there is no original thinking in law, that judges are just a transmission belt for rules and principles laid down by the framers of statutes or the Constitution.16

Resorting to plagiarism to obtain a good grade or a promotion is fraud and should be punished, though it should not be confused with “theft.” But I think the zeal to punish plagiarism reflects less a concern with the real injuries that it occasionally inflicts than with a desire on the part of leaders of professional communities, such as journalists and historians, to enhance their profession’s reputation.17

Journalists (like politicians) have a bad reputation for truthfulness, and historians, in this “postmodernist” ° era, are suspected of having embraced an extreme form of relativism and of having lost their regard for facts. Both groups hope by taking a very hard line against plagiarism and fabrication to reassure the public that they are serious diggers after truth whose efforts, a form of “sweat equity,” deserve protection against copycats.18

Their anxieties are understandable; but the rest of us will do well to keep the matter in perspective, realizing that the term plagiarism is used loosely and often too broadly; that much plagiarism is harmless and (when the term is defined broadly) that some has social value.19

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

According to Posner, how do most people define plagiarism? How is the definition he proposes different from theirs? Do you think this definition is too broad? Too narrow?

Why does Posner believe that the plagiarisms committed by students and professors are the most serious? Can you think of an argument against this position?

How do the examples Posner cites in paragraphs 7 and 8 strengthen his argument? Do you agree that the examples he gives here constitute plagiarism? Why or why not?

Explain the connection the author makes in paragraph 16 between judges and plagiarism. (Note that Posner himself is a federal judge.)

Why, according to Posner, do journalists and historians think plagiarism should be punished severely?

According to Posner, “the truth about plagiarism” is that “much plagiarism is harmless and (when the term is defined broadly) that some has social value” (para. 19). Does the evidence he presents in this essay support this conclusion? What connection do you see between this position and his comments about the rise of individualism and the “cult of originality” in paragraphs 13–15?

This article first appeared on July 25, 2014, on Politico.com.

DYLAN BYERS

PLAGIARISM AND BUZZFEED’S ACHILLES’ HEEL

In 2013, the satirical website The Onion wrote an article titled “BuzzFeed Writer Resigns in Disgrace after Plagiarizing ‘10 Llamas Who Wish They Were Models.’” It appealed to reporters because it was a clever knock on the state of digital journalism—and because it resonated with a widely held perception about BuzzFeed.1

High-profile plagiarism cases are always met with a certain amount of schadenfreude from the media’s chattering classes, as well as calls for the defendant’s head, but the response to BuzzFeed editor Benny Johnson’s serial plagiarism has been especially intense.2

There’s a reason for that: In the eyes of many journalists, BuzzFeed is constantly walking a fine line between aggregation, or “curation,” and theft. Go to BuzzFeed.com and click on any one of its lists. In very fine print, buried below each photo, there will be a link to another site—usually Reddit—which is where the photograph came from.3

Is this plagiarism? Of course not. Does it feel a little seedy? Yeah, a bit.4

In 2012, as BuzzFeed was growing into the Internet sensation it is today, Slate ’s Farhad Manjoo (now with the New York Times) wrote a lengthy post explaining “the secret to BuzzFeed’s monster online success.”5

“How does this one site come up with so many simple ideas that people want to spread far and wide? What’s their secret?” he wrote. “The answer, in short, is that BuzzFeed’s staff finds stuff elsewhere on the Web, most often at Reddit. They polish and repackage what they find. And often—and, from what I can tell, deliberately—their posts are hard to trace back to the original source material.”6

Because BuzzFeed is so popular, Manjoo wrote, its “pilfered” lists all but eclipse the original sources of content: “Once you understand how central Reddit is to BuzzFeed, it’s like spotting the wizard behind the curtain. Whenever you see a popular BuzzFeed post, search Reddit, and all will be revealed.”7

Jonah Peretti, BuzzFeed’s founder, told Manjoo that there was “nothing wrong” with picking up other people’s content “because few things on the Web are really original.”8

