Evaluating Sources

Whenever you locate a source—print or electronic—you should always take the time to evaluate it. When you evaluate a source, you assess the objectivity of the author, the credibility of the source, and its relevance to your argument. (Although a librarian or an instructor has screened the print and electronic sources in your college library for general accuracy and trustworthiness, you cannot simply assume that these sources are suitable for your particular writing project.)

Sources must be evaluated carefully.

©Viorika Prikhodko/iStock/Getty Images

Material that you access online presents particular problems. Because anyone can publish on the Internet, the information you find there has to be evaluated carefully for accuracy. Although some material on the Internet (for example, journal articles that are published in both print and digital format) is reliable, other material (for example, personal websites and blogs) may be unreliable and unsuitable for your research. To be reasonably certain that the information you are accessing is appropriate, you have to approach it critically.

As you locate sources, make sure that they are suitable for your research. (Remember, if you use an untrustworthy source, you undercut your credibility.)

To evaluate sources, you use the same process that you use when you evaluate anything else. For example, if you are thinking about buying a laptop computer, you use several criteria to help you make your decision—for example, price, speed, memory, reliability, and availability of technical support. The same is true for evaluating research sources. You can use the following criteria to decide whether a source is appropriate for your research:

Accuracy

Credibility

Objectivity

Currency

Comprehensiveness

Authority

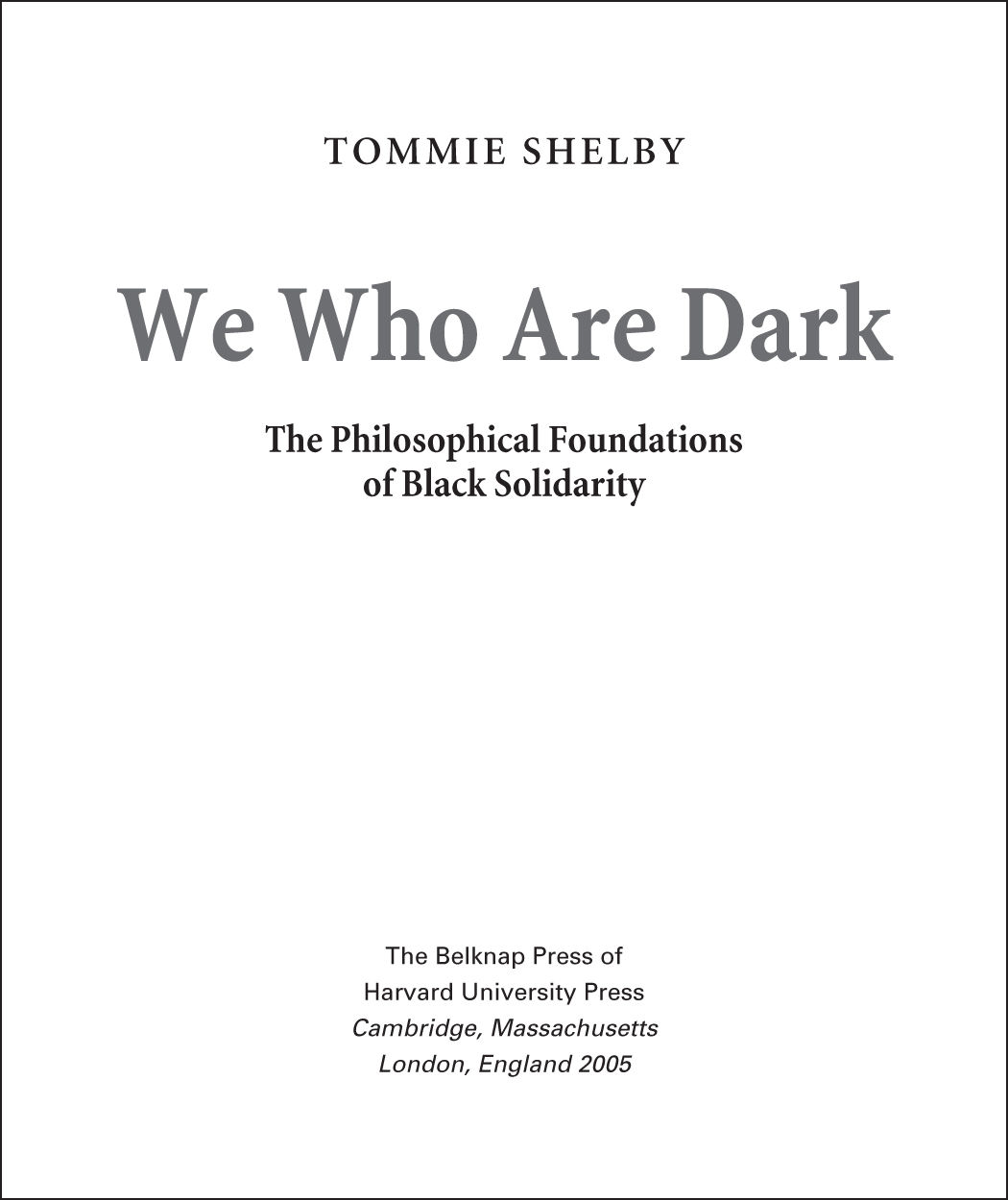

The illustrations on page 293 show where to find information that can help you evaluate a source.

Accuracy

A source is accurate when it is factual and free of errors. One way to judge the accuracy of a source is to compare the information it contains to that same information in several other sources. If a source has factual errors, then it probably includes other types of errors as well. Needless to say, errors in spelling and grammar should also cause you to question a source’s general accuracy.

You can also judge the accuracy of a source by checking to see if the author cites sources for the information that is discussed. Documentation can help readers determine both the quality of information in a source and the range of sources used. It can also show readers what sources a writer has failed to consult. (Failure to cite an important book or article should cause you to question the writer’s familiarity with a subject.) If possible, verify the legitimacy of some of the books and articles that a writer cites by seeing what you can find out about them online. If a source has caused a great deal of debate or if it is disreputable, you will probably be able to find information about the source by researching it on Google.

Credibility

A source is credible when it is believable. You can begin checking a source’s credibility by determining where a book or article was published. If a university press published the book, you can be reasonably certain that it was peer reviewed —read by experts in the field to confirm the accuracy of the information. If a commercial press published the book, you will have to consider other criteria—the author’s reputation and the date of publication, for example—to determine quality. If your source is an article, see if it appears in a scholarly journal —a periodical aimed at experts in a particular field—or in a popular magazine —a periodical aimed at general readers. Journal articles are almost always acceptable research sources because they are usually documented, peer reviewed, and written by experts. (They can, however, be difficult for general readers to understand.) Articles in high-level popular magazines, such as the Atlantic and the Economist, may also be suitable—provided experts wrote them. However, articles in lower-level popular magazines—such as Sports Illustrated and Time —may be easy to understand, but they are seldom acceptable sources for research.

You can determine how well respected a source is by reading reviews written by critics. You can find reviews of books by consulting Book Review Digest —either in print or online—which lists books that have been reviewed in at least three magazines or newspapers and includes excerpts of reviews. In addition, you can consult the New York Times Book Review website—www.nytimes.com/pages/books/index.html—to access reviews printed by the newspaper since 1981. (Both professional and reader reviews are also available at Amazon.com.)

Finally, you can determine how well respected a source is by seeing how often other scholars in the field refer to it. Citation indexes indicate how often books and articles are mentioned by other sources in a given year. This information can give you an idea of how important a work is in a particular field. Citation indexes for the humanities, the social sciences, and the sciences are available online and in your college library.

Objectivity

A source is objective when it is not unduly influenced by personal opinions or feelings. Ideally, you want to find sources that are objective, but to one degree or another, all sources are biased. In short, all sources—especially those that take a stand on an issue—reflect the opinions of their authors, regardless of how hard they may try to be impartial. (Of course, an opinion is perfectly acceptable—as long as it is supported by evidence.)

As a researcher, you should recognize that bias exists and ask yourself whether a writer’s assumptions are justified by the facts or are simply the result of emotion or preconceived ideas. You can make this determination by looking at a writer’s choice of words and seeing if the language is slanted or by reviewing the writer’s points and seeing if his or her argument is one-sided. Get in the habit of asking yourself whether you are being offered a legitimate point of view or simply being fed propaganda.

