Recognizing Logical Fallacies

When you write arguments in college, you follow certain rules that ensure fairness. Not everyone who writes arguments is fair or thorough, however. Sometimes you will encounter arguments in which writers attack the opposition’s intelligence or patriotism and base their arguments on questionable (or even false) assumptions. As convincing as these arguments can sometimes seem, they are not valid because they contain fallacies —errors in reasoning that undermine the logic of an argument. Familiarizing yourself with the most common logical fallacies can help you to evaluate the arguments of others and to construct better, more effective arguments of your own.

The following pages define and illustrate some logical fallacies that you should learn to recognize and avoid.

Begging the Question

The fallacy of begging the question assumes that a statement is self-evident (or true) when it actually requires proof. A conclusion based on such assumptions cannot be valid. For example, someone who is very religious could structure an argument the following way:

| MAJOR PREMISE | Everything in the Bible is true. |

| MINOR PREMISE | The Bible says that Noah built an ark. |

| CONCLUSION | Therefore, Noah’s Ark really existed. |

A person can accept the conclusion of this syllogism only if he or she also accepts the major premise, which has not been proven true. Some people might find this line of reasoning convincing, but others would not—even if they were religious.

Begging the question occurs any time someone presents a debatable statement as if it were true. For example, look at the following statement:

You have unfairly limited my right of free speech by refusing to print my editorial in the college newspaper.

This statement begs the question because it assumes what it should be proving—that refusing to print an editorial violates a person’s right to free speech.

Circular Reasoning

Closely related to begging the question, circular reasoning occurs when someone supports a statement by restating it in different terms. Consider the following statement:

Stealing is wrong because it is illegal.

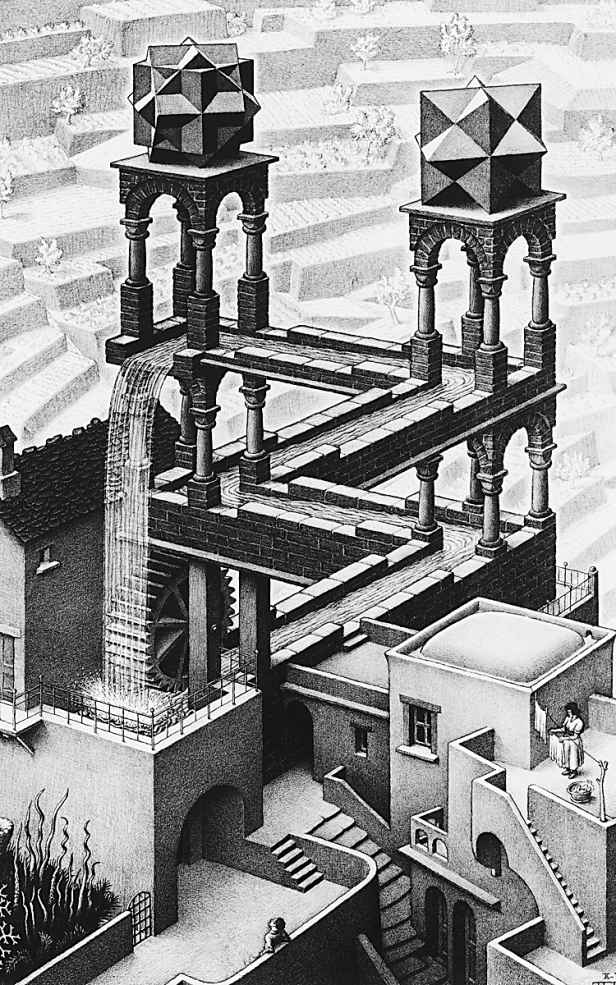

Waterfall, by M. C. Escher. The artwork creates the illusion of water flowing uphill and in a circle. Circular reasoning occurs when the conclusion of an argument is the same as one of the premises.

M. C. Escher’s “Waterfall” © 2012 The M. C. Escher Company-Holland. All rights reserved. www.mcescher.com.

The conclusion of the statement on the previous page is essentially the same as its beginning: stealing (which is illegal) is against the law. In other words, the argument goes in a circle.

Here are some other examples of circular reasoning:

Lincoln was a great president because he is the best president we ever had.

I am for equal rights for women because I am a feminist.

Illegal immigrants should be deported because they are breaking the law.

All of the statements above have one thing in common: they attempt to support a statement by simply repeating the statement in different words.

Weak Analogy

An analogy is a comparison between two items (or concepts)—one familiar and one unfamiliar. When you make an analogy, you explain the unfamiliar item by comparing it to the familiar item.

Although analogies can be effective in arguments, they have limitations. For example, a senator who opposed a government bailout of the financial industry in 2008 made the following argument:

This bailout is doomed from the start. It’s like pouring milk into a leaking bucket. As long as you keep pouring milk, the bucket stays full. But when you stop, the milk runs out the hole in the bottom of the bucket. What we’re doing is throwing money into a big bucket and not fixing the hole. We have to find the underlying problems that have caused this part of our economy to get in trouble and pass legislation to solve them.

The problem with using analogies such as this one is that analogies are never perfect. There is always a difference between the two things being compared. The larger this difference, the weaker the analogy—and the weaker the argument that it supports. For example, someone could point out to the senator that the financial industry—and by extension, the whole economy—is much more complex and multifaceted than a leaking bucket. To analyze the economy, the senator would have to expand his discussion beyond this single analogy (which cannot carry the weight of the entire argument) as well as supply the evidence to support his contention that the bailout was a mistake from the start.

Ad Hominem Fallacy (Personal Attack)

The ad hominem Fallacy occurs when someone attacks the character or the motives of a person instead of focusing on the issues. This line of reasoning is illogical because it focuses attention on the person making the argument, sidestepping the argument itself.

Consider the following statement:

Dr. Thomson, I’m not sure why we should believe anything you have to say about this community health center. Last year, you left your husband for another man.

The above attack on Dr. Thomson’s character is irrelevant; it has nothing to do with her ideas about the community health center. Sometimes, however, a person’s character may have a direct relation to the issue. For example, if Dr. Thomson had invested in a company that supplied medical equipment to the health center, this fact would have been relevant to the issue at hand.

The ad hominem fallacy also occurs when you attempt to undermine an argument by associating it with individuals who are easily attacked. For example, consider this statement:

I think your plan to provide universal heath care is interesting. I’m sure Marx and Lenin would agree with you.

Instead of focusing on the specific provisions of the health-care plan, the opposition unfairly associates it with the ideas of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, two well-known Communists.

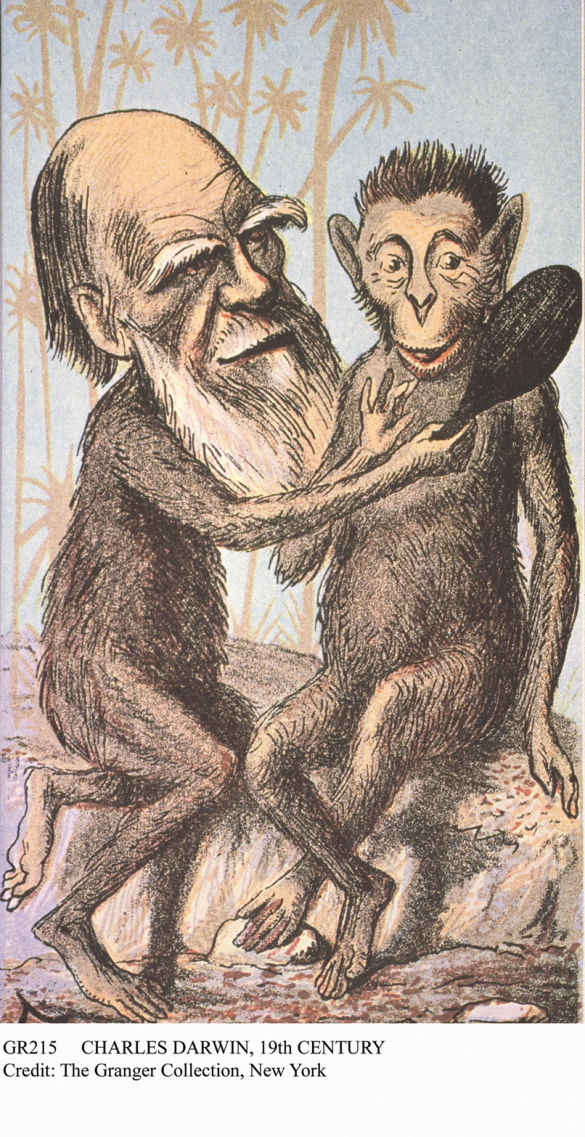

Ad hominem attack against Charles Darwin, originator of the theory of evolution by natural selection