Gawker’s Adrian Chen (now with the New Inquiry) also wrote an extensive analysis of BuzzFeed’s “plagiarism problem” in 2012.9

“BuzzFeed has built a lucrative business on organizing the internet’s confusing spectacle into listicles easily comprehended by even the most numbed office workers,” Chen wrote. “But the site’s approach to all content as building blocks for viral lists puts it in an awkward position in relation to internet etiquette and journalistic ethics.”10

“For example,” Chen wrote, “the BuzzFeed listicle ‘21 Pictures That Will Restore Your Faith in Humanity,’ appears to be an almost exact replica of a couple of posts on an obscure site called Nedhardy … BuzzFeed slapped together many of the same pictures, presented it as an original idea, and it went Avian-Flu-level-viral, ending up with more than seven million page views.”11

Is this plagiarism? It’s certainly closer to it. Somehow, the Internet came to accept it: The New York Times reported, Huffington Post aggregated, BuzzFeed curated. Maybe “repackaging funny things found on Reddit is just how the Internet works these days,” Chen wrote.12

Text, of course, was a different story. You couldn’t publish someone else’s articles or Wikipedia entries and just throw a link to the original source at the bottom. When BuzzFeed reporters wrote, they were subject to the same rules as everyone else. Sure you could draw facts from elsewhere—everyone does —but you had to write it in your own language.13

At some point, Johnson probably got lazy and started inserting text into his posts the same way he had been inserting photographs—by pressing Ctrl+C and Ctrl+V. His mistake was that he forgot to put quote marks around it and add “according to.”14

It didn’t help reporters’ perception of BuzzFeed that, when the first instances of plagiarism were brought to editor-in-chief Ben Smith’s attention, he called them “serious failures” of attribution, rather than “plagiarism,” and simply “corrected” the posts.15

“Ben, you can’t ‘correct’ articles that were clearly plagiarized. I know you know this!” Gawker’s J. K. Trotter wrote on Twitter.16

BuzzFeed is currently conducting an internal review of Johnson’s work before deciding on how to proceed. Whatever Johnson’s fate, his plagiarism is one more instance in which the public spotted the wizard behind BuzzFeed’s curtain. And the wizard seems a little seedy.17

“Meanwhile, The Onion’s satire has become reality.”18

“Meanwhile, The Onion’s satire has become reality.”

“Journalism today,” one Bloomberg News journalist tweeted: “accused of plagiarism ‘for an article it did about former President George H. W. Bush’s socks.’”19

Update (July 26)20

Late Friday evening Smith announced Johnson had been fired after an internal review found 40 instances of plagiarism.21

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

Do you consider the material typically posted on BuzzFeed to be plagiarized? Explain. (If you are not familiar with BuzzFeed, visit the site and read a few posts.)

What does “Achilles’ heel” mean? In what sense does plagiarism constitute BuzzFeed’s Achilles’ heel?

Why does Byers begin and end his discussion with paragraphs about The Onion (para. 1, 18–19)? Is this an effective strategy? Why or why not?

In paragraph 3, Byers says that many journalists believe that “BuzzFeed is constantly walking a fine line between aggregation, or ‘curation,’ and theft.” What distinction is he making here? Do you see a difference between BuzzFeed’s “aggregation” or “curation” and outright theft? Does Byers?

Byers quotes Farhad Manjoo, Adrian Chen, and others. What positions do his sources take on the issue of BuzzFeed and plagiarism?

Do you think it matters that Benny Johnson’s “repackaging” of material from other sources was done deliberately rather than accidentally? Why or why not?

An update to this article notes that Johnson was fired from BuzzFeed “after an internal review found 40 instances of plagiarism.” Do you think this punishment was justified? Why or why not?

Does Byers take a position on the issue of BuzzFeed and plagiarism? If so, what is that position? Do you see this essay as an argument? Which of the four elements of an argumentative essay are present here? Which are absent?

This summary was posted on July 24, 2014, on the WriteCheck.com blog.

K. BALIBALOS AND J. GOPALAKRISHNAN

OK OR NOT?