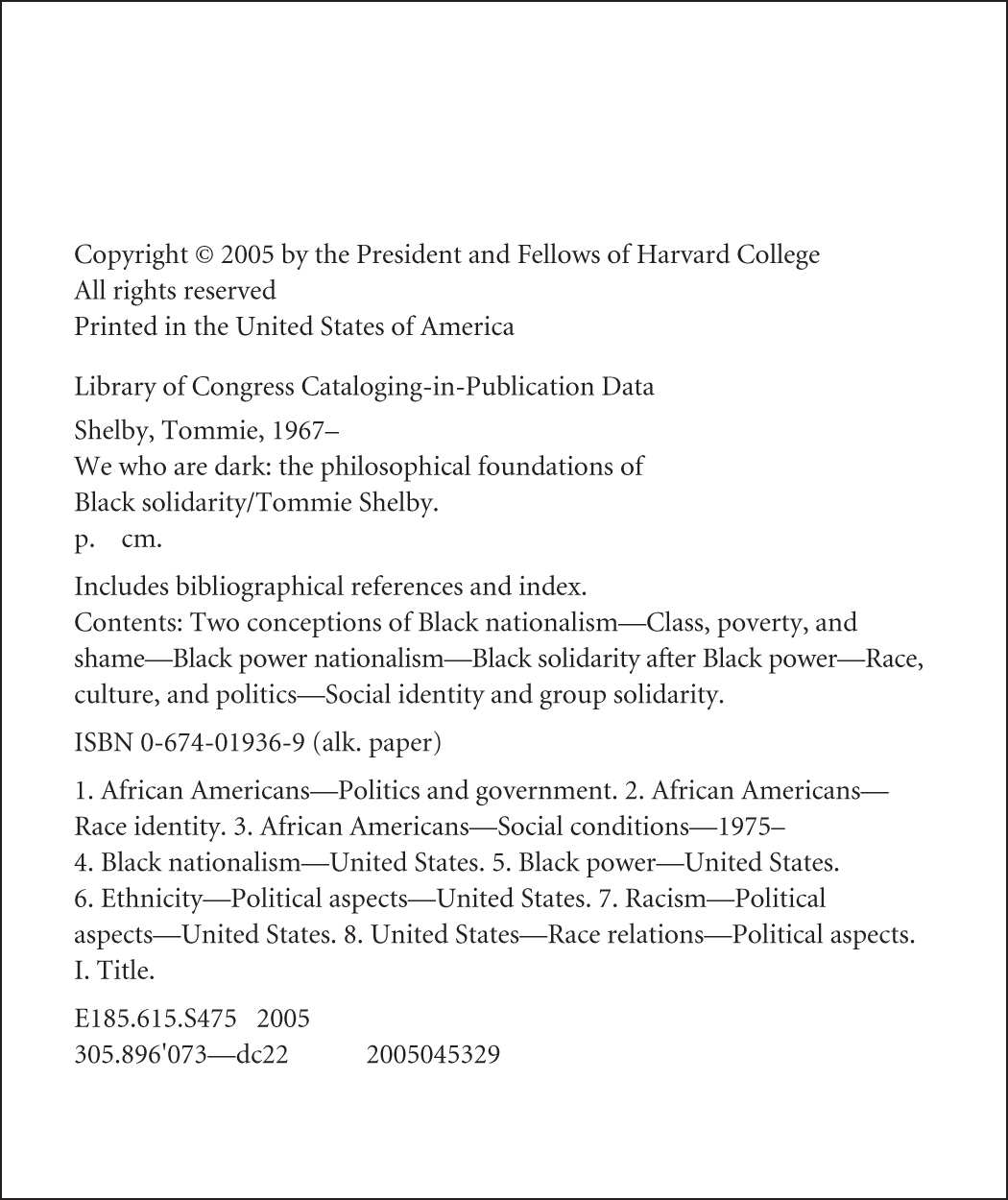

The covers of the liberal and conservative magazines shown here suggest different biases.

© Roz Chast/The New Yorker

The covers of the liberal and conservative magazines shown here suggest different biases.

© Yasamin Khalili/Townhall Magazine

Currency

A source is current when it is up-to-date. (For a book, you can find the date of publication on the copyright page, as above. For an article, you can find the date on the front cover of the magazine or journal.) If you are dealing with a scientific subject, the date of publication can be very important. Older sources might contain outdated information, so you want to use the most up-to-date source that you can find. For other subjects—literary criticism, for example—the currency of the information may not be as important as it is in the sciences.

Comprehensiveness

A source is comprehensive when it covers a subject in sufficient depth. The first thing to consider is whether the source deals specifically with your subject. (If it treats your subject only briefly, it will probably not be useful.) Does it treat your subject in enough detail? Does the source include the background information that you need to understand the discussion? Does the source mention other important sources that discuss your subject? Are facts and interpretations supported by the other sources you have read, or are there major points of disagreement? Finally, does the author include documentation?

How comprehensive a source needs to be depends on your purpose and audience as well as on your writing assignment. For a short essay for an introductory course, editorials from the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal might give you enough information to support your argument. If you are writing a longer essay, however, you might need to consult journal articles (and possibly books) about your subject.

Authority

A source has authority when a writer has the expertise to write about a subject. Always try to determine if the author is a recognized authority or simply a person who has decided to write about a particular topic. For example, what other books or articles has the author written? Has your instructor ever mentioned the author’s name? Is the author mentioned in your textbook? Has the author published other works on the same subject or on related subjects? (You can find this information on Amazon.com.)

You should also determine if the author has an academic affiliation. Is he or she a faculty member at a respected college or university? Do other established scholars have a high opinion of the author? You can often find this information by using a search engine such as Google or by consulting one of the following directories:

Contemporary Authors

Directory of American Scholars

International Who’s Who

National Faculty Directory

Who’s Who in America

Wilson Biographies Plus Illustrated

USA TODAY Editorial Board

TIME TO ENACT “DO NOT TRACK”

Facebook’s 800 million users are probably feeling a little more secure since the social media giant agreed to privacy measures forced by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) late last month. But they’d be wise to stay cautious. Plenty of incentive for mischief remains, and not only on Facebook.1

The agreement requires Facebook to stop letting users mark their profile information as private and then making it public without their permission. Facebook also promised that it will warn users of privacy policy changes before enacting them.2

But the agreement won’t stop Facebook from monitoring and sharing users’ Web-browsing habits, which is a way for the company and others like it to make money. It’s an unsatisfying ending to a two-year investigation, but more important, it’s a marker of how difficult it will be to maintain privacy in an increasingly wired world.3

The weakness in the FTC’s agreement is that it didn’t establish any guidelines about Internet tracking, the method by which Facebook collects data about its users even when they’re not on the network itself. As company representatives recently acknowledged to USA Today, Facebook automatically compiles a log of every Web page its users visit that has a Facebook plug-in, such as the ubiquitous “like” button.4

Other online giants, such as Google and Yahoo, use similar methods to monitor users’ Web-browsing. This lets them tailor their pages and advertisements to appeal to different visitors.5

Online tracking companies, which help sites compile these browsing records, claim that your personal details are not connected to your name, meaning your privacy is not compromised when they share information with advertisers or others. But as the Wall Street Journal discovered last year, at least one tracking company collected Web surfers’ names and other personally identifiable information and passed it on to clients.6

The implication is that tracking companies and advertisers could know your name, e-mail address, hometown, medical history, political affiliation, and more. Such information could be used in troubling ways. A health insurance company, for example, could guess your medical conditions. Or a potential employer could find out whether you spend your time gambling online.7

“Such information could be used in troubling ways.”

If you don’t like that prospect, your only option is to use a Web browser that offers a “Do Not Track” mechanism, such as Mozilla Firefox or Internet Explorer 9. Once you activate the feature, it signals websites you visit indicating that you do not want your data tracked by third parties. But existing Do Not Track mechanisms can’t control what websites do; they can only communicate your preference.8

That’s why the FTC has called for a tougher and more universal version of Do Not Track, a move that the online advertising industry argues would hamper Internet innovation. These fears are overblown. Behavioral advertising, which targets viewers based on their Web-browsing history, is large and growing, but it still accounts for less than 5% of all online advertising. So ads that rely on tracking are hardly the Internet’s only revenue stream.9

Measures that would create a legally enforceable Do Not Track mechanism or otherwise address privacy concerns are languishing in Congress. Lawmakers should give Web users more tools to control their personal information. Until that happens, your online habits will reveal much more about you than just what you put on your Facebook profile.10

This essay is from MacKinnon’s book Consent of the Networked (2012).

REBECCA MACKINNON

PRIVACY AND FACEBOOK

As protests mounted in reaction to Iran’s presidential elections on June 12, 2009, Facebook actively encouraged members of the pro-opposition Green Movement to use the social networking platform. By mid-June, more than four hundred members of Facebook’s fast-growing Farsi-speaking community volunteered their time to create a Farsi version of Facebook. Thanks to efforts by Facebook enthusiasts all around the world, the platform has been made accessible in seventy languages—including many languages spoken in countries where regimes are known not to tolerate dissent.1

Then in December 2009, Facebook made a sudden and unexpected alteration of its privacy settings. On December 9, to be precise, people who logged in got an automatic pop-up message announcing major changes. Until that day, it was possible to keep one’s list of Facebook “friends” hidden not only from the general Internet-surfing public but also from one another. That changed overnight without warning. An array of information that Facebook previously had treated as private, suddenly and without warning became publicly available information by default. This included a user’s profile picture, name, gender, current city, what professional and regional “networks” one belonged to within Facebook, the “causes” one had signed on to support, and one’s entire list of Facebook friends.2

The changes were driven by Facebook’s need to monetize the service but were also consistent with founder Mark Zuckerberg’s strong personal conviction that people everywhere should be open about their lives and actions. In Iran, where authorities were known to be using information and contacts obtained from people’s Facebook accounts while interrogating Green Movement activists detained from the summer of 2009 onward, the implications of the new privacy settings were truly frightening. Soon after the changes were made, an anonymous commenter on the technology news site ZDNet confirmed that Iranian users were deleting their accounts in horror:3

A number of my friends in Iran are active student protesters of the government. They use Facebook extensively to organize protests and meetings, but they had no choice but to delete their Facebook accounts today. They are terrified that their once private lists of friends are now available to “everyone” that wants to know. When that “everyone” happens to include the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and members of the Basij militia, willing to kidnap, arrest, or murder to stifle dissent, the consequences seem just a bit more serious than those faced from silly pictures and status updates. I realize this may not be an issue for the vast majority of American Facebook users, but it’s just plain irresponsible to do this without first asking consent. It’s even more egregious because Facebook threw out the original preference (the one that requested Facebook keep the list of friends private) and replaced it with a mandate, publicizing what was once private information—with no explicit consent. If given the choice to remain a Facebook user with those settings, or quit, my friends would have quit rather than risk that information being seen by the wrong people. Instead, Facebook published it anyways. It’s a betrayal of trust for the sake of better targeted advertising.