The Granger Collection

Creating a Straw Man

This fallacy most likely got its name from the use of straw dummies in military and boxing training. When writers create a straw man, they present a weak argument that can easily be refuted. Instead of attacking the real issue, they focus on a weaker issue and give the impression that they have effectively refuted an opponent’s argument. Frequently, the straw man is an extreme or oversimplified version of the opponent’s actual position. For example, during a debate about raising the minimum wage, a senator made the following comment:

Those who oppose raising the minimum wage are heartless. They obviously don’t care if children starve.

© SOTK2011/Alamy

Instead of focusing on the minimum wage, the senator misrepresents the opposing position so that it appears cruel. As this example shows, the straw man fallacy is dishonest because it intentionally distorts an opponent’s position to mislead readers.

Hasty or Sweeping Generalization (Jumping to a Conclusion)

A hasty or sweeping generalization (also called jumping to a conclusion) occurs when someone reaches a conclusion that is based on too little evidence. Many people commit this fallacy without realizing it. For example, when Richard Nixon was elected president in 1972, film critic Pauline Kael is supposed to have remarked, “How can that be? No one I know voted for Nixon!” The general idea behind this statement is that if Kael’s acquaintances didn’t vote for Nixon, then neither did most other people. This assumption is flawed because it is based on a small sample.

Sometimes people make hasty generalizations because they strongly favor one point of view over another. At other times, a hasty generalization is simply the result of sloppy thinking. For example, it is easier for a student to simply say that an instructor is an unusually hard grader than to survey the instructor’s classes to see if this conclusion is warranted (or to consider other reasons for his or her poor performance in a course).

Either/Or Fallacy (False Dilemma)

The either/or fallacy (also called a false dilemma) occurs when a person says that there are just two choices when there are actually more. In many cases, the person committing this fallacy tries to force a conclusion by presenting just two choices, one of which is clearly more desirable than the other. (Parents do this with young children all the time: “Eat your carrots, or go to bed.”)

Politicians frequently engage in this fallacy. For example, according to some politicians, you are either pro-life or pro-choice, pro-gun control or anti-gun control, pro-stem-cell research or anti-stem-cell research. Many people, however, are actually somewhere in the middle, taking a much more nuanced approach to complicated issues.

Consider the following statement:

I can’t believe you voted against the bill to build a wall along the southern border of the United States. Either you’re for protecting our border, or you’re against it.

This statement is an example of the either/or fallacy. The person who voted against the bill might be against the wall but not against all immigration restrictions. The person might favor loose restrictions for some people (for example, migrant workers) and strong restrictions for others (for example, drug smugglers). By limiting the options to just two, the speaker oversimplifies the situation and attempts to force the listener to accept a fallacious argument.

The either/or fallacy occurs when a writer presents just two choices when there are actually more.

© Ferhat/Shutterstock.com

Equivocation

The fallacy of equivocation occurs when a key term has one meaning in one part of an argument and another meaning in another part. (When a term is used unequivocally, it has the same meaning throughout the argument.) Consider the following old joke:

The sign said, “Fine for parking here,” so because it was fine, I parked there.

Obviously, the word fine has two different meanings in this sentence. The first time it is used, it means “money paid as a penalty.” The second time, it means “good” or “satisfactory.”

Most words have more than one meaning, so it is important not to confuse the various meanings. For an argument to work, a key term has to have the same meaning every time it appears in the argument. If the meaning shifts during the course of the argument, then the argument cannot be sound.

Consider the following statement:

This is supposed to be a free country, but nothing worth having is ever free.

In this statement, the meaning of a key term shifts. The first time the word free is used, it means “not under the control of another.” The second time, it means “without charge.”

Red Herring

This fallacy gets its name from the practice of dragging a smoked fish across the trail of a fox to mask its scent during a fox hunt. As a result, the hounds lose the scent and are thrown off the track. The red herring fallacy occurs when a person raises an irrelevant side issue to divert attention from the real issue. Used skillfully, this fallacy can distract an audience and change the focus of an argument.

Political campaigns are good sources of examples of the red herring fallacy. Consider this example from the 2016 presidential race:

I know that Donald Trump says that he is for the “little guy,” but he lives in a three-story penthouse in the middle of Manhattan. How can we believe that his policies will help the average American?

The focus of his argument should have been on Trump’s policies, not on the fact that he lives in a penthouse.

Here is another red herring fallacy from the 2016 political campaign:

Hillary Clinton wants us to vote for her, but she will be sixty-nine when she becomes president. I think that this is a problem.

Again, the focus of these remarks should have been on Clinton’s qualifications, not on her age.

Slippery Slope

The slippery-slope fallacy occurs when a person argues that one thing will inevitably result from another. (Other names for the slippery-slope fallacy are the foot-in-the-door fallacy and the floodgates fallacy.) Both these names suggest that once you permit certain acts, you inevitably permit additional acts that eventually lead to disastrous consequences. Typically, the slippery-slope fallacy presents a series of increasingly unacceptable events that lead to an inevitable, unpleasant conclusion. (Usually, there is no evidence that such a sequence will actually occur.)

We encounter examples of the slippery-slope fallacy almost daily. During a debate on same-sex marriage, for example, an opponent advanced this line of reasoning:

If we allow gay marriage, then there is nothing to stop polygamy. And once we allow this, where will it stop? Will we have to legalize incest—or even bestiality?

Whether or not you support same-sex marriage, you should recognize the fallacy of this slippery-slope reasoning. By the last sentence of the passage above, the assertions have become so outrageous that they approach parody. People can certainly debate this issue, but not in such a dishonest and highly emotional way.

You Also (Tu Quoque)

The you also fallacy asserts that a statement is false because it is inconsistent with what the speaker has said or done. In other words, a person is attacked for doing what he or she is arguing against. Parents often encounter this fallacy when they argue with their teenage children. By introducing an irrelevant point—“You did it too”—the children attempt to distract parents and put them on the defensive:

How can you tell me not to smoke when you used to smoke?

Don’t yell at me for drinking. I bet you had a few beers before you were twenty-one.

Why do I have to be home by midnight? Didn’t you stay out late when you were my age?

Arguments such as these are irrelevant. People fail to follow their own advice, but that does not mean that their points have no merit. (Of course, not following their own advice does undermine their credibility.)

Beware the slippery-slope fallacy

© Lon C. Diehl/Photoedit, Inc.

Appeal to Doubtful Authority

Writers of research papers frequently use the ideas of recognized authorities to strengthen their arguments. However, the sources offered as evidence need to be both respected and credible. The appeal to doubtful authority occurs when people use the ideas of nonexperts to support their arguments.