OK or not? This is an age-old question on plagiarism that arises during the writing process, whether from researching a topic, incorporating and paraphrasing sources, or supporting arguments within a paper. Students commonly find themselves in situations in which ethical questions are raised, and, all too often, students wonder whether the decisions they made were the right ones.1

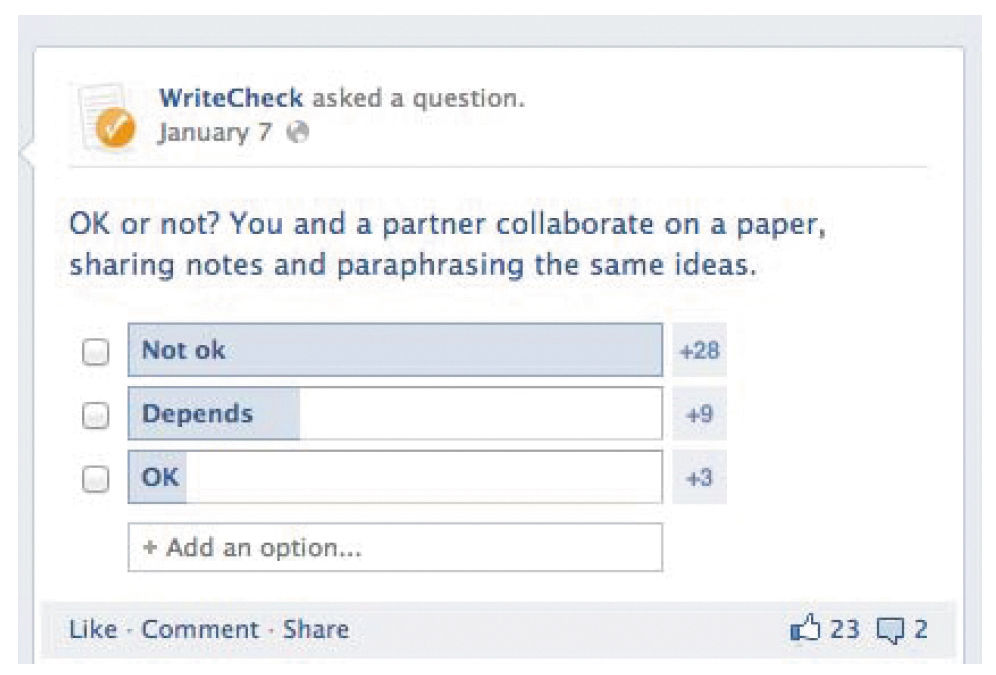

This new poll series brings to light common scenarios—specifically focused on plagiarism and perhaps a few examples on other forms of academic misconduct—and helps students better think critically about situations in order to make ethical choices. All polls can be found on the WriteCheck page on Facebook.2

POLL QUESTION #1

“OK or not? You and a partner collaborate on a paper by sharing notes and paraphrasing the same ideas.”

We started off the series by asking about collaboration because collaborating with peers is a common thing to do among students. Students “collaborate” to complete schoolwork and to help their friends in need. But collaborating with peers can sometimes cross ethical boundaries. For example, in this question, has the student copied-and-pasted the other student’s work? The question doesn’t really get into that concern, but we do know that the students shared the same ideas by “paraphrasing.” This is where the question gets tricky. If done properly, meaning the student wrote the idea in his/her own words and included citations, then paraphrasing is acceptable. Plagiarism is, by definition, the taking of another person’s work or ideas.3

The Results

The majority of respondents (28) chose “not OK” in response to student collaboration on a paper. However, two viewers who weighed in had a different perspective.4

English Instructor, Beth Calvano, made the following comment: “If the paper is supposed to be individual, this scenario is not okay. If, according to plagiarism rules, it is not acceptable to use another person’s ideas without citing that individual, collaborating in this way is not ethical. Your paper should consist of your own notes and original ideas.”5