The global outcry over the exposure of people’s friend lists in December 2009 was so strong that within roughly a day after the dramatic change, Facebook made an adjustment so that users could once again hide their friend lists from public view. People’s friends could still see one another, however, and there was no way to hide them. Everybody’s “causes” and “pages” were still publicly exposed by default, another serious vulnerability for activists. People kept complaining—many by creating protest groups within Facebook itself, where hundreds of thousands of people from all around the world posted angry messages. The groups had names like “Facebook! Fix the Privacy Settings!” and “Hide Friend List and Fan Pages! We Need Better Privacy Controls!” and “We Want Our Old Privacy Settings Back!” Scrolling through these pages, you see people posting from all over the world, with large numbers of Arab, Persian, Turkish, Eastern European, and Chinese names.4

“People’s friends could still see one another, however, and there was no way to hide them.”

Eventually Facebook fixed this problem as well, adjusting the privacy options so that information about what pages users follow, or groups they have joined, can be made private. Meanwhile, however, lives of people around the world had been endangered unnecessarily—not because any government pressured Facebook to make changes, but because Facebook had its own reasons and did not fully consider the implications for the service’s most vulnerable users, in democratic and authoritarian countries alike.5

EXERCISE 8.2

EXERCISE 8.2

Write a one-or two-paragraph evaluation of each of the three sources you read for Exercise 8.1. Be sure to support your evaluation with specific references to the sources.

Evaluating Websites

The Internet is like a freewheeling frontier town in the old West. Occasionally, a federal marshal may pass through, but for the most part, there is no law and order, so you are on your own. On the Internet, literally anything goes—exaggerations, misinformation, errors, and even complete fabrications. Some websites contain reliable content, but many do not. The main reason for this situation is that there is no authority—as there is in a college library—who evaluates sites for accuracy and trustworthiness. That job falls to you, the user.

Another problem is that websites often lack important information. For example, a site may lack a date, a sponsoring organization, or even the name of the author of the page. For this reason, it is not always easy to evaluate the material you find there.

Most sources found in a college library have been evaluated by a reference librarian for their suitability as research sources.

© Steve Hix/Somos Images/Corbis

When you evaluate a website (especially when it is in the form of a blog or a series of posts), you need to begin by viewing it skeptically—unless you know for certain that it is reliable. In other words, assume that its information is questionable until you establish that it is not. Then apply the same criteria you use to evaluate any sources—accuracy, credibility, objectivity, currency, comprehensiveness, and authority.

The Web page pictured on page 303 shows where to find information that can help you evaluate a website.

Accuracy

Information on a website is accurate when it is factual and free of errors. Information in the form of facts, opinions, statistics, and interpretations is everywhere on the Internet, and in the case of Wiki sites, this information is continually being rewritten and revised. Given the volume and variety of this material, it is a major challenge to determine its accuracy. You can assess the accuracy of information on a website by asking the following questions:

Does the site contain errors of fact? Factual errors—inaccuracies that relate directly to the central point of the source—should immediately disqualify a site as a reliable source.

Does the site contain a list of references or any other type of documentation? Reliable sources indicate where their information comes from. The authors know that people want to be sure that the information they are using is accurate and reliable. If a site provides no documentation, you should not trust the information it contains.

Does the site provide links to other sites? Does the site have links to reliable websites that are created by respected authorities or sponsored by trustworthy institutions? If it does, then you can conclude that your source is at least trying to maintain a certain standard of quality.

Can you verify information? A good test for accuracy is to try to verify key information on a site. You can do this by checking it in a reliable print source or on a good reference website such as Encyclopedia.com.

Credibility

Information on a website is credible when it is believable. Just as you would not naively believe a stranger who approached you on the street, you should not automatically believe a site that you randomly encounter on the Web. You can assess the credibility of a website by asking the following questions:

Does the site list authors, directors, or editors? Anonymity—whether on a website or on a blog—should be a red flag for a researcher who is considering using a source.

Is the site refereed? Does a panel of experts or an advisory board decide what material appears on the website? If not, what standards are used to determine the suitability of content?

Does the site contain errors in grammar, spelling, or punctuation? If it does, you should be on the alert for other types of errors. If the people maintaining the site do not care enough to make sure that the site is free of small errors, you have to wonder if they will take the time to verify the accuracy of the information presented.

Does an organization sponsor the site? If so, do you know (or can you find out) anything about the sponsoring organization? Use a search engine such as Google to determine the purpose and point of view of the organization.

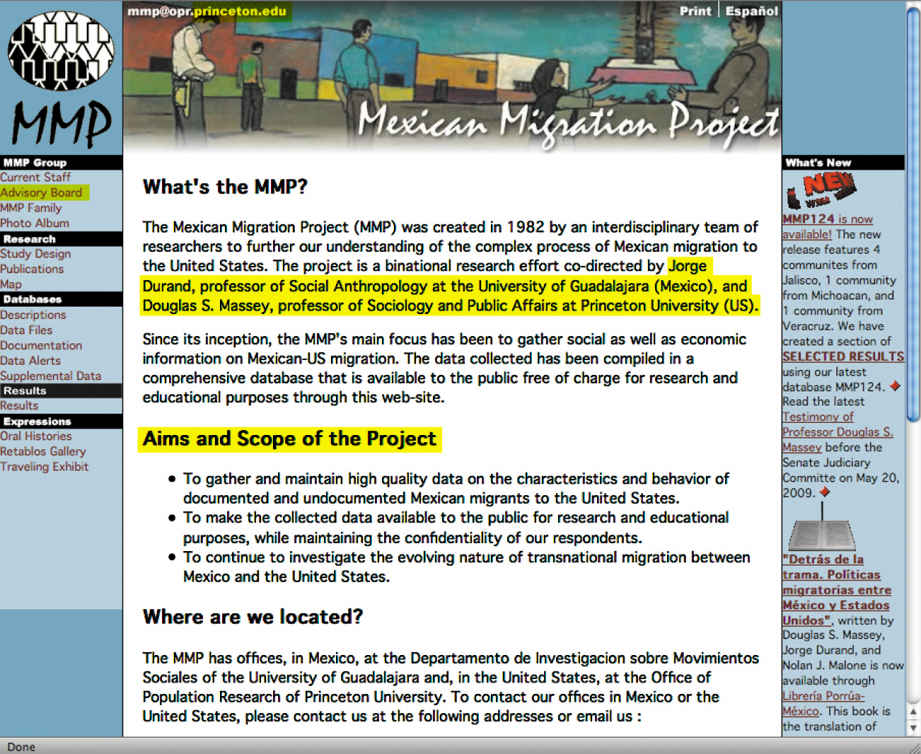

Courtesy from the Mexican Migration Project, mmp.opr.princeton.edu.

On the top of the page in the extreme left is written ‘mmp@opr.princeton.edu’ where ‘princeton.edu’ is highlighted in yellow color marked by a line as the ‘Sponsoring Organization’. In the left hand column on the page, there is a logo and MMP is written below it in Capital letters. There is column that says MMP Group in black highlights and states ‘Current Staff’, ‘Advisory Board’, ‘MMP Family’ and ‘Photo Album’ in the same column. ‘Advisory Board’ is highlighted in yellow and marked by a line that says ‘Advisory Board’. The main text of the page is titled as ‘What’s the MMP? The paragraph below the title states ‘The Mexican Migration Project (MMP) was created in 1982 by an interdisciplinary team of researchers to further our understanding of the complex process of Mexican migration to the United States. The project is a national research effort co-directed by Jorge Durand, professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Guadalajara (Mexico), and Douglas S. Massey, professor of Sociology and Public Affairs at Princeton University(US). In this paragraph, Jorge Durand, professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Guadalajara (Mexico), and Douglas S. Massey, professor of Sociology and Public Affairs at Princeton University(US) is highlighted in yellow and marked as ‘Directors of site’ by a line. The second paragraph states the ‘Aims and Scope of the Project’ which is highlighted in yellow color. There are three points below it. The first point is ‘To gather and maintain high quality data on the characteristics and behaviour of documented and undocumented Mexican migrants to the United States’. The second point is ‘To make the collected data available to the public for research and educational purposes, while maintaining the confidentiality of our respondents’. The third point is ‘To continue to investigate the evolving nature of transnational migration between Mexico and the United States’. All of these three points are jointly marked by a line as ‘Goals of project’ The last paragraph on the page is titled as ‘Where we are located?’

Objectivity

Information on a website is objective when it limits the amount of bias that it displays. Some sites—such as those that support a particular political position or social cause—make no secret of their biases. They present them clearly in their policy statements on their home pages. Others, however, try to hide their biases—for example, by referring only to sources that support a particular point of view and not mentioning those that do not.

Keep in mind that bias does not automatically disqualify a source. It should, however, alert you to the fact that you are seeing only one side of an issue and that you will have to look further to get a complete picture. You can assess the objectivity of a website by asking the following questions:

Does advertising appear on the site? If the site contains advertising, check to make sure that the commercial aspect of the site does not affect its objectivity. The site should keep advertising separate from content.

Does a commercial entity sponsor the site? A for-profit company may sponsor a website, but it should not allow commercial interests to determine content. If it does, there is a conflict of interest. For example, if a site is sponsored by a company that sells organic products, it may include testimonials that emphasize the virtues of organic products and ignore information that is skeptical of their benefits.