Not everyone who speaks as an expert is actually an authority on a particular issue. For example, when movie stars or recording artists give their opinions about politics, climate change, or foreign affairs—things they may know little about—they are not speaking as experts; therefore, they have no authority. (They are experts, however, when they discuss the film or music industries.) A similar situation occurs with the pundits who appear on television news shows. Some of these individuals have solid credentials in the fields they discuss, but others offer opinions even though they know little about the subjects. Unfortunately, many viewers accept the pronouncements of these “experts” uncritically and think it is acceptable to cite them to support their own arguments.

How do you determine whether a person you read about or hear is really an authority? First, make sure that the person actually has expertise in the field he or she is discussing. You can do this by checking his or her credentials on the Internet. Second, make sure that the person is not biased. No one is entirely free from bias, but the bias should not be so extreme that it undermines the person’s authority. Finally, make sure that you can confirm what the so-called expert says or writes. Check one or two pieces of information in other sources, such as a basic reference text or encyclopedia. Determine if others—especially recognized experts in the field—confirm this information. If there are major points of discrepancy, dig further to make sure you are dealing with a legitimate authority.

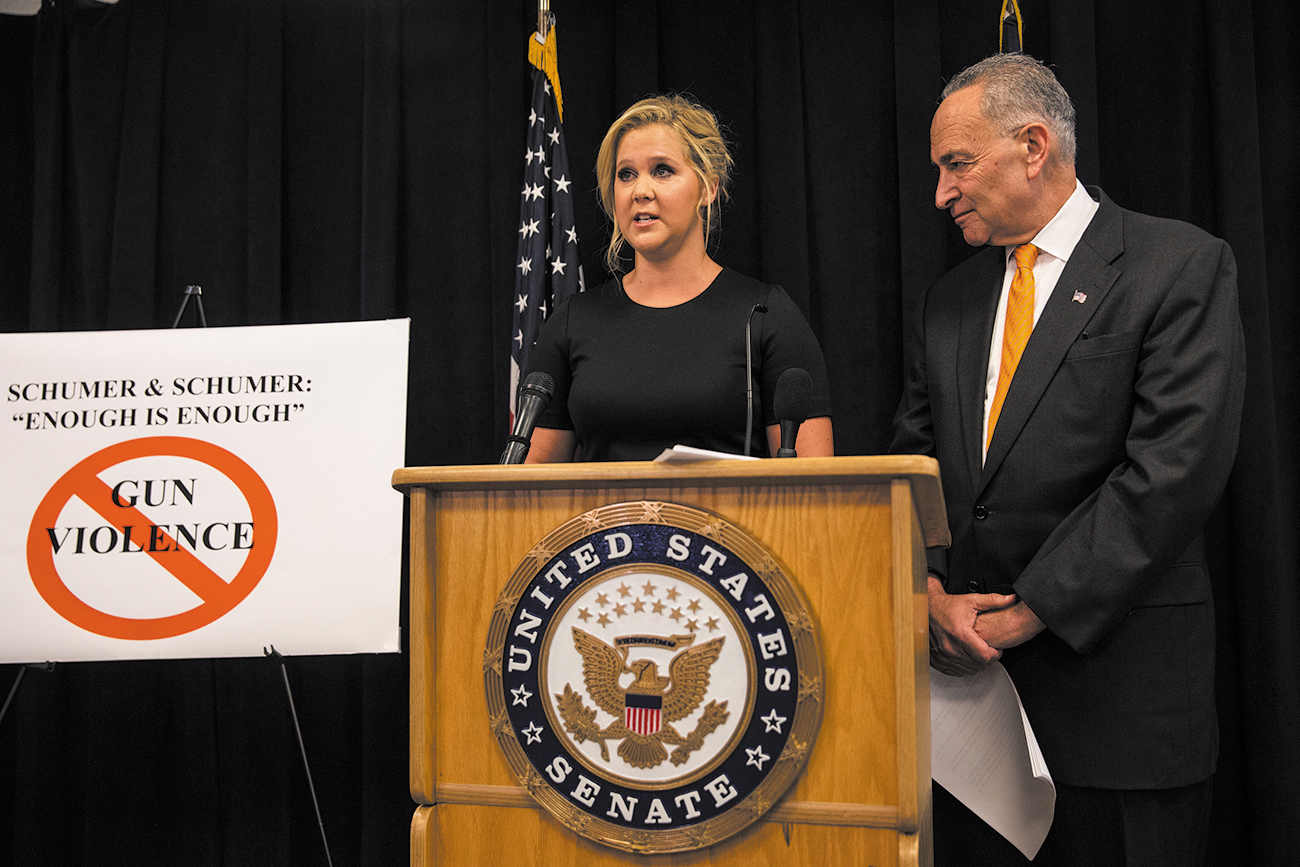

Comedian/actor Amy Schumer boosts her credibility on the issue of gun control by appearing with her cousin, Senator Charles Schumer.