Facebook fan Quenna Corchado agreed with Calvano, adding: “I think it’s okay if they are citing. It doesn’t matter if they are using the same sources as long as they cite it. They are helping each other out, so it makes sense that they are using the same notes and paraphrasing the same thing. What is important is to cite everything accordingly, which doesn’t make it plagiarism.”6

Overall, it can be concluded from these responses that it is “OK” to share notes and paraphrase the same idea with proper attribution, unless the assignment is supposed to be done individually.7

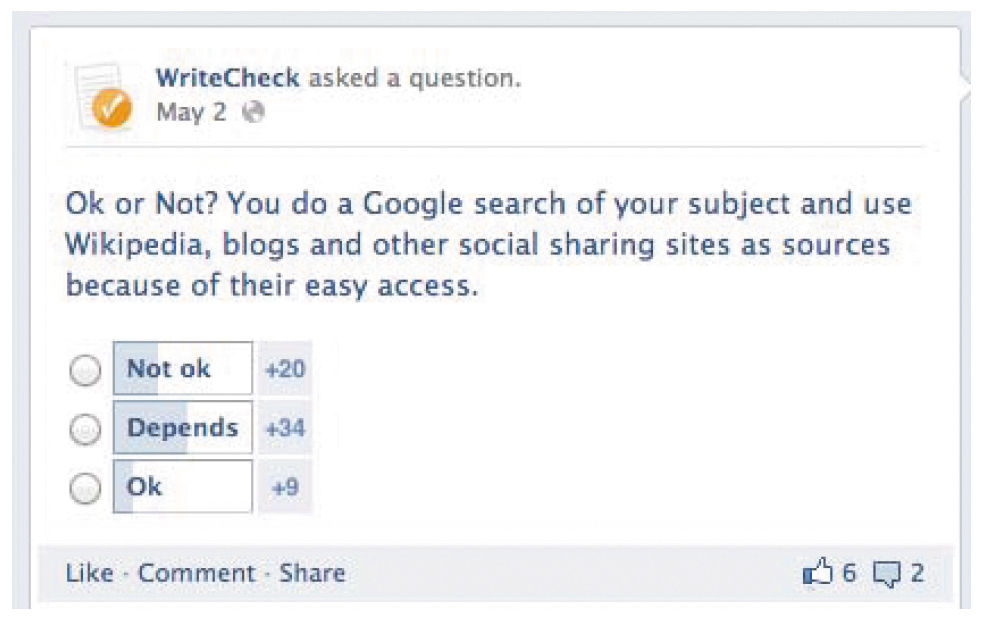

POLL QUESTION #2

“OK or not? You do a Google search of your subject and use Wikipedia,blogs, and other social sharing sites as sources because of their easy access.”

“OK or not? You do a Google search of your subject and use Wikipedia, blogs, and other social sharing sites as sources because of their easy access.”

This situation resonates with students because of the amount of free, available information due in part to the mass connectivity of the digital age. Nowadays, Wikipedia is synonymous with accessibility and reader-friendly information since it provides accurate information on nearly every topic one might be researching. The number of blogs on the internet grows exponentially by the day since anyone has the ability to create a blog and share their thoughts. And, of course, social sites are a normal part of millions of people’s lives. However, just because information is available on the web doesn’t mean that it’s reputable to use as a source in your academic paper.8

The Results

Based on 34 respondents, “depends” was the top answer, followed by “not OK” (20 respondents).9

To provide some insight, Jason Chu from Plagiarism.org weighed in with the following comment: “It’s OK to use Google search, Wikipedia, and social sharing sites as the starting point for doing research for a paper. But you should NOT rely on these sources alone. In fact, Wikipedia entries typically list references that are great to use in your research in support of your paper. But, by and large, sources that rely heavily on crowd-sourced or shared content — like Wikipedia or Yahoo! Answers — do not carry the same authority as a peer-reviewed journal article, for example.”10

Jessica from WriteCheck argued that it was “not OK,” citing educator insight that social sites should never be cited in research papers. Academic writing requires looking at primary or secondary sources, which are typically presented in academic journals, whereas Wikipedia is written for the general public.11