Does a political organization or special-interest group sponsor the site? Just as you would for a commercial site, you should make sure that the sponsoring organization is presenting accurate information. It is a good idea to check the information you get from a political site against information you get from an educational or a reference site—Ask.com or Encyclopedia.com, for example. Organizations have specific agendas, and you should make sure that they are not bending the truth to satisfy their own needs.

Does the site link to strongly biased sites? Even if a site seems trustworthy, it is a good idea to check some of its links. Just as you can judge people by the company they keep, you can also judge websites by the sites they link to. Links to overly biased sites should cause you to reevaluate the information on the original site.

USING A SITE’S URL TO ASSESS ITS OBJECTIVITY

A website’s URL (uniform resource locator) can give you information that can help you assess the site’s objectivity.

Look at the domain name to identify sponsorship. Knowing a site’s purpose can help you determine whether a site is trying to sell you something or just trying to provide information. The last part of a site’s URL can tell you whether a site is a commercial site (.com and .net), an educational site (.edu), a nonprofit site (.org), or a governmental site (.gov, .mil, and so on).

See if the URL has a tilde (~) in it. A tilde in a site’s URL indicates that information was published by an individual and is unaffiliated with the sponsoring organization. Individuals can have their own agendas, which may be different from the agenda of the site on which their information appears or to which it is linked.

AVOIDING CONFIRMATION BIAS

Confirmation bias is a tendency that people have to accept information that supports their beliefs and to ignore information that does not. For example, people see false or inaccurate information on websites, and because it reinforces their political or social beliefs, they forward it to others. Eventually, this information becomes so widely distributed that people assume that it is true. Numerous studies have demonstrated how prevalent confirmation bias is. Consider the following examples:

A student doing research for a paper chooses sources that support her thesis and ignores those that take the opposite position.

A prosecutor interviews witnesses who establish the guilt of a suspect and overlooks those who do not.

A researcher includes statistics that confirm his hypothesis and excludes statistics that do not.

When you write an argumentative essay, do not accept information just because it supports your thesis. Realize that you have an obligation to consider all sides of an issue, not just the side that reinforces your beliefs.

Currency

Information on a website is current when it is up-to-date. Some sources—such as fiction and poetry—are timeless and therefore are useful whatever their age. Other sources, however—such as those in the hard sciences—must be current because advances in some disciplines can quickly make information outdated. For this reason, you should be aware of the shelf life of information in the discipline you are researching and choose information accordingly. You can assess the currency of a website by asking the following questions:

Does the website include the date when it was last updated? As you look at Web pages, check the date on which they were created or updated. (Some websites automatically display the current date, so be careful not to confuse this date with the date the page was last updated.)

Are all links on the site live? If a website is properly maintained, all the links it contains will be live —that is, a click on the link will take you to other websites. If a site contains a number of links that are not live, you should question its currency.

Is the information on the site up-to-date? A site might have been updated, but this does not necessarily mean that it contains the most up-to-date information. In addition to checking when a website was last updated, look at the dates of the individual articles that appear on the site to make sure they are not outdated.

Comprehensiveness

Information on a website is comprehensive when it covers a subject in depth. A site that presents itself as a comprehensive source should include (or link to) the most important sources of information that you need to understand a subject. (A site that leaves out a key source of information or that ignores opposing points of view cannot be called comprehensive.) You can assess the comprehensiveness of a website by asking the following questions:

Does the site provide in-depth coverage? Articles in professional journals—which are available both in print and online—treat subjects in enough depth for college-level research. Other types of articles—especially those in popular magazines and in general encyclopedias, such as Wikipedia —are often too superficial (or untrustworthy) for college-level research.

Does the site provide information that is not available elsewhere? The website should provide information that is not available from other sources. In other words, it should make a contribution to your knowledge and do more than simply repackage information from other sources.

Who is the intended audience for the site? Knowing the target audience for a website can help you to assess a source’s comprehensiveness. Is it aimed at general readers or at experts? Is it aimed at high school students or at college students? It stands to reason that a site that is aimed at experts or college students will include more detailed information than one that is aimed at general readers or high school students.

Authority

Information on a website has authority when you can establish the legitimacy of both the author and the site. You can determine the authority of a source by asking the following questions:

Is the author an expert in the field that he or she is writing about? What credentials does the author have? Does he or she have the expertise to write about the subject? Sometimes you can find this information on the website itself. For example, the site may contain an “About the Author” section or links to other publications by the author. If this information is not available, do a Web search with the author’s name as a keyword. If you cannot confirm the author’s expertise (or if the site has no listed author), you should not use material from the site.

What do the links show? What information is revealed by the links on the site? Do they lead to reputable sites, or do they take you to sites that suggest that the author has a clear bias or a hidden agenda? Do other reliable sites link back to the site you are evaluating?

Is the site a serious publication? Does it include information that enables you to judge its legitimacy? For example, does it include a statement of purpose? Does it provide information that enables you to determine the criteria for publication? Does the site have a board of advisers? Are these advisers experts? Does the site include a mailing address and a phone number? Can you determine if the site is the domain of a single individual or the effort of a group of individuals?

Does the site have a sponsor? If so, is the site affiliated with a reputable institutional sponsor, such as a governmental, educational, or scholarly organization?

EXERCISE 8.3

EXERCISE 8.3

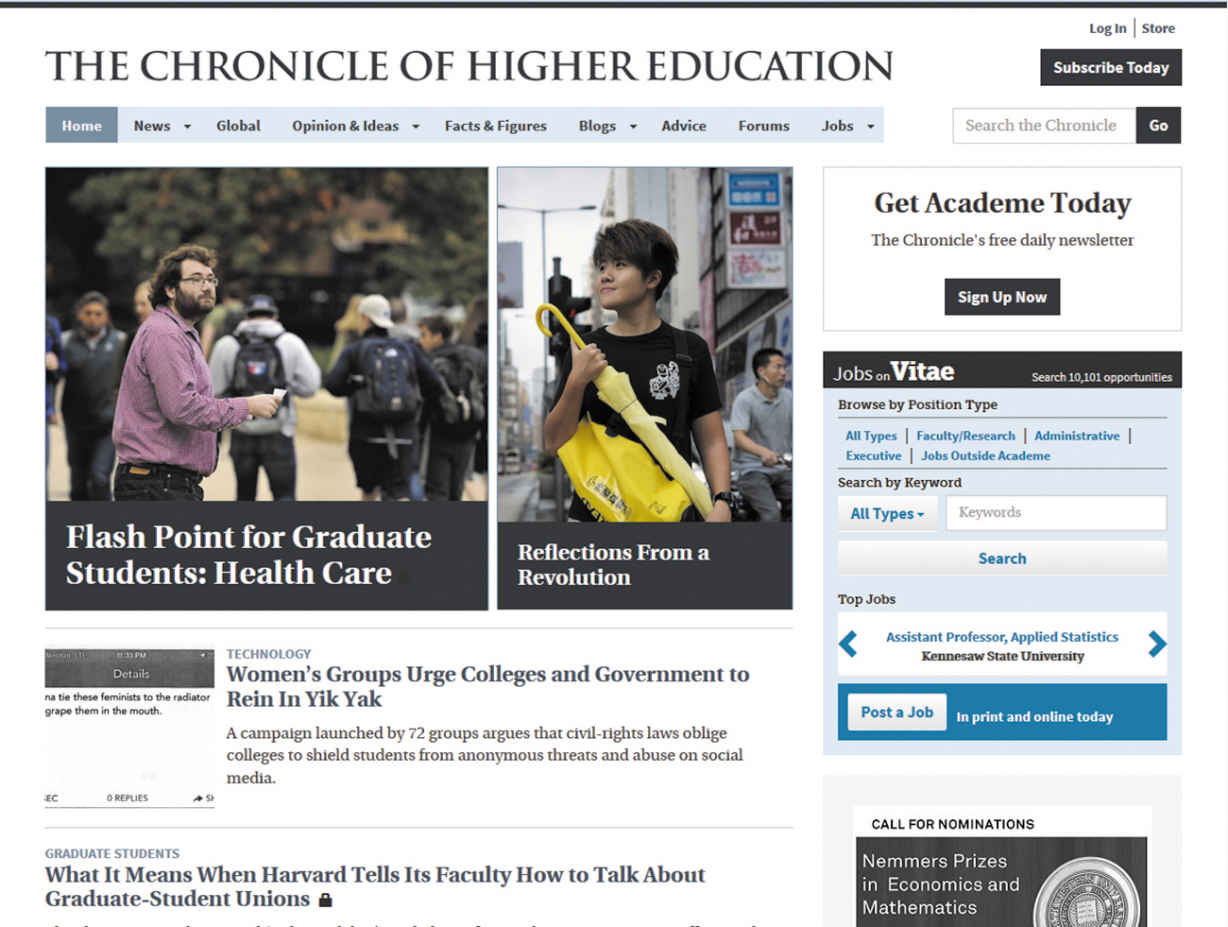

Consider the following two home pages—one from the website for the Chronicle of Higher Education, a publication aimed at college instructors and administrators, and the other from the website for Glamour, a publication aimed at general readers. Assume that on both websites, you have found articles about privacy and social-networking sites. Locate and label the information on each home page that would enable you to determine the suitability of using information from the site in your paper.