© Andrew Burton/Getty Images

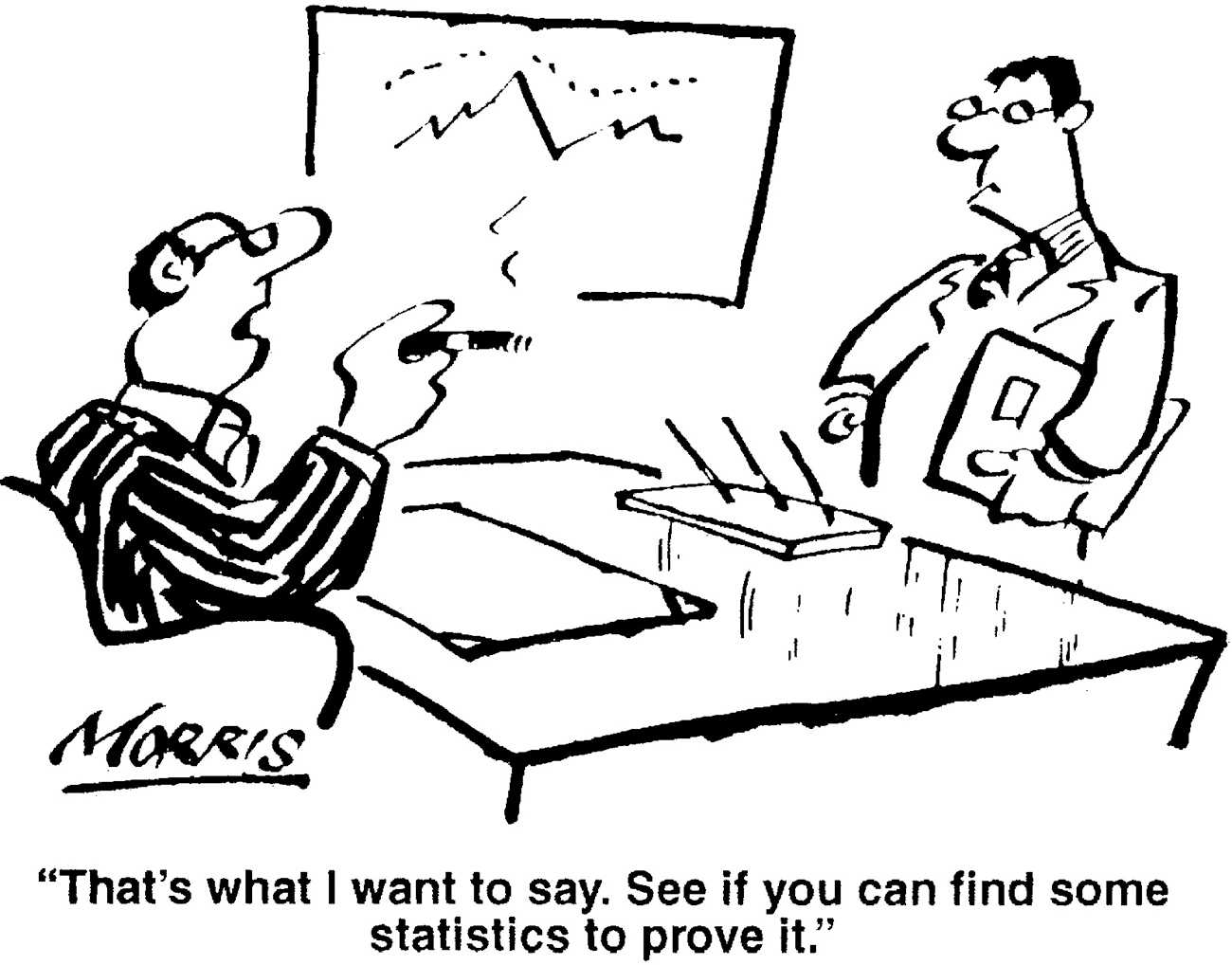

Misuse of Statistics

The misuse of statistics occurs when data are misrepresented. Statistics can be used persuasively in an argument, but sometimes they are distorted—intentionally or unintentionally—to make a point. For example, a classic ad for toothpaste claims that four out of five dentists recommend Crest toothpaste. What the ad neglects to mention is the number of dentists who were questioned. If the company surveyed several thousand dentists, then this statistic would be meaningful. If the company surveyed only ten, however, it would not be.

Misleading statistics can be much subtler (and much more complicated) than the example above. For example, one year, there were 16,653 alcohol-related deaths in the United States. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), 12,892 of these 16,653 alcohol-related deaths involved at least one driver or passenger who was legally drunk. Of the 12,892 deaths, 7,326 were the drivers themselves, and 1,594 were legally drunk pedestrians. The remaining 3,972 fatalities were nonintoxicated drivers, passengers, or nonoccupants. These 3,972 fatalities call the total number into question because the NHTSA does not indicate which drivers were at fault. In other words, if a sober driver ran a red light and killed a legally drunk driver, the NHTSA classified this death as alcohol-related. For this reason, the original number of alcohol-related deaths—16,653—is somewhat misleading. (The statistic becomes even more questionable when you consider that a person is automatically classified as intoxicated if he or she refuses to take a sobriety test.)

Cartoonstock.com

Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc (After This, Therefore Because of This)

The post hoc fallacy asserts that because two events occur closely in time, one event must cause the other. Professional athletes commit the post hoc fallacy all the time. For example, one major league pitcher wears the same shirt every time he has an important game. Because he has won several big games while wearing this shirt, he believes it brings him luck.

Many events seem to follow a sequential pattern even though they actually do not. For example, some people refuse to get a flu shot because they say that the last time they got one, they came down with the flu. Even though there is no scientific basis for this link, many people insist that it is true. (The more probable explanation for this situation is that the flu vaccination takes at least two weeks to take effect, so it is possible for someone to be infected by the flu virus before the vaccine starts working.)

Another health-related issue also illustrates the post hoc fallacy. Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) studied several natural supplements that claim to cure the common cold. Because the study showed that these products were not effective, the FDA ordered the manufacturers to stop making false claims. Despite this fact, however, many people still buy these products. When questioned, they say the medications actually work. Again, the explanation for this phenomenon is simple. Most colds last just a few days. As the FDA pointed out in its report, people who took the medications would have begun feeling better with or without them.

Non Sequitur (It Does Not Follow)

The non sequitur fallacy occurs when a conclusion does not follow from the premises. Frequently, the conclusion is supported by weak or irrelevant evidence—or by no evidence at all. Consider the following statement:

Megan drives an expensive car, so she must be earning a lot of money.

Megan might drive an expensive car, but this is not evidence that she has a high salary. She could, for example, be leasing the car or paying it off over a five-year period, or it could have been a gift.

Non sequiturs are common in political arguments. Consider this statement:

Gangs, drugs, and extreme violence plague today’s prisons. The only way to address this issue is to release all nonviolent offenders as soon as possible.

This assessment of the prison system may be accurate, but it doesn’t follow that because of this situation, all nonviolent offenders should be released immediately.

Scientific arguments also contain non sequiturs. Consider the following statement that was made during a debate on climate change:

Recently, the polar ice caps have thickened, and the temperature of the oceans has stabilized. Obviously, we don’t need to do more to address climate change.

A non sequitur fallacy

NON SEQUITUR © 2006 Wiley Ink, Inc. Dist. By UNIVERSAL UCLICK. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

Even if you accept the facts of this argument, you need to see more evidence before you can conclude that no action against climate change is necessary. For example, the cooling trend could be temporary, or other areas of the earth could still be growing warmer.

Bandwagon Fallacy

The bandwagon fallacy occurs when you try to convince people that something is true because it is widely held to be true. It is easy to see the problem with this line of reasoning. Hundreds of years ago, most people believed that the sun revolved around the earth and that the earth was flat. As we know, the fact that many people held these beliefs did not make them true.

The underlying assumption of the bandwagon fallacy is that the more people who believe something, the more likely it is to be true. Without supporting evidence, however, this form of argument cannot be valid. For example, consider the following statement made by a driver who was stopped by the police for speeding:

Officer, I didn’t do anything wrong. Everyone around me was going the same speed.

As the police officer was quick to point out, the driver’s argument missed the point: he was doing fifty-five miles an hour in a thirty-five-mile-an-hour zone, and the fact that other drivers were also speeding was irrelevant. If the driver had been able to demonstrate that the police officer was mistaken—that he was driving more slowly or that the speed limit was actually sixty miles an hour—then his argument would have had merit. In this case, the fact that other drivers were going the same speed would be relevant because it would support his contention.

The bandwagon fallacy

Cartoonstock.com

Since most people want to go along with the crowd, the bandwagon fallacy can be very effective. For this reason, advertisers use it all the time. For example, a book publisher will say that a book has been on the New York Times bestseller list for ten weeks, and a pharmaceutical company will say that its brand of aspirin outsells other brands four to one. These appeals are irrelevant, however, because they don’t address the central questions: Is the book actually worth reading? Is one brand of aspirin really better than other brands?

EXERCISE 5.12

EXERCISE 5.12

Choose three of the fallacies that you identified in “Immigration Time- Out” for Exercise 5.11. Rewrite each statement in the form of a logical argument.

![]() For more practice, see the LearningCurve on Reasoning and Logical Fallacies in the Launchpad for Practical Argument.

For more practice, see the LearningCurve on Reasoning and Logical Fallacies in the Launchpad for Practical Argument.