Overall, it can be concluded that the answer is “depends.” Social sites like Wikipedia can be used as a starting point for research papers, but adding academic credibility to your sources will result in a more thorough and scholarly research paper.12

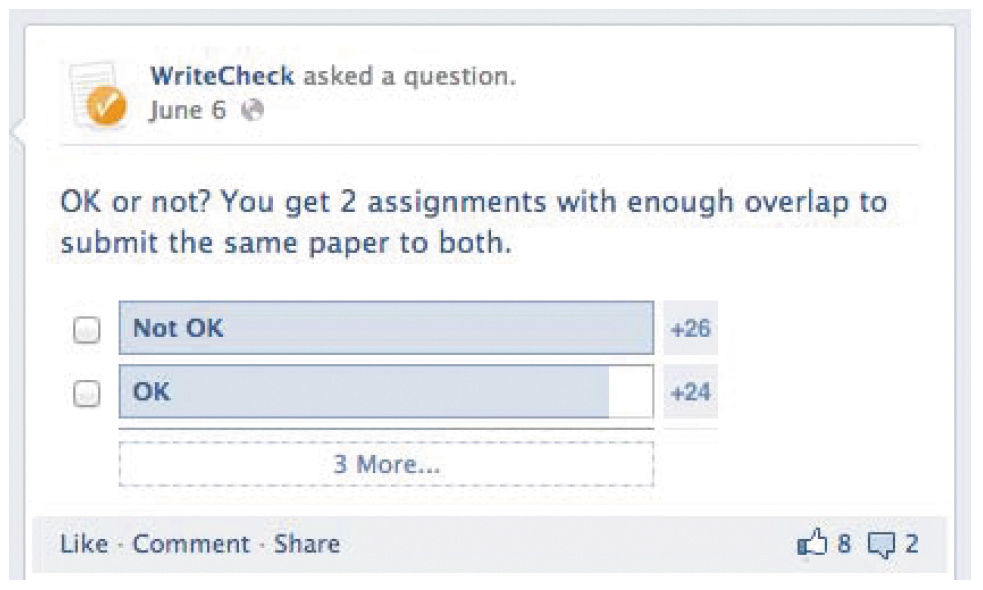

POLL QUESTION #3

“OK or not? You get 2 assignments with enough overlap to submit the same paper to both.”

The most recent poll was inspired by a recent article on the Ethicist, a blog on the New York Times, entitled, “Can I Use the Same Paper for Multiple College Courses?” Some readers see it as a stroke of genius, while others view it as the mark of laziness. Some suggest that it is cheating, while others opine that you are only cheating yourself. International Business Times writer James DiGioia disagreed with The Ethicist in his article, “The Ethicist Is Wrong: Self-Plagiarism Is Cheating.” Given those different opinions, we wanted to see what our WriteCheck community thought. “Is it ok to submit one paper for two assignments?”13

The Results

The results were evenly split among the poll respondents between “not OK” and “OK.” The Ethicist describes why this situation is tricky, explaining that emotionally, our hearts cry that “this must be unethical, somehow,” but aside from these emotions, he argued that there were no grounds that inherently make submitting papers to multiple assignments unethical.14

Unlike James DiGioia, Jason Chu of Plagiarism.org agreed somewhere in the middle, saying: “OK — if instructor approval is received. Not OK otherwise.”15

In summary, although debatable, it could be concluded that submitting a paper to multiple assignments is “OK” with approval from both instructors. Otherwise, it may be a violation of university-wide academic integrity codes and generally accepted principles that assignments are unique to a class.16

These three scenarios are real-life situations that students may face at one point in their academic journeys. Some scenarios may appear more straight-forward than others, however, no plagiarism allegation is simple. Self-plagiarism, for example, may make more sense in a professional or scholarly environment because of copyright issues. Self-plagiarism is a gray area, and a relatively new term within academia, and is still to be explored. Wikipedia also is a newly introduced site, becoming popular only within the last decade.17

While definitions and rules of plagiarism are debated, learning the definitions and how to cite properly, as well as working with instructors when a question arises are all ways to avoid plagiarism and academic misconduct.18

Have you encountered situations where you asked yourself “OK or not?”19

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

This blog post reports the results of a survey, and it also makes a point. In one sentence, summarize the main point of the post.