Courtesy of The Chronicle of Higher Education, www.chronicle.com; © Nabil K. Mark Photography; © Mark Leong/Redux

Courtesy of Glamour, © Conde Nast; Jason Merritt/Getty Images (Lena Dunham); TC: Wireimage/Getty Images (Jen Aniston); TR: AP/Wire Photo (Kathryn Smith); Bottom: Superstock/Getty Images (phone operator)

EXERCISE 8.4

EXERCISE 8.4

Here are the mission statements —statements of the organizations’ purposes—from the websites for the Chronicle of Higher Education and Glamour, whose home pages you considered in Exercise 8.3. What additional information can you get from these mission statements? How do they help you to evaluate the sites as well as the information that might appear on the sites?

Courtesy of The Chronicle of Higher Education, www.chronicle.com

Cover Photo by: Steven Pan/Glamour; © Conde Nast

EXERCISE 8.5

EXERCISE 8.5

Each of the following sources was found on a website: Jonathan Mahler, “Who Spewed That Abuse? Anonymous Yik Yak App Isn’t Telling,” p. 310; Jennifer Golbeck, “All Eyes on You,” p. 316; Craig Desson, “My Creepy Instagram Map Knows Where I Live,” p. 322; and Sharon Jayson, “Is Online Dating Safe?,” p. 324.

Assume that you are preparing to write an essay on the topic of whether information posted on social-networking sites threatens privacy. First, visit the websites on which the articles appear, and evaluate each site for accuracy, credibility, objectivity, currency, comprehensiveness, and authority. Then, using the same criteria, evaluate each source.

This article originally ran in the New York Times on March 8, 2015.

JONATHAN MAHLER

WHO SPEWED THAT ABUSE? ANONYMOUS YIK YAK APP ISN’T TELLING

During a brief recess in an honors course at Eastern Michigan University last fall, a teaching assistant approached the class’s three female professors. “I think you need to see this,” she said, tapping the icon of a furry yak on her iPhone.1

The app opened, and the assistant began scrolling through the feed. While the professors had been lecturing about post-apocalyptic culture, some of the 230 or so freshmen in the auditorium had been having a separate conversation about them on a social media site called Yik Yak. There were dozens of posts, most demeaning, many using crude, sexually explicit language and imagery.2

After class, one of the professors, Margaret Crouch, sent off a flurry of emails—with screenshots of some of the worst messages attached—to various university officials, urging them to take some sort of action. “I have been defamed, my reputation besmirched. I have been sexually harassed and verbally abused,” she wrote to her union representative. “I am about ready to hire a lawyer.”3

In the end, nothing much came of Ms. Crouch’s efforts, for a simple reason: Yik Yak is anonymous. There was no way for the school to know who was responsible for the posts.4

Eastern Michigan is one of a number of universities whose campuses have been roiled by offensive “yaks.” Since the app was introduced a little more than a year ago, it has been used to issue threats of mass violence on more than a dozen college campuses, including the University of North Carolina, Michigan State University, and Penn State. Racist, homophobic, and misogynist “yaks” have generated controversy at many more, among them Clemson, Emory, Colgate, and the University of Texas. At Kenyon College, a “yakker” proposed a gang rape at the school’s women’s center.5

In much the same way that Facebook swept through the dorm rooms of America’s college students a decade ago, Yik Yak is now taking their smartphones by storm. Its enormous popularity on campuses has made it the most frequently downloaded anonymous social app in Apple’s App Store, easily surpassing competitors like Whisper and Secret. At times, it has been one of the store’s 10 most downloaded apps.6

Like Facebook or Twitter, Yik Yak is a social media network, only without user profiles. It does not sort messages according to friends or followers but by geographic location or, in many cases, by university. Only posts within a 1.5-mile radius appear, making Yik Yak well suited to college campuses. Think of it as a virtual community bulletin board—or maybe a virtual bathroom wall at the student union. It has become the go-to social feed for college students across the country to commiserate about finals, to find a party, or to crack a joke about a rival school.7

Much of the chatter is harmless. Some of it is not.8

“Yik Yak is the Wild West of anonymous social apps,” said Danielle Keats Citron, a law professor at University of Maryland and the author of Hate Crimes in Cyberspace. “It is being increasingly used by young people in a really intimidating and destructive way.”9

“Much of the chatter is harmless. Some of it is not.”

Colleges are largely powerless to deal with the havoc Yik Yak is wreaking. The app’s privacy policy prevents schools from identifying users without a subpoena, court order, or search warrant, or an emergency request from a law-enforcement official with a compelling claim of imminent harm. Schools can block access to Yik Yak on their Wi-Fi networks, but banning a popular social media network is controversial in its own right, arguably tantamount to curtailing freedom of speech. And as a practical matter, it doesn’t work anyway. Students can still use the app on their phones with their cell service.10

Yik Yak was created in late 2013 by Tyler Droll and Brooks Buffington, fraternity brothers who had recently graduated from Furman University in South Carolina. Mr. Droll majored in information technology and Mr. Buffington in accounting. Both 24, they came up with the idea after realizing that there were only a handful of popular Twitter accounts at Furman, almost all belonging to prominent students, like athletes. With Yik Yak, they say, they hoped to create a more democratic social media network, one where users didn’t need a large number of followers or friends to have their posts read widely.11

“We thought, ‘Why can’t we level the playing field and connect everyone?’” said Mr. Droll, who withdrew from medical school a week before classes started to focus on the app.12

“When we made this app, we really made it for the disenfranchised,” Mr. Buffington added.13

Just as Mark Zuckerberg and his roommates introduced Facebook at Harvard, Mr. Buffington and Mr. Droll rolled out their app at their alma mater, relying on fraternity brothers and other friends to get the word out.14

Within a matter of months, Yik Yak was in use at 40 or so colleges in the South. Then came spring break. Some early adopters shared the app with college students from all over the country at gathering places like Daytona Beach and Panama City. “And we just exploded,” Mr. Buffington said.15

Mr. Droll and Mr. Buffington started Yik Yak with a loan from Mr. Droll’s parents. (His parents also came up with the company’s name, which was inspired by the 1958 song, “Yakety Yak.”) In November, Yik Yak closed a $62 million round of financing led by one of Silicon Valley’s biggest venture capital firms, Sequoia Capital, valuing the company at hundreds of millions of dollars.16

The Yik Yak app is free. Like many tech start-ups, the company, based in Atlanta, doesn’t generate any revenue. Attracting advertisers could pose a challenge, given the nature of some of the app’s content. For now, though, Mr. Droll and Mr. Buffington are focused on extending Yik Yak’s reach by expanding overseas and moving beyond the college market, much as Facebook did.17

Yik Yak’s popularity among college students is part of a broader reaction against more traditional social media sites like Facebook, which can encourage public posturing at the expense of honesty and authenticity.18

“Share your thoughts with people around you while keeping your privacy,” Yik Yak’s home page says. It is an attractive concept to a generation of smartphone users who grew up in an era of social media—and are thus inclined to share—but who have also been warned repeatedly about the permanence of their digital footprint.19

In a sense, Yik Yak is a descendant of JuicyCampus, an anonymous online college message board that enjoyed a brief period of popularity several years ago. Matt Ivester, who founded JuicyCampus in 2007 and shut it in 2009 after it became a hotbed of gossip and cruelty, is skeptical of the claim that Yik Yak does much more than allow college students to say whatever they want, publicly and with impunity. “You can pretend that it is serving an important role on college campuses, but you can’t pretend that it’s not upsetting a lot of people and doing a lot of damage,” he said. “When I started JuicyCampus, cyberbullying wasn’t even a word in our vernacular. But these guys should know better.”20

Yik Yak’s founders say the app’s overnight success left them unprepared for some of the problems that have arisen since its introduction. In response to complaints, they have made some changes to their product, for instance, adding filters to prevent full names from being posted. Certain keywords, like “Jewish,” or “bomb,” prompt this message: “Pump the brakes, this yak may contain threatening language. Now it’s probably nothing and you’re probably an awesome person but just know that Yik Yak and law enforcement take threats seriously. So you tell us, is this yak cool to post?”21

In cases involving threats of mass violence, Yik Yak has cooperated with authorities. Most recently, in November, local police traced the source of a yak—“I’m gonna [gun emoji] the school at 12:15 p.m. today”—to a dorm room at Michigan State University. The author, Matthew Mullen, a freshman, was arrested within two hours and pleaded guilty to making a false report or terrorist threat. He was spared jail time but sentenced to two years’ probation and ordered to pay $800 to cover costs connected to the investigation.22

In the absence of a specific, actionable threat, though, Yik Yak zealously protects the identities of its users. The responsibility lies with the app’s various communities to police themselves by “upvoting” or “downvoting” posts. If a yak receives a score of negative 5, it is removed. “Really, what it comes down to is that we try to empower the communities as much as we can,” Mr. Droll said.23

When Yik Yak appeared, it quickly spread across high schools and middle schools, too, where the problems were even more rampant. After a rash of complaints last winter at a number of schools in Chicago, Mr. Droll and Mr. Buffington disabled the app throughout the city. They say they have since built virtual fences—or “geo-fences”—around about 90 percent of the nation’s high schools and middle schools. Unlike barring Yik Yak from a Wi-Fi network, which has proved ineffective in limiting its use, these fences actually make it impossible to open the app on school grounds. Mr. Droll and Mr. Buffington also changed Yik Yak’s age rating in the App Store from 12 and over to 17 and over.24

Toward the end of last school year, almost every student at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire had the app on his or her phone and checked it constantly to read the anonymous attacks on fellow students, faculty members, and deans.25

“Please stop using Yik Yak immediately,” Arthur Cosgrove, the dean of residential life, wrote in an email to the student body. “Remove it from your phones. It is doing us no good.”26