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

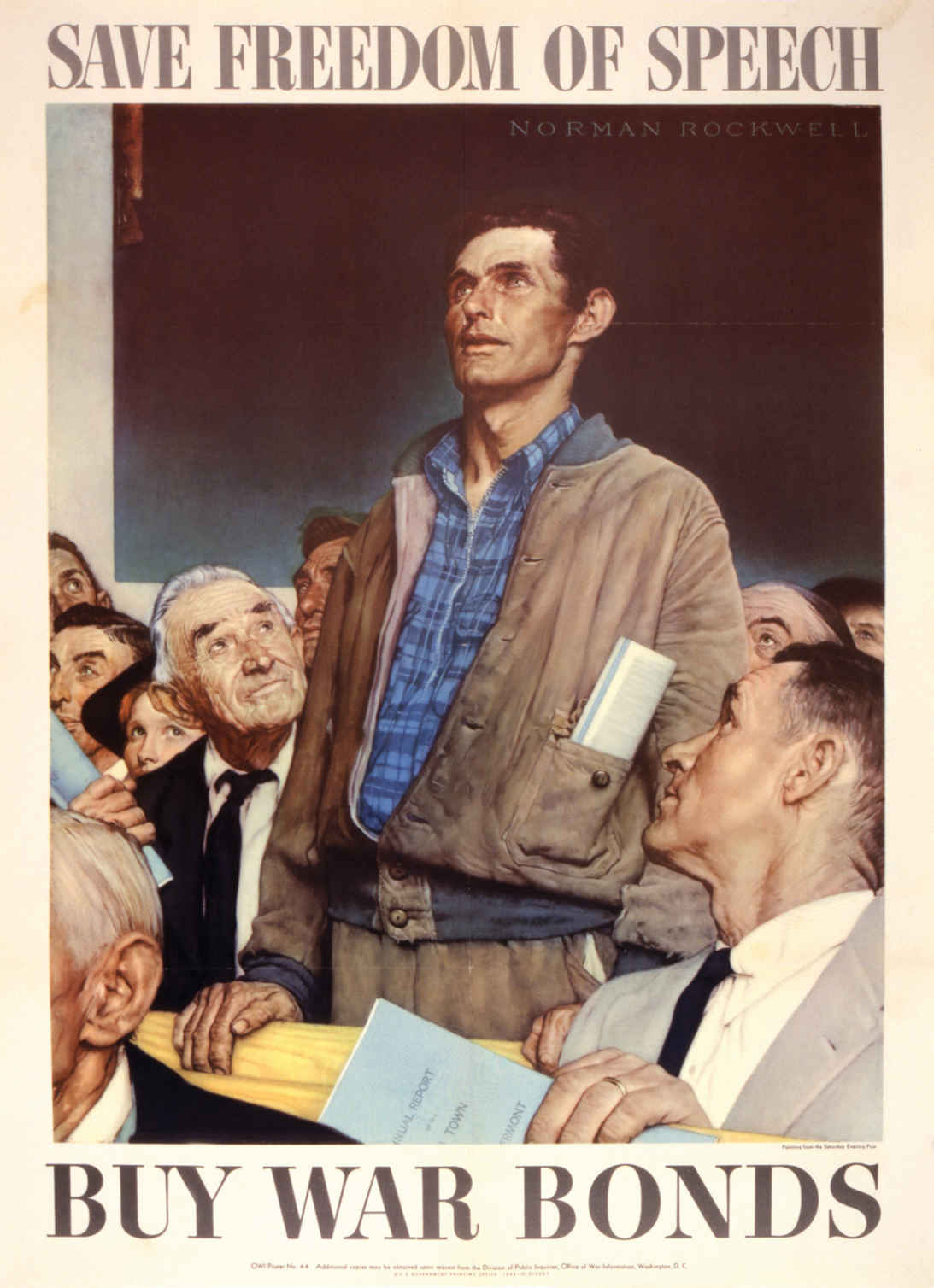

How Free Should Free Speech Be?

Printed by permission of the Norman Rockwell Family Agency. Copyright 1943 the Norman Rockwell Family Entities.

Go back to page 123, and reread the At Issue box that gives background on how free free speech should be. As the following sources illustrate, this question has a number of possible answers.

As you read this source material, you will be asked to answer questions and to complete some simple activities. This work will help you understand both the content and the structure of the sources. When you are finished, you will be ready to write an argument—either inductive or deductive—that takes a new position on how free free speech should actually be.

SOURCES

Thane Rosenbaum, “Should Neo-Nazis Be Allowed Free Speech?,” p. 165

Thane Rosenbaum, “Should Neo-Nazis Be Allowed Free Speech?,” p. 165 Sol Stern, “The Unfree Speech Movement,” p. 168

Sol Stern, “The Unfree Speech Movement,” p. 168 American Association of University Professors, “On Freedom of Expression and Campus Speech Codes,” p. 172

American Association of University Professors, “On Freedom of Expression and Campus Speech Codes,” p. 172 Wendy Kaminer, “Progressive Ideas Have Killed Free Speech on Campus,” p. 175

Wendy Kaminer, “Progressive Ideas Have Killed Free Speech on Campus,” p. 175 Judith Shulevitz, “In College and Hiding from Scary Ideas,” p. 178

Judith Shulevitz, “In College and Hiding from Scary Ideas,” p. 178 Eric Posner, “Universities Are Right to Crack Down on Speech and Behavior,” p. 183

Eric Posner, “Universities Are Right to Crack Down on Speech and Behavior,” p. 183

This article originally appeared on TheDailyBeast.com on January 1, 2014.

THANE ROSENBAUM

SHOULD NEO-NAZIS BE ALLOWED FREE SPEECH?

Over the past several weeks, free speech has gotten costlier—at least in France and Israel.1

In France, Dieudonne M’Bala M’Bala, an anti-Semitic stand-up comic infamous for popularizing the quenelle, an inverted Nazi salute, was banned from performing in two cities. M’Bala M’Bala has been repeatedly fined for hate speech, and this was not the first time his act was perceived as a threat to public order.2

Meanwhile, Israel’s parliament is soon to pass a bill outlawing the word Nazi for non-educational purposes. Indeed, any slur against another that invokes the Third Reich could land the speaker in jail for six months with a fine of $29,000. The Israelis are concerned about both the rise of anti-Semitism globally, and the trivialization of the Holocaust—even locally.3

To Americans, these actions in France and Israel seem positively un-democratic. The First Amendment would never prohibit the quenelle, regardless of its symbolic meaning. And any lover of Seinfeld would regard banning the “Soup Nazi” episode as scandalously un-American. After all, in 1977 a federal court upheld the right of neo-Nazis to goose-step right through the town of Skokie, Illinois, which had a disproportionately large number of Holocaust survivors as residents. And more recently, the Supreme Court upheld the right of a church group opposed to gays serving in the military to picket the funeral of a dead marine with signs that read, “God Hates Fags.”4

While what is happening in France and Israel is wholly foreign to Americans, perhaps it’s time to consider whether these and other countries may be right. Perhaps America’s fixation on free speech has gone too far.5

Actually, the United States is an outlier among democracies in granting such generous free speech guarantees. Six European countries, along with Brazil, prohibit the use of Nazi symbols and flags. Many more countries have outlawed Holocaust denial. Indeed, even encouraging racial discrimination in France is a crime. In pluralistic nations like these with clashing cultures and historical tragedies not shared by all, mutual respect and civility helps keep the peace and avoids unnecessary mental trauma.6

Yet, even in the United States, free speech is not unlimited. Certain proscribed categories have always existed—libel, slander and defamation, obscenity, “fighting words,” and the “incitement of imminent lawlessness”—where the First Amendment does not protect the speaker, where the right to speak is curtailed for reasons of general welfare and public safety. There is no freedom to shout “fire” in a crowded theater. Hate crime statutes exist in many jurisdictions where bias-motivated crimes are given more severe penalties. In 2003, the Supreme Court held that speech intended to intimidate, such as cross burning, might not receive First Amendment protection.7

Yet, the confusion is that in placing limits on speech we privilege physical over emotional harm. Indeed, we have an entire legal system, and an attitude toward speech, that takes its cue from a nursery rhyme: “Sticks and stones can break my bones but names can never hurt me.”8

All of us know, however, and despite what we tell our children, names do, indeed, hurt. And recent studies in universities such as Purdue, UCLA, Michigan, Toronto, Arizona, Maryland, and Macquarie University in New South Wales show, among other things, through brain scans and controlled studies with participants who were subjected to both physical and emotional pain, that emotional harm is equal in intensity to that experienced by the body, and is even more long-lasting and traumatic. Physical pain subsides; emotional pain, when recalled, is relived.9

Pain has a shared circuitry in the human brain, and it makes no distinction between being hit in the face and losing face (or having a broken heart) as a result of bereavement, betrayal, social exclusion, and grave insult. Emotional distress can, in fact, make the body sick. Indeed, research has shown that pain relief medication can work equally well for both physical and emotional injury.10

We impose speed limits on driving and regulate food and drugs because we know that the costs of not doing so can lead to accidents and harm. Why should speech be exempt from public welfare concerns when its social costs can be even more injurious?11

“We impose speed limits on driving and regulate food and drugs because we know that the costs of not doing so can lead to accidents and harm.”