Which of the writers’ three scenarios, if any, do you see as “not OK”? Why? With which majority opinions, if any, do you disagree? Explain.

For what purpose did the writers design this poll? Where do they state this purpose?

Who is the intended audience for the three poll questions? Is this the same audience as the one the writers expected to read the results of the poll? How can you tell?

In poll question #2, what conclusions do the writers draw about the use of Wikipedia? What problems does this site, as well as “blogs and other social sharing sites,” present for college students?

Do you think the writers’ conclusion takes a strong enough stand on the issue discussed? Is this post actually an argument? Why or why not?

This essay originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times on June 17, 2012.

DAN ARIELY

ESSAY MILLS: A COARSE LESSON IN CHEATING

Sometimes as I decide what kind of papers to assign to my students, I worry about essay mills, companies whose sole purpose is to generate essays for high school and college students (in exchange for a fee, of course).1

The mills claim that the papers are meant to be used as reference material to help students write their own, original papers. But with names such as echeat.com, it’s pretty clear what their real purpose is.2

Professors in general are concerned about essay mills and their effect on learning, but not knowing exactly what they provide, I wasn’t sure how concerned to be. So together with my lab manager Aline Grüneisen, I decided to check the services out. We ordered a typical college term paper from four different essay mills. The topic of the paper? Cheating.3

Here is the prompt we gave the four essay mills:4

“When and why do people cheat? Consider the social circumstances involved in dishonesty, and provide a thoughtful response to the topic of cheating. Address various forms of cheating (personal, at work, etc.) and how each of these can be rationalized by a social culture of cheating.”5

We requested a term paper for a university-level social psychology class, 12 pages long, using 15 sources (cited and referenced in a bibliography). The paper was to conform to American Psychological Assn. style guidelines and needed to be completed in the next two weeks. All four of the essay mills agreed to provide such a paper, charging us in advance, between $150 and $216 for the paper.6

Right on schedule, the essays came, and I have to say that, to some degree, they allayed my fears that students can rely on the services to get good grades. What we got back from the mills can best be described as gibberish. A few of the papers attempted to mimic APA style, but none achieved it without glaring errors. Citations were sloppy. Reference lists contained outdated and unknown sources, including blog posts. Some of the links to reference material were broken.7

And the writing quality? Awful. The authors of all four papers seemed to have a very tenuous grasp of the English language, not to mention how to format an essay. Paragraphs jumped bluntly from one topic to another, often simply listing various forms of cheating or providing a long stream of examples that were never explained or connected to the “thesis” of the paper.8

“What we got back from the mills can best be described as gibberish.”

One paper contained this paragraph: “Cheating by healers. Healing is different. There is harmless healing, when healers-cheaters and wizards offer omens, lapels, damage to withdraw, the husband-wife back and stuff. We read in the newspaper and just smile. But these days fewer people believe in wizards.”9

This comes from another: “If the large allowance of study undertook on scholar betraying is any suggestion of academia and professors’ powerful yearn to decrease scholar betraying, it appeared expected these mind-set would component into the creation of their school room guidelines.”10

And finally, these gems:11

“By trusting blindfold only in stable love, loyalty, responsibility and honesty the partners assimilate with the credulous and naive persons of the past.”12

“Women have a much greater necessity to feel special.”13

“The future generation must learn for historical mistakes and develop the sense of pride and responsibility for its actions.”14

It’s hard to believe that students purchasing such papers would ever do so again.15

And the story does not end there. We submitted the four essays to WriteCheck.com, a website that inspects papers for plagiarism, and found that two of the papers were 35% to 39% copied from existing works. We decided to take action on the two papers with substantial plagiarizing and contacted the essay mills requesting our money back. Despite the solid proof we provided to them, the companies insisted they did not plagiarize. One company even threatened to expose us by calling the dean and saying we had purchased the paper.16

It’s comforting in a way that the technological revolution has not yet solved students’ problems. They still have no other option but to actually work on their papers (or maybe cheat in the old-fashioned way and copy from friends). But I do worry about the existence of essay mills and the signal that they send to our students.17

As for our refund, we are still waiting.18

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

Consider the title of this essay. What does the word coarse mean? What does it suggest in this context?