At Exeter’s request, the company built a geo-fence around the school, but it covered only a few buildings. Students continued using the app on different parts of the sprawling campus.27

“We made the app for college kids, but we quickly realized it was getting into the hands of high schoolers, and high schoolers were not mature enough to use it,” Mr. Droll said.28

The widespread abuse of Yik Yak on college campuses, though, suggests that the distinction may be artificial. Last spring, Jordan Seman, then a sophomore at Middlebury College, was scrolling through Yik Yak in the dining hall when she happened across a post comparing her to a “hippo” and making a sexual reference about her. “It’s so easy for anyone in any emotional state to post something, whether that person is drunk or depressed or wants to get revenge on someone,” she said. “And then there are no consequences.”29

In this sense, the problem with Yik Yak is a familiar one. Anyone who has browsed the comments of an Internet post is familiar with the sorts of intolerant, impulsive language that the cover of anonymity tends to invite. But Yik Yak’s particular design can produce especially harmful consequences.30

“It’s a problem with the Internet culture in general, but when you add this hyper-local dimension to it, it takes on a more disturbing dimension,” says Elias Aboujaoude, a Stanford psychiatrist and the author of Virtually You. “You don’t know where the aggression is coming from, but you know it’s very close to you.”31

Jim Goetz, a partner at Sequoia Capital who recently joined Yik Yak’s board, said the app’s history of misuse was a concern when his firm considered investing in the company. But he said he was confident that Mr. Droll and Mr. Buffington were committed to ensuring more positive interactions on Yik Yak, and that over time, the constructive voices would overwhelm the destructive ones.32

“It’s certainly a challenge to the company,” Mr. Goetz said. “It’s not going to go away in a couple of months.”33

Ms. Seman wrote about her experience being harassed on Yik Yak in the school newspaper, the Middlebury Campus, prompting a schoolwide debate over what to do about the app. Unable to reach a consensus, the paper’s editorial board wrote two editorials, one urging a ban, the other arguing that the problem wasn’t Yik Yak but the larger issue of cyberbullying. (Middlebury has not taken any action.)34

Similar debates have played out at other schools. At Clemson, a group of African-American students unsuccessfully lobbied the university to ban Yik Yak when some racially offensive posts appeared after a campus march to protest the grand jury’s decision not to indict a white police officer in the fatal shooting of an unarmed black teenager in Ferguson, Mo. “We think that in the educational community, First Amendment rights are very important,” said Leon Wiles, the school’s chief diversity officer. “It’s just problematic because you have young people who use it with no sense of responsibility.”35

During the fall, Maxwell Zoberman, the sophomore representative to the student government at Emory, started noticing a growing number of yaks singling out various ethnic groups for abuse. “Fave game to play while driving around Emory: not hit an Asian with a truck,” read one.36

“Guys stop with all this hate. Let’s just be thankful we arn’t black,” read another.37

After consulting the university’s code, Mr. Zoberman discovered that statements deemed derogatory to any particular group of people were not protected by the school’s open expression policy, and were in fact in violation of its discriminatory harassment rules. Just because the statements were made on an anonymous social-media site should not, in his mind, prevent Emory from acting to enforce its own policies. “It didn’t seem right that the school took one approach to hate speech in a physical medium and another one in a digital medium,” he said.38

Mr. Zoberman drafted a resolution to have Yik Yak disabled on the school’s Wi-Fi network. He recognized that this would not stop students from using the app, but he nevertheless felt it was important for the school to take a stand.39

After Mr. Zoberman formally proposed his resolution to the student government, someone promptly posted about it on Yik Yak. “The reaction was swift and harsh,” he said. “I seem to have redirected all of the fury of the anonymous forum. Yik Yak was just dominated with hateful and other aggressive posts specifically about me.” One compared him to Hitler.40

A few colleges have taken the almost purely symbolic step of barring Yik Yak from their servers. John Brown University, a Christian college in Arkansas, did so after its Yik Yak feed was overrun with racist commentary during a march connected to the school’s World Awareness Week. Administrators at Utica College in upstate New York blocked the app in December in response to a growing number of sexually graphic posts aimed at the school’s transgender community.41

In December, a group of 50 professors at Colgate University—which had experienced a rash of racist comments on the app earlier in the fall—tried a different approach, flooding the app with positive posts.42

Generally speaking, though, the options are limited. A student who felt that he or she had been the target of an attack on Yik Yak could theoretically pursue defamation charges and subpoena the company to find out who had written the post. But it is a difficult situation to imagine, given the cost and murky legal issues involved. Schools will probably just stand back and hope that respect and civility prevail, that their communities really will learn to police themselves.43

Yik Yak’s founders say their start-up is just experiencing some growing pains. “It’s definitely still a learning process for us,” Mr. Buffington said, “and we’re definitely still learning how to make the community more constructive.”44

“Yik Yak’s founders say their start-up is just experiencing some growing pains.”

Golbeck’s essay appeared in the September/October 2014 issue of Psychology Today.

JENNIFER GOLBECK

ALL EYES ON YOU

Every day, nearly everywhere I go, I’m being followed. That’s not paranoia. It’s a fact. Consider:1

On my local Washington, D.C., streets, I am constantly watched. The city government alone has hundreds of traffic and surveillance cameras. And then there are the cameras in parks, office buildings, ATM lobbies, and, of course, around every federal building and landmark. On an average day, my image is captured by well over 100 cameras.2

When I’m online and using social media, a wealth of information about my interests and routines is collected behind the scenes. I employ an add-on on my browser that blocks companies from tracking my searches and visits. In just one recent month, it reported blocking nearly 16,000 separate attempts to access my data online.3

I’m monitored offline, too. Anytime I use a reward card at a supermarket, department store, or other retail outlet, my purchase is recorded, and the data either sold to other marketers or used to predict my future purchases and guide me to make them in that store. Department store tracking based on purchase records can even conclude that a woman is pregnant and roughly when she is due.4

My own devices report on me. I carry an iPhone, which tracks and records my every movement. This will help me find my phone if I ever lose it (I haven’t yet), but it also provides Apple with a treasure trove of data about my daily habits.5

Data on any call I place or email I send may be collected by the National Security Agency. Recent news reports have revealed that the federal intelligence arm may be collecting metadata on phone and Internet traffic—when Americans communicate and with whom, if not the actual content of those communications. As Barton Gellman, Pulitzer Prize-winning intelligence reporter for the Washington Post, said during a recent panel discussion, it’s not that the NSA knows everything about everyone, but that “it wants to be able to know anything about anybody.”6

Thirty years after 1984, Big Brother is here. He’s everywhere. In many cases, we’ve invited him in. So the question we have to ask now is, How does this constant surveillance affect us and what, if anything, can we do about it?7

“Get Over It.”

There’s no question our privacy has been eroded with the help of technology. There’s also little question that those most responsible aren’t much inclined to retreat. As Scott McNealy, cofounder of Sun Microsystems, famously said: “You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.”8

Privacy is an intangible asset. If we never think about it, we may not realize it’s gone. Does it still matter? Elias Aboujaoude, a professor of psychiatry at Stanford University and the author of Virtually You: The Dangerous Powers of the E-Personality, insists that it does. “We cannot afford to just ‘get over it,’ for nothing short of our self-custody seems to be at stake,” he says. “At its heart, this is about our psychological autonomy and the maintenance of some semblance of control over the various little details that make us us.”9

“Does it still matter?”

In the modern surveillance environment, with so much personal information accessible by others—especially those with whom we have not chosen to share that information—our sense of self is threatened, as is our ability to manage the impression others have of us, says Ian Brown, senior research fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute.10

If people treat us differently based on what they have discovered online, if the volume of data available about us eradicates our ability to make a first impression on a date or a job interview, the result, Brown believes, is reduced trust, increased conformity, and even diminished civic participation. The impact can be especially powerful when we know that our information was collected and shared without our consent.11

To be sure, we are responsible for much of this. We’re active participants in creating our surveillance record. Along with all of the personal information we voluntarily, often eagerly, share on social networks and shopping sites—and few of us take advantage of software or strategies to limit our digital footprint—we collectively upload 144,000 hours of video footage a day to YouTube. And with tech enthusiasts trumpeting personal drones as the next hot item, we may soon be equipped to photograph ourselves and, just as easily, our neighbors, from above.12

Most of us try to curate the public identities we broadcast—not only through the way we dress and speak in public, but also in how we portray ourselves on social-media platforms. The problem arises when we become conscious that uninvited observers are also tuning in. “The most fundamental impact surveillance has on identity,” Brown says, “is that it reduces individuals’ control over the information they disclose about their attributes in different social contexts, often to such powerful actors as the state or multinational corporations.” When we discover that such entities—and third parties to which our information may be sold or shared—make decisions about us based on that data, our sense of self can be altered.13

The Right to Be Forgotten

There are existential threats to our psyches in a world where nothing we do can be forgotten, believes Viktor Mayer-Schönberger, professor of Internet governance and regulation at the Oxford Internet Institute. His book, Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital Age, relates the experiences of people whose lives were negatively affected because of information available about them online.14

In 2006, for example, psychotherapist Andrew Feldmar drove from his Vancouver home to pick up a friend flying in to Seattle. At the United States border, which Feldmar had crossed scores of times, a guard decided to do an Internet search on him. The query returned an article Feldmar had written for an academic journal five years earlier, in which he revealed that he’d taken LSD in the 1960s. The guard held Feldmar for four hours, fingerprinted him, and asked him to sign a statement that he had taken drugs almost 40 years earlier. He was barred from entry into the U.S.15