In the marketplace of ideas, there is a difference between trying to persuade and trying to injure. One can object to gays in the military without ruining the one moment a father has to bury his son; neo-Nazis can long for the Third Reich without re-traumatizing Hitler’s victims; one can oppose Affirmative Action without burning a cross on an African-American’s lawn.12

Of course, everything is a matter of degree. Juries are faced with similar ambiguities when it comes to physical injury. No one knows for certain whether the plaintiff wearing a neck brace can’t actually run the New York Marathon. We tolerate the fake slip and fall, but we feel absolutely helpless in evaluating whether words and gestures intended to harm actually do cause harm. Jurors are as capable of working through these uncertainties in the area of emotional harms as they are in the realm of physical injury.13

Free speech should not stand in the way of common decency. No right should be so freely and recklessly exercised that it becomes an impediment to civil society, making it so that others are made to feel less free, their private space and peace invaded, their sensitivities cruelly trampled upon.14

![]() AT ISSUE: HOW FREE SHOULD FREE SPEECH BE?

AT ISSUE: HOW FREE SHOULD FREE SPEECH BE?

- Rosenbaum waits until the end of paragraph 6 to state his thesis. Why? What information does he include in paragraphs 1–5? How does this material set the stage for the rest of the essay?

- Rosenbaum develops his argument with both inductive and deductive reasoning. Where does he use each strategy?

- What evidence does Rosenbaum use to support his thesis? Should he have included more evidence? If so, what kind?

- In paragraph 11, Rosenbaum makes a comparison between regulating free speech and regulating driving and food and drugs. How strong is this analogy? At what points (if any) does this comparison break down?

- Where does Rosenbaum address arguments against his position? Does he refute these arguments? What other opposing arguments could he have addressed?

- What point does Rosenbaum reinforce in his conclusion? What other points could he have emphasized?

This op-ed originally ran in the Wall Street Journal on September 24, 2014.

SOL STERN

THE UNFREE SPEECH MOVEMENT

This fall the University of California at Berkeley is celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Free Speech Movement, a student-led protest against campus restrictions on political activities that made headlines and inspired imitators around the country. I played a small part in the Free Speech Movement, and some of those returning for the reunion were once my friends, but I won’t be joining them.1

Though the movement promised greater intellectual and political freedom on campus, the result has been the opposite. The great irony is that while Berkeley now honors the memory of the Free Speech Movement, it exercises more thought control over students than the hated institution that we rose up against half a century ago.2

We early-1960s radicals believed ourselves anointed as a new “tell it like it is” generation. We promised to transcend the “smelly old orthodoxies” (in George Orwell’s phrase) of Cold War liberalism and class-based, authoritarian leftism. Leading students into the university administration building for the first mass protest, Mario Savio, the Free Speech Movement’s brilliant leader from Queens, New York, famously said: “There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious—makes you so sick at heart—that you can’t take part…. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all.”3

The Berkeley “machine” now promotes Free Speech Movement kitsch. The steps in front of Sproul Hall, the central administration building where more than 700 students were arrested on Dec. 2, 1964, have been renamed the Mario Savio Steps. One of the campus dining halls is called the Free Speech Movement Cafe, its walls covered with photographs and mementos of the glorious semester of struggle. The university requires freshmen to read an admiring biography of Savio, who died in 1996, written by New York University professor and Berkeley graduate Robert Cohen.4

Yet intellectual diversity is hardly embraced. Every undergraduate undergoes a form of indoctrination with a required course on the “theoretical or analytical issues relevant to understanding race, culture, and ethnicity in American society,” administered by the university’s Division of Equity and Inclusion.5

How did this Orwellian inversion occur? It happened in part because the Free Speech Movement’s fight for free speech was always a charade. The struggle was really about using the campus as a base for radical politics. I was a 27-year-old New Left graduate student at the time. Savio was a 22-year-old sophomore. He liked to compare the Free Speech Movement to the civil-rights struggle—conflating the essentially liberal Berkeley administration with the Bull Connors of the racist South.6

During one demonstration Savio suggested that the campus cops who had arrested a protesting student were “poor policemen” who only “have a job to do.” Another student then shouted out: “Just like Eichmann.” “Yeah. Very good. It’s very, you know, like Adolf Eichmann,” Savio replied. “He had a job to do. He fit into the machinery.”7

I realized years later that this moment may have been the beginning of the 1960s radicals’ perversion of ordinary political language, like the spelling “Amerika” or seeing hope and progress in Third World dictatorships.8

Before that 1964–65 academic year, most of us radical students could not have imagined a campus rebellion. Why revolt against an institution that until then offered such a pleasant sanctuary? But then Berkeley administrators made an incredibly stupid decision to establish new rules regarding political activities on campus. Student clubs were no longer allowed to set up tables in front of the Bancroft Avenue campus entrance to solicit funds and recruit new members.9

The clubs had used this 40-foot strip of sidewalk for years on the assumption that it was the property of the City of Berkeley and thus constitutionally protected against speech restrictions. But the university claimed ownership to justify the new rules. When some students refused to comply, the administration compounded its blunder by resorting to the campus police. Not surprisingly, the students pushed back, using civil-disobedience tactics learned fighting for civil rights in the South.10

The Free Speech Movement was born on Oct. 1, 1964, when police tried to arrest a recent Berkeley graduate, Jack Weinberg, who was back on campus after a summer as a civil-rights worker in Mississippi. He had set up a table on the Bancroft strip for the Berkeley chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Dozens of students spontaneously sat down around the police car, preventing it from leaving the campus. A 32-hour standoff ensued, with hundreds of students camped around the car.11

Mario Savio, also back from Mississippi, took off his shoes, climbed onto the roof of the police car, and launched into an impromptu speech explaining why the students had to resist the immoral new rules. Thus began months of sporadic protests, the occupation of Sproul Hall on Dec. 2 (ended by mass arrests), national media attention, and Berkeley’s eventual capitulation.12

That should have ended the matter. Savio soon left the political arena, saying that he had no interest in becoming a permanent student leader. But others had mastered the new world of political theater, understood the weakness of American liberalism, and soon turned their ire on the Vietnam War.13

“But others had mastered the new world of political theater, understood the weakness of American liberalism, and soon turned their ire on the Vietnam War.”

Mario Savio at a victory rally on the University of California campus in Berkeley (December 9, 1964)

AP Photo.

The radical movement that the Free Speech Movement spawned eventually descended into violence and mindless anti-Americanism. The movement waned in the 1970s as the war wound down—but by then protesters had begun their infiltration of university faculties and administrations they had once decried. “Tenured radicals,” in New Criterion editor Roger Kimball’s phrase, now dominate most professional organizations in the humanities and social studies. Unlike our old liberal professors, who dealt respectfully with the ideas advanced by my generation of New Left students, today’s radical professors insist on ideological conformity and don’t take kindly to dissent by conservative students. Visits by speakers who might not toe the liberal line—recently including former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Islamism critic Ayaan Hirsi Ali—spark protests and letter-writing campaigns by students in tandem with their professors until the speaker withdraws or the invitation is canceled.14

On Oct. 1 at Berkeley, by contrast, one of the honored speakers at the Free Speech Movement anniversary rally on Sproul Plaza will be Bettina Aptheker, who is now a feminist-studies professor at the University of California at Santa Cruz.15

Writing in the Berkeley alumni magazine about the anniversary, Ms. Aptheker noted that the First Amendment was “written by white, propertied men in the 18th century, who never likely imagined that it might apply to women, and/or people of color, and/or all those who were not propertied, and even, perhaps, not citizens, and/or undocumented immigrants…. In other words, freedom of speech is a Constitutional guarantee, but who gets to exercise it without the chilling restraints of censure depends very much on one’s location in the political and social cartography. We [Free Speech Movement] veterans were too young and inexperienced in 1964 to know this, but we do now, and we speak with a new awareness, a new consciousness, and a new urgency that the wisdom of a true freedom is inexorably tied to who exercises power and for what ends.” Read it and weep—for the Free Speech Movement anniversary, for the ideal of an intellectually open university, and for America.16

![]() AT ISSUE: HOW FREE SHOULD FREE SPEECH BE?