What is an essay mill? Look up the word mill. Which of the definitions provided applies to the word as it is used in the phrase essay mill?

Why does Ariely decide to investigate the services provided by essay mills? What does he want to find out? Is he successful?

What does Ariely conclude about the four companies he surveys? Does he provide enough evidence to support his conclusion? If not, what kind of evidence should he add?

In paragraph 15, Ariely says, “It’s hard to believe that students purchasing such papers would ever do so again.” Given the evidence Ariely pre sents, how do you explain the continued popularity of essay mills?

What information does Ariely provide in his conclusion? Do you think he is departing from his essay’s central focus here, or do you think the concluding paragraph is an appropriate and effective summary of his ideas? Explain.

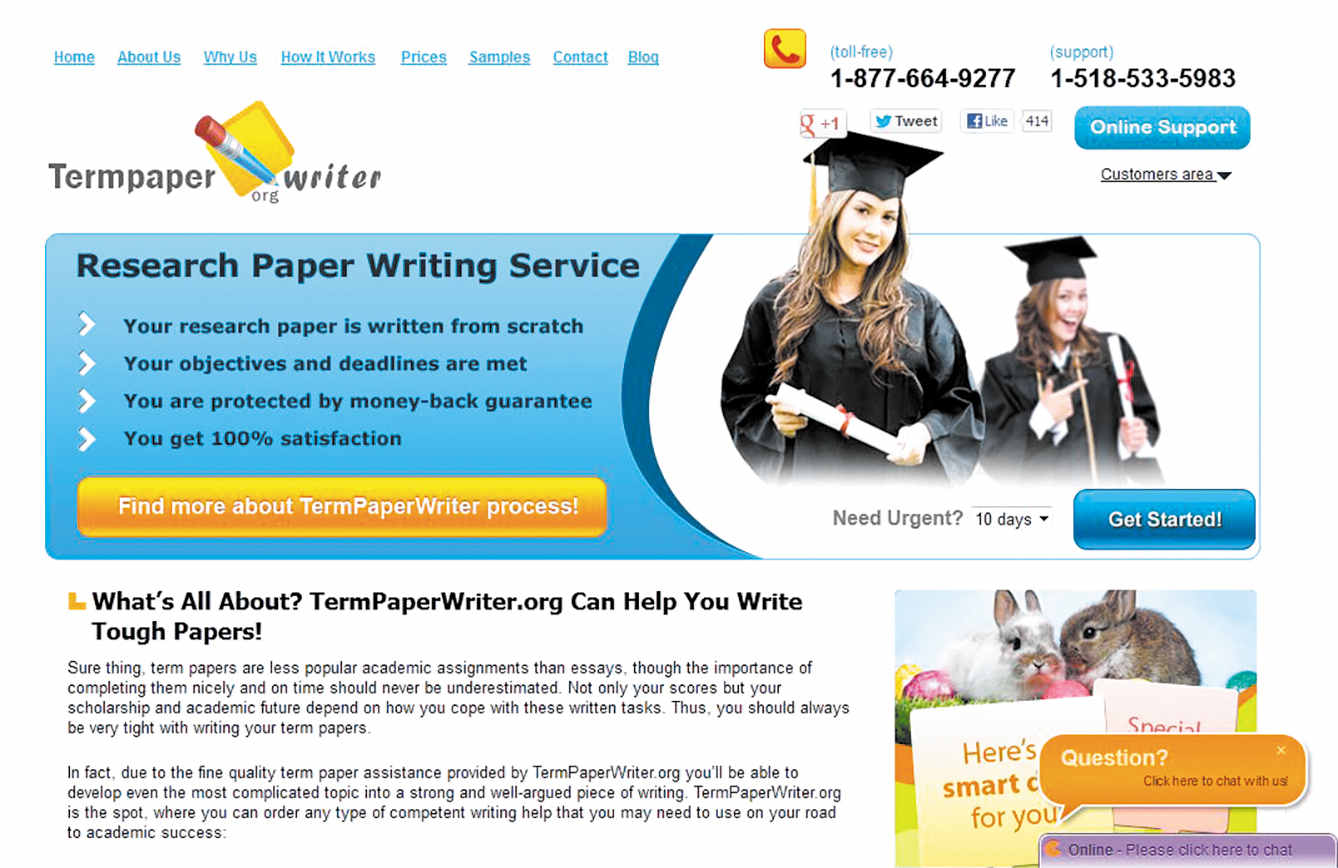

TERM PAPERS FOR SALE ADVERTISEMENT (WEB PAGE)

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR UNDERSTANDING PLAGIARISM

The Web page above is from a site that offers papers for sale to students. What argument does this Web page make? What counterargument could you present?

Identify appeals to logos, pathos, and ethos on the TermPaperWriter.org page. Which appeal dominates?

Study the images of students on the page. What message do these images convey?

Unlike the TermPaperWriter.org page, many other sites that offer papers for sale include errors in grammar, spelling, and punctuation. Search the Web for some other sites that offer papers for sale. What errors can you find? Do such errors weaken the message of these ads, or are they irrelevant?

One site promises its papers are “100% plagiarism free.” Does this promise make sense? Explain.

TEMPLATE FOR WRITING AN ARGUMENT ABOUT PLAGIARISM

Write a one-paragraph argument in which you take a position on where to draw the line with plagiarism. Follow the template below, filling in the blanks to create your argument.

To many people, plagiarism is theft; to others, however, it is not that simple. For example, some define plagiarism as ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________; others see it as _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________. Another thing to consider is _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________. In addition, ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________. Despite these differences of opinion, plagiarism is often dealt with harshly and can ruin careers and reputations. All things considered, ________________________________________________________________________________.