Aboujaoude relates the story of “Rob,” a nurse in a public hospital emergency room chronically short on staff. His willingness to fill in when the ER needed extra hands led to significant overtime pay. When a website published an “exposé” of seemingly overpaid public employees, Rob’s name and salary were posted as an example. He was then hounded by hate mail—both paper and electronic. People called his house, and his daughter was harassed at school. Eventually the stress and constant criticism made him feel as if he were becoming paranoid and led him to Aboujaoude as a therapy patient.16

The ability to forget past events, Mayer-Schönberger says, or at least to let them recede in our minds, is critical for decision making. Psychologists often note that our ability to forget is a valuable safety valve. As we naturally forget things over time, we can move on and make future choices without difficult or embarrassing episodes clouding our outlook. But when our decisions are tangled up in the perfect memory of the Internet—when we must factor in the effect of our online footprint before every new step—“we may lose a fundamental human capacity: to live and act firmly in the present,” he says.17

The result can be demoralizing and even paranoia-inducing. Lacking the power to control what, when, and with whom we share, Mayer-Schönberger explains, our sense of self may be diminished, leading to self-doubt internally and self-censorship externally, as we begin to fixate on what others will think about every potentially public action and thought, now and in the future.18

Under normal circumstances, the passage of time allows us to shape our narrative, cutting out or minimizing less important (or more embarrassing) details to form a more positive impression. When we can’t put the past behind us, it can affect our behavior and intrude on our judgment. Instead of making decisions fully in the present, we make them while weighed down by every detail of our past.19

The effects are not trivial. A range of people, from a long-reformed criminal seeking a fresh slate to a sober former college party girl in the job market, can find that the omnipresence of public records and posted photos permanently holds them back. At its worst, these weights can inhibit one’s desire to change. If we can never erase the record of one mistake we made long ago, if we’re convinced it will only continue to hinder our progress, what motivation do we have to become anyone different from the person who made that mistake? For that matter, why bother moving beyond conflicts with others if the sources of those disputes remain current online? With easily accessible digital reminders, bygones cannot be bygones. It’s no accident that the most successful legal campaign yet against permanent digital records hinges on “the right to be forgotten.”20

“With easily accessible digital reminders, bygones cannot be bygones.”

A Spanish lawyer, Mario Costeja González, sued Google over search results that prominently returned a long-ago news article detailing a government order that he sell his home to cover unpaid debts. The European Court of Justice ruled in his favor, asserting, based on an older legal concept allowing ex-convicts to object to the publication of information related to their crimes, that each of us has the right to be forgotten. Even if the information about the man’s foreclosure is true, the court ruled, it is “irrelevant, or no longer relevant,” and should be blocked from Google’s (and other browsers’) searches.21

Google is now working to implement a means for European users to request that certain information be removed from their searches, a process it is finding to be more complicated than many observers had imagined. No similar verdict has been handed down in the U.S., and privacy experts believe that Congress is unlikely to take up the issue anytime soon.22

Do Cameras Make Us More Honorable, or Just Paranoid?

Trust is perennially strained in our workplaces, where more employees than ever are being overseen via cameras, recorded phone calls, location tracking, and email monitoring. Studies dating back two decades have consistently found that employees who were aware that they were being surveilled found their working conditions more stressful and reported higher levels of anxiety, anger, and depression. More recent research indicates that, whatever productivity benefits management hopes to realize, increased surveillance on the office floor leads to poorer performance, tied to a feeling of loss of control as well as to lower job satisfaction.23

Outside the workplace, we expect more freedom and wider opportunity to defend our privacy. But even as we become more savvy about online tracking, we’re beginning to realize just how little we can do about so-called “passive” surveillance—the cameras recording our movements as we go about our business—especially because so much of this observation is covert. The visual range of surveillance cameras has expanded even as their physical size has shrunk, and as satellites and drones become more accurate from increasing distances, social scientists have begun to explore how near-constant surveillance, at least in the public sphere, affects our behavior. The research so far identifies both concerns and potential benefits. We tend, for example, to be more cooperative and generous when we suspect someone is watching—a recent Dutch study found that people were more likely to intervene when witnessing a (staged) crime if they knew they were being watched, either by others or by a camera. But we don’t become more generous of spirit. Pierrick Bourrat, a graduate student at the University of Sydney, and cognitive scientist Nicolas Baumard of the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, recently published a study on how we judge other people’s bad behavior. They found that when subjects believed they were being watched, they rated others’ actions more severely. A possible explanation: When we think we’re being observed, we adjust our behavior to project an image of moral uprightness through harsher-than-usual judgment of others.24

But adjusting our behavior in the presence of cameras to project an image aligned with presumed social norms can have a downside. The Oxford Internet Institute’s Brown sees a cooling effect on public discourse, because when people think they’re being watched, they may behave, consciously or not, in ways that comply with what they presume governmental or other observers want. That doesn’t mean we trust the watchers. A recent Gallup poll found that only 12 percent of Americans have “a lot of trust” that the government will keep their personal information secure; we trust banks three times as much.25

When Users Strike Back

What would happen if we really tried to root out all of the surveillance in our life and took action to erase ourselves from it? We think such knowledge would equal power, but it may just bring on paranoia. Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist Julia Angwin tried for a year to prevent her life from being monitored. She used a disposable cell phone. She installed encryption software on her email accounts. She even developed a fake identity (“Ida Tarbell”) to prevent her online and commercial activities from being tied to her true self.26

Angwin detailed these efforts in her book, Dragnet Nation, which, while ultimately hopeful, relates a draining journey during which she lost trust in nearly every institution that holds her data. Even with her resources and single-mindedness, Angwin could achieve only partial success: Her past personal data, after all, were stored in bits and pieces by hundreds of brokers that traffic in information, and she had no means of turning back the clock.27

The efforts also affected her worldview: “I wasn’t happy with the toll that my countersurveillance techniques had taken on my psyche. The more I learned about who was watching me, the more paranoid I became. By the end of my experiment, I was refusing to have digital conversations with my close friends without encryption. I began using my fake name for increasingly trivial transactions; a friend was shocked when we took a yoga class together and I casually registered as Ida Tarbell.”28

The Next Level

Modern surveillance does have some clear benefits. Cameras in public spaces help the authorities detect crime and catch perpetrators, though they catch us in the dragnet as well. Cell phone tracking and networked late-model cars allow us to be found if we become lost or injured, and mapping apps are incredibly useful for directing us where we want to go. These features save lives—but all of them constantly transmit our location and generate a precisely detailed record of our movements. Our social media history helps providers put the people and content we prefer front and center when we log on, and our online searches and purchase records allow marketers to offer us discounts at the places we shop most, all the while collecting data on our personal preferences and quirks. Given the difficulty of completely avoiding the monitoring, it may be somewhat reassuring to acknowledge this tradeoff.29

Laura Brandimarte of Carnegie Mellon University and her colleagues have studied people’s willingness to disclose personal information. They found that when entities give people more control over the publication of their information, people disclose more about themselves—even if it is also clear that the information will be accessed and seen by others more often than it currently is.30

Their work demonstrates the concept of illusion of control. In many situations, we tend to overestimate the control we have over events, especially when we get cues that our actions matter. The risk to our private information comes not just from what we’ve shared but from how much of it is sold or made available to others. And yet when we feel that we have been given more control over our information’s dissemination, our privacy concerns decrease and our disclosure increases, even though that apparent control does not actually diminish the possibility that our data will be shared. “The control people perceive over the publication of personal information makes them pay less attention to the lack of control they have over access by others,” Brandimarte says.31

In other words, we are simply not very sophisticated when it comes to making choices about what to share.32

When it comes to privacy-protection, the first issue for social-media users to grapple with is inertia: According to a range of surveys of U.S. Facebook users, for example, as many as 25 percent have never checked or adjusted their privacy settings to impose even the most basic restriction on their postings: not making them public.33

There is a growing availability of privacy fixes for homes, cell phones, and computers. Whether they will be able to keep up with tracking mechanisms is unclear. But evidence suggests that even if they work as advertised, we may not be savvy enough to use them.34

So we have limited options to protect our privacy, and few of us take advantage even of those. What’s the ultimate cost? Aboujaoude argues that our need for privacy and true autonomy is rooted in the concept of individuation, the process by which we develop and maintain an independent identity. It’s a crucial journey that begins in childhood, as we learn to separate our own identity from that of our parents, and continues through adulthood.35

Many psychologists emphasize that maintaining self-identity requires a separation from others, and Aboujaoude believes that, in today’s environment, control over personal information is a critical piece of the process. “You are a psychologically autonomous individual,” he says, “if you have the option to keep your person to yourself and dole out the pieces as you see fit.”36

And who do we become if we don’t have that option? We may soon find out.37

I Married a P.I.

When we worry about who might be watching us, we tend to focus our concern on Facebook, the NSA, or marketers. But we may want to consider our own partners as well.38

Sue Simring, an associate professor at Columbia University’s School of Social Work and a psychotherapist with four decades of experience working primarily with couples, says the ease with which people can now monitor each other has radically changed her work. “It used to be that, unless you literally discovered them [in flagrante], there was no way to know for sure that people were having an affair,” she says.39

No more.40

When spouses stray today, their digital trail inevitably provides clues for the amateur sleuth with whom they share a bed. Simring describes one case in which a man had carried on an affair for years while traveling for work. He managed to keep it secret until a technical glitch started sending copies of his text messages to his wife’s iPad.41

But the easy availability of tools to track a partner can cut both ways. In the case of another couple that Simring worked with, the husband was convinced that his wife was having an affair. Determined to catch her, he undertook increasingly complex and invasive surveillance efforts, eventually monitoring all of her communications and installing spy cameras in their home to catch her in the act. The more he surveilled, the more his paranoia grew. It turned out that the wife was not having an affair, but because of the trauma the husband’s surveillance caused her, she ended the marriage.42

This essay was posted to the online newspaper The Start on February 27, 2015.