AT ISSUE: HOW FREE SHOULD FREE SPEECH BE?

- In your own words, summarize Stern’s thesis. Where does he state it?

- At what point (or points) in the essay does Stern appeal to ethos? How effective is this appeal?

- In paragraph 4, Stern says, “The Berkeley ‘machine’ now promotes Free Speech Movement kitsch.” First, look up the meaning of kitsch. Then, explain what Stern means by this statement.

- Stern supports his points with examples drawn from his own experience. Is this enough? What other kinds of evidence could he have used?

- In paragraph 5, Stern says that every undergraduate at Berkeley “undergoes a form of indoctrination.” What does he mean? Does Stern make a valid point, or is he begging the question?

- Why does Stern discuss Bettina Aptheker in paragraphs 15–16? Could he be accused of making an ad hominem attack? Why or why not?

This code came out of a June 1992 meeting of the American Association of University Professors.

AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF UNIVERSITY PROFESSORS

ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND CAMPUS SPEECH CODES

Freedom of thought and expression is essential to any institution of higher learning. Universities and colleges exist not only to transmit existing knowledge. Equally, they interpret, explore, and expand that knowledge by testing the old and proposing the new.1

This mission guides learning outside the classroom quite as much as in class, and often inspires vigorous debate on those social, economic, and political issues that arouse the strongest passions. In the process, views will be expressed that may seem to many wrong, distasteful, or offensive. Such is the nature of freedom to sift and winnow ideas.2

On a campus that is free and open, no idea can be banned or forbidden. No viewpoint or message may be deemed so hateful or disturbing that it may not be expressed.3

“On a campus that is free and open, no idea can be banned or forbidden.”

Universities and colleges are also communities, often of a residential character. Most campuses have recently sought to become more diverse, and more reflective of the larger community, by attracting students, faculty, and staff from groups that were historically excluded or underrepresented. Such gains as they have made are recent, modest, and tenuous. The campus climate can profoundly affect an institution’s continued diversity. Hostility or intolerance to persons who differ from the majority (especially if seemingly condoned by the institution) may undermine the confidence of new members of the community. Civility is always fragile and can easily be destroyed.4

In response to verbal assaults and use of hateful language some campuses have felt it necessary to forbid the expression of racist, sexist, homophobic, or ethnically demeaning speech, along with conduct or behavior that harasses. Several reasons are offered in support of banning such expression. Individuals and groups that have been victims of such expression feel an understandable outrage. They claim that the academic progress of minority and majority alike may suffer if fears, tensions, and conflicts spawned by slurs and insults create an environment inimical to learning. These arguments, grounded in the need to foster an atmosphere respectful of and welcome to all persons, strike a deeply responsive chord in the academy. But, while we can acknowledge both the weight of these concerns and the thoughtfulness of those persuaded of the need for regulation, rules that ban or punish speech based upon its content cannot be justified. An institution of higher learning fails to fulfill its mission if it asserts the power to proscribe ideas—and racial or ethnic slurs, sexist epithets, or homophobic insults almost always express ideas, however repugnant. Indeed, by proscribing any ideas, a university sets an example that profoundly disserves its academic mission. Some may seek to defend a distinction between the regulation of the content of speech and the regulation of the manner (or style) of speech. We find this distinction untenable in practice because offensive style or opprobrious phrases may in fact have been chosen precisely for their expressive power. As the United States Supreme Court has said in the course of rejecting criminal sanctions for offensive words: Words are often chosen as much for their emotive as their cognitive force. We cannot sanction the view that the Constitution, while solicitous of the cognitive content of individual speech, has little or no regard for that emotive function which, practically speaking, may often be the more important element of the overall message sought to be communicated. The line between substance and style is thus too uncertain to sustain the pressure that will inevitably be brought to bear upon disciplinary rules that attempt to regulate speech. Proponents of speech codes sometimes reply that the value of emotive language of this type is of such a low order that, on balance, suppression is justified by the harm suffered by those who are directly affected, and by the general damage done to the learning environment. Yet a college or university sets a perilous course if it seeks to differentiate between high-value and low-value speech, or to choose which groups are to be protected by curbing the speech of others. A speech code unavoidably implies an institutional competence to distinguish permissible expression of hateful thought from what is proscribed as thoughtless hate. Institutions would also have to justify shielding some, but not other, targets of offensive language—not to political preference, to religious but not to philosophical creed, or perhaps even to some but not to other religious affiliations. Starting down this path creates an even greater risk that groups not originally protected may later demand similar solicitude—demands the institution that began the process of banning some speech is ill equipped to resist.5

Distinctions of this type are neither practicable nor principled; their very fragility underscores why institutions devoted to freedom of thought and expression ought not adopt an institutionalized coercion of silence.6

Moreover, banning speech often avoids consideration of means more compatible with the mission of an academic institution by which to deal with incivility, intolerance, offensive speech, and harassing behavior:7

- Institutions should adopt and invoke a range of measures that penalize conduct and behavior, rather than speech, such as rules against defacing property, physical intimidation or harassment, or disruption of campus activities. All members of the campus community should be made aware of such rules, and administrators should be ready to use them in preference to speech-directed sanctions.

- Colleges and universities should stress the means they use best—to educate—including the development of courses and other curricular and co-curricular experiences designed to increase student understanding and to deter offensive or intolerant speech or conduct. Such institutions should, of course, be free (indeed encouraged) to condemn manifestations of intolerance and discrimination, whether physical or verbal.

- The governing board and the administration have a special duty not only to set an outstanding example of tolerance, but also to challenge boldly and condemn immediately serious breaches of civility.

- Members of the faculty, too, have a major role; their voices may be critical in condemning intolerance, and their actions may set examples for understanding, making clear to their students that civility and tolerance are hallmarks of educated men and women.

- Student personnel administrators have in some ways the most demanding role of all, for hate speech occurs most often in dormitories, locker-rooms, cafeterias, and student centers. Persons who guide this part of campus life should set high standards of their own for tolerance and should make unmistakably clear the harm that uncivil or intolerant speech inflicts.

To some persons who support speech codes, measures like these—relying as they do on suasion rather than sanctions—may seem inadequate. But freedom of expression requires toleration of “ideas we hate,” as Justice Holmes put it. The underlying principle does not change because the demand is to silence a hateful speaker, or because it comes from within the academy. Free speech is not simply an aspect of the educational enterprise to be weighed against other desirable ends. It is the very precondition of the academic enterprise itself.8

![]() AT ISSUE: HOW FREE SHOULD FREE SPEECH BE?

AT ISSUE: HOW FREE SHOULD FREE SPEECH BE?

- The writers of this statement rely primarily on deductive reasoning. Construct a syllogism that includes the selection’s major premise, minor premise, and conclusion.

- At what audience is this statement aimed—students, instructors, administrators, or the general public? How do you know?

- What problem do the writers address? Where do they present their solution?

- In paragraph 5, the writers discuss the major arguments against their position. Why do they address opposing arguments so early in the selection? How effectively do the writers refute these arguments?