EXERCISE 11.4

EXERCISE 11.4

Discuss your feelings about plagiarism with two or three of your class-mates. Consider how you define plagiarism, what you believe causes it, whether there are degrees of dishonesty, and so on, but focus on the effects of plagiarism—on those who commit it and on those who are its victims. Then, write a paragraph that summarizes the key points of your discussion.

EXERCISE 11.5

EXERCISE 11.5

Write an argumentative essay on the topic, “Where Should We Draw the Line with Plagiarism?” Begin by defining what you mean by plagiarism, and then narrow your discussion down to a particular group—for example, high school or college students, historians, scientists, or journalists. Cite the sources on pages 383–409, and be sure to document the sources you use and to include a works-cited page. (See Chapter 10 for information on documenting sources.)

EXERCISE 11.6

EXERCISE 11.6

Review the four pillars of argument discussed in Chapter 1. Does your essay include all four elements of an effective argument? Add anything that is missing. Then, label the elements of your argument.

WRITING ASSIGNMENTS: USING SOURCES RESPONSIBLY

WRITING ASSIGNMENTS: USING SOURCES RESPONSIBLY

Write an argument in which you take a position on who (or what) is to blame for plagiarism among college students. Is plagiarism always the student’s fault, or are other people (or other factors) at least partly to blame?

Write an essay in which you argue that an honor code will (or will not) eliminate (or at least reduce) plagiarism and other kinds of academic dishonesty at your school.

Reread the essays by Posner and Balibalos and Gopalakrishnan in this chapter. Then, write an argument in which you argue that only intentional plagiarism should be punished.

Do you consider student plagiarism a victimless crime that is best left unpunished? If so, why? If not, how does it affect its victims—for example, the student who plagiarizes, the instructor, the other students in the class, and the school?