CRAIG DESSON

MY CREEPY INSTAGRAM MAP KNOWS WHERE I LIVE

U.S. Congressman Aaron Schock’s reputation took a hit this week when the Associated Press used geo-location data from his Instagram account to show how he was flying on private jets provided by campaign donors, expensed massages, and bought Katy Perry tickets for his interns.1

The reporters involved explained that “the AP extracted location data associated with each image, then correlated it with flight records showing airport stopovers and expenses later billed for air travel against Schock’s office and campaign records.”2

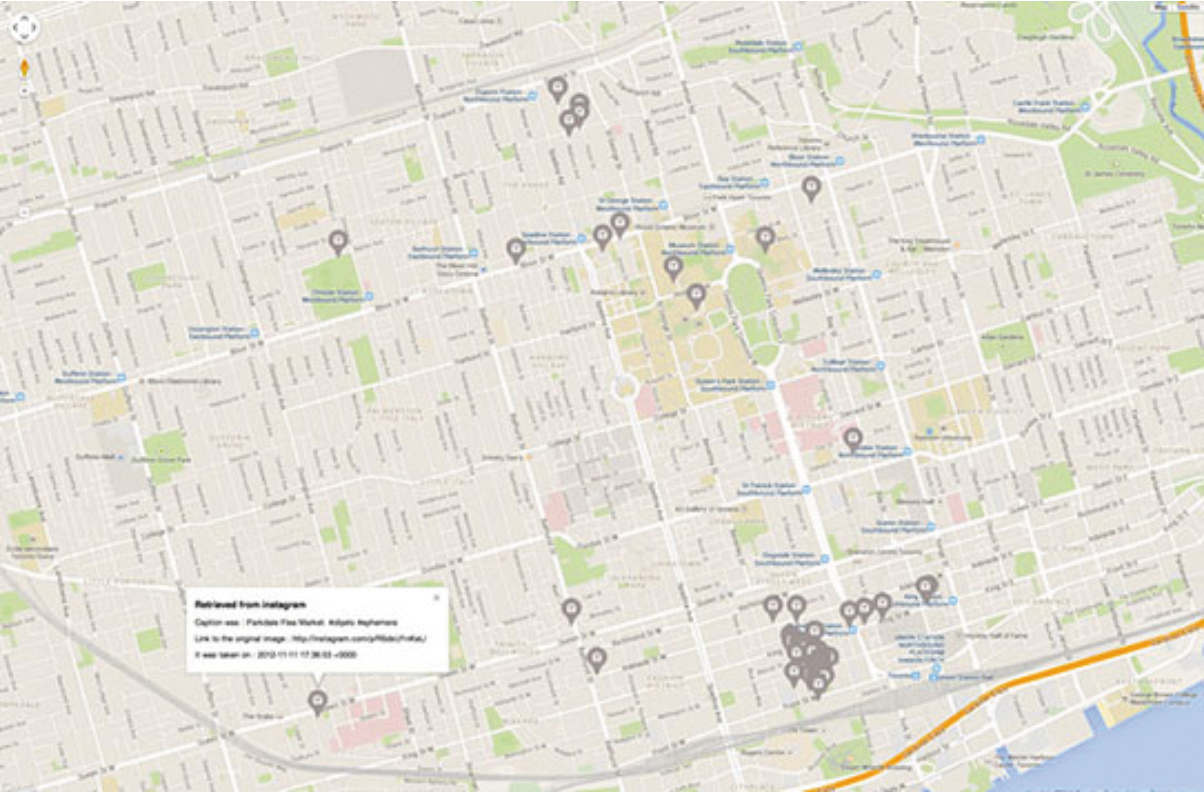

To track somebody on Instagram the way AP did for the Schock story isn’t difficult. There is a program called Creepy that will create a Google map showing where you’ve been, based on what you’ve shared on Instagram, Twitter, and Flickr.3

I ran Creepy on my own Instagram account and found it wouldn’t be hard for a stranger to figure out where I live in the Annex.4

This is the map the program made about my account, and with a bit of deductive logic it’s clear I live just north of Bloor and Spadina.5

The photos taken around Front St. are all interiors of offices, because that’s where I’ve worked for the past two and a half years. The photos taken along major streets such as King and Bloor portray me hanging out with friends.6

Then there is the funny collection of dots north of Bloor in the Annex that link to Instagram photos of an apartment’s interior.7

You don’t need to be Sherlock Holmes to guess that’s my home.8

It’s true that 20 years ago, a phonebook might have led a stranger to my home address. But I would at least know that I had a listed number. The trouble with Instagram tracking is that most users have no idea their photo-sharing app is also building a detailed history of where they work and live.9

If Aaron Schock, a congressman with paid communications people, couldn’t figure this out, then it’s likely most members of the public have no idea this is going on.10

USA Today posted this article to its website on March 27, 2014.

SHARON JAYSON

IS ONLINE DATING SAFE?

Change may be coming to the rapidly growing dating industry as concern mounts about the privacy and safety of all online and mobile users.1

Sen. Al Franken, D-Minn., introduced legislation Thursday requiring companies to get customers’ permission before collecting location data off their mobile devices and sharing it with others.2

It’s a move that would greatly affect dating websites and apps. As mobile dating proliferates, the focus no longer is just on daters leery of scams or sexual predators, but on keeping their locations confidential.3

“As mobile dating proliferates, the focus no longer is just on daters leery of scams or sexual predators, but on keeping their locations confidential.”

“This stuff is advancing at a faster and faster rate, and we’ve got to try and catch up,” Franken says. “This is about Americans’ right to privacy and one of the most private things is your location.”4

Illinois, New York, New Jersey, and Texas have laws that require Internet dating sites to disclose whether they conduct criminal background checks on users and to offer advice on keeping safe.5

“I see more regulation about companies stating what kind of information they actually use and more about their specific operation(s),” says analyst Jeremy Edwards, who authored a report on the industry last fall for IBISWorld, a Santa Monica, Calif.-based market research company. “I expect them to have to be more explicit in what they do with their data and what they require of users.”6

According to a Pew Research Center report in October, 11% of American adults—and 38% of those currently “single and looking” for a partner—say they’ve used online dating sites or mobile dating apps.7

“We entrust some incredibly sensitive information to online dating sites,” says Rainey Reitman of the San Francisco, Calif.-ased Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for user privacy amid technology development. “People don’t realize how much information they’re exposing even by doing something as slight as uploading a photograph.”8

He adds, “Many online apps are very cavalier about collecting that information and perhaps exposing it in a way that would make you uncomfortable.”9

Dating services eHarmony, Match.com, and Spark Networks and ChristianMingle signed an agreement in 2012 with the California attorney general’s office to protect customers with online safety tools. These include companies checking subscribers against national sex offender registries and providing a rapid abuse reporting system for members.10

However, cyberdating expert Julie Spira of Los Angeles says such reports are sometimes little more than revenge.11

“When people get reported, sometimes it’s because they got jilted,” she says. “How do you quantify when someone feels rejected and pushes the report button, and when somebody really feels scared?”12

Match.com, which has 1.9 million paid subscribers, has been screening all subscribers against sexual offender registries since the summer of 2011, according to spokesman Matthew Traub. Earlier that year, a woman sued the dating site saying she was assaulted by someone she met through it.13

Edwards believes dating sites are doing what they can to help users be safe.14

“It’s difficult for these companies to do much else than provide information and tips,” he says. “Meeting someone through one of these websites does not present any greater risk than meeting someone in a bar or any other setting. There’s no real added risk because you don’t know who anyone is when you meet them for the first time.”15

EXERCISE 8.6

EXERCISE 8.6

Read the blog post below and then answer the questions on page 327.

This article first appeared on Mashable.com on February 6, 2012.

SAM LAIRD

SHOULD ATHLETES HAVE SOCIAL MEDIA PRIVACY? ONE BILL SAYS YES

Should universities be allowed to force student athletes to have their Facebook and Twitter accounts monitored by coaches and administrators?1

No, says a bill recently introduced into the Maryland state legislature.2

The bill would prohibit institutions “from requiring a student or an applicant for admission to provide access to a personal account or service through an electronic communications device”—by sharing usernames, passwords, or unblocking private accounts, for example.3

Introduced on Thursday, Maryland’s Senate Bill 434 would apply to all students but particularly impact college sports. Student-athletes’ social media accounts are frequently monitored by authority figures for instances of indecency or impropriety, especially in high-profile sports like football and men’s basketball.4

“Student-athletes’ social media accounts are frequently monitored….”

In one example, a top football recruit reportedly put his scholarship hopes in jeopardy last month after a series of inappropriate tweets.5

The bill’s authors say that it is one of the first in the country to take on the issue of student privacy in the social media age, according to the New York Times.6

Bradley Shear is a Maryland lawyer whose work frequently involves sports and social media. In a recent post to his blog, Shear explained his support for Senate Bill 434 and a similar piece of legislation that would further extend students’ right to privacy on social media.7

“Schools that require their students to turn over their social media user names and/or content are acting as though they are based in China and not in the United States,” Shear wrote.8

But legally increasing student-athletes’ option to social media privacy could also help shield the schools themselves from potential lawsuits.9