- Paragraph 7 is followed by a numbered list. What information is in this list? Why did the writers decide to set it off in this way?

- What do the writers mean when they say that free speech “is the very precondition of the academic exercise itself” (para. 8)?

This essay first appeared in the Washington Post on February 20, 2015.

WENDY KAMINER

PROGRESSIVE IDEAS HAVE KILLED FREE SPEECH ON CAMPUS

Is an academic discussion of free speech potentially traumatic? A recent panel for Smith College alumnae aimed at “challenging the ideological echo chamber” elicited this ominous “trigger/content warning” when a transcript appeared in the campus newspaper: “Racism/racial slurs, ableist slurs, antisemitic language, anti-Muslim/Islamophobic language, anti-immigrant language, sexist/misogynistic slurs, references to race-based violence, references to antisemitic violence.”1

No one on this panel, in which I participated, trafficked in slurs. So what prompted the warning?2

Smith President Kathleen McCartney had joked, “We’re just wild and crazy, aren’t we?” In the transcript, “crazy” was replaced by the notation: “[ableist slur].”3

One of my fellow panelists mentioned that the State Department had for a time banned the words “jihad,” “Islamist,” and “caliphate”—which the transcript flagged as “anti-Muslim/Islamophobic language.”4

I described the case of a Brandeis professor disciplined for saying “wetback” while explaining its use as a pejorative. The word was replaced in the transcript by “[anti-Latin@/anti-immigrant slur].” Discussing the teaching of Huckleberry Finn, I questioned the use of euphemisms such as “the n-word” and, in doing so, uttered that forbidden word. I described what I thought was the obvious difference between quoting a word in the context of discussing language, literature, or prejudice and hurling it as an epithet.5

Two of the panelists challenged me. The audience of 300 to 400 people listened to our spirited, friendly debate—and didn’t appear angry or shocked. But back on campus, I was quickly branded a racist, and I was charged in the Huffington Post with committing “an explicit act of racial violence.” McCartney subsequently apologized that “some students and faculty were hurt” and made to “feel unsafe” by my remarks.6

Unsafe? These days, when students talk about threats to their safety and demand access to “safe spaces,” they’re often talking about the threat of un-welcome speech and demanding protection from the emotional disturbances sparked by unsettling ideas. It’s not just rape that some women on campus fear: It’s discussions of rape. At Brown University, a scheduled debate between two feminists about rape culture was criticized for, as the Brown Daily Herald put it, undermining “the University’s mission to create a safe and supportive environment for survivors.” In a school-wide e-mail, Brown President Christina Paxon emphasized her belief in the existence of rape culture and invited students to an alternative lecture, to be given at the same time as the debate. And the Daily Herald reported that students who feared being “attacked by the viewpoints” offered at the debate could instead “find a safe space” among “sexual assault peer educators, women peer counselors and staff” during the same time slot. Presumably they all shared the same viewpoints and could be trusted not to “attack” anyone with their ideas.7

How did we get here? How did a verbal defense of free speech become tantamount to a hate crime and offensive words become the equivalent of physical assaults?8

You can credit—or blame—progressives for this enthusiastic embrace of censorship. It reflects, in part, the influence of three popular movements dating back decades: the feminist anti-porn crusades, the pop-psychology recovery movement, and the emergence of multiculturalism on college campuses.9

“How did a verbal defense of free speech become tantamount to a hate crime and offensive words become the equivalent of physical assaults?”

In the 1980s, law professor Catharine MacKinnon and writer Andrea Dworkin showed the way, popularizing a view of free speech as a barrier to equality. These two impassioned feminists framed pornography—its production, distribution, and consumption—as an assault on women. They devised a novel definition of pornography as a violation of women’s civil rights, and championed a model anti-porn ordinance that would authorize civil actions by any woman “aggrieved” by pornography. In 1984, the city of Indianapolis adopted the measure, defining pornography as a “discriminatory practice,” but it was quickly struck down in federal court as unconstitutional. “Indianapolis justifies the ordinance on the ground that pornography affects thoughts,” the court noted. “This is thought control.”10

So MacKinnnon and Dworkin lost that battle, but their successors are winning the war. Their view of allegedly offensive or demeaning speech as a civil rights violation, and their conflation of words and actions, have helped shape campus speech and harassment codes and nurtured progressive hostility toward free speech.11

The recovery movement, which flourished in the late ’80s and early ’90s, adopted a similarly dire view of unwelcome speech. Words wound, anti-porn feminists and recovering co-dependents agreed. Self-appointed recovery experts, such as the best-selling author John Bradshaw, promoted the belief that most of us are victims of abuse, in one form or another. They broadened the definition of abuse to include a range of common, normal childhood experiences, including being chastised or ignored by your parents on occasion. From this perspective, we are all fragile and easily damaged by presumptively hurtful speech, and censorship looks like a moral necessity.12

These ideas were readily absorbed on college campuses embarking on a commendable drive for diversity. Multiculturalists sought to protect historically disadvantaged students from speech considered racist, sexist, homophobic or otherwise discriminatory. Like abuse, oppression was defined broadly. I remember the first time, in the early ’90s, that I heard a Harvard student describe herself as oppressed, as a woman of color. She hadn’t been systematically deprived of fundamental rights and liberties. After all, she’d been admitted to Harvard. But she had been offended and unsettled by certain attitudes and remarks. Did she have good reason to take offense? That was an irrelevant question. Popular therapeutic culture defined verbal “assaults” and other forms of discrimination by the subjective, emotional responses of self-proclaimed victims.13

This reliance on subjectivity, in the interest of equality, is a recipe for arbitrary, discriminatory enforcement practices, with far-reaching effects on individual liberty. The tendency to take subjective allegations of victimization at face value—instrumental in contemporary censorship campaigns—also leads to the presumption of guilt and disregard for due process in the progressive approach to alleged sexual assaults on campus.14

This is a dangerously misguided approach to justice. “Feeling realities” belong in a therapist’s office. Incorporated into laws and regulations, they lead to the soft authoritarianism that now governs many American campuses. Instead of advancing equality, it’s teaching future generations of leaders the “virtues” of autocracy.15

![]() AT ISSUE: HOW FREE SHOULD FREE SPEECH BE?

AT ISSUE: HOW FREE SHOULD FREE SPEECH BE?

- Should Kaminer have given more background information about the problem she discusses? What additional information could she have provided?

- Kaminer devotes the first six paragraphs of her essay to describing a panel discussion. Why do you think she begins her essay in this way? How does this discussion prepare readers for the rest of the essay?

- In paragraph 8, Kaminer asks two questions. What is the function of these questions?

- According to Kaminer, what are “feeling realities” (para. 15)? In what sense are “feeling realities” harmful?

- Does Kaminer ever establish that the situation she discusses is widespread enough to be a problem? Could she be accused of setting up a straw man?

- What does Kaminer want to accomplish? Is her purpose to convince readers of something? To move them to action? What is your reaction to her essay?

This opinion piece was originally published on March 21, 2015, in the New York Times.

JUDITH SHULEVITZ

IN COLLEGE AND HIDING FROM SCARY IDEAS

Katherine Byron, a senior at Brown University and a member of its Sexual Assault Task Force, considers it her duty to make Brown a safe place for rape victims, free from anything that might prompt memories of trauma.1

So when she heard last fall that a student group had organized a debate about campus sexual assault between Jessica Valenti, the founder of feministing.com, and Wendy McElroy, a libertarian, and that Ms. McElroy was likely to criticize the term “rape culture,” Ms. Byron was alarmed. “Bringing in a speaker like that could serve to invalidate people’s experiences,” she told me. It could be “damaging.”2

Ms. Byron and some fellow task force members secured a meeting with administrators. Not long after, Brown’s president, Christina H. Paxson, announced that the university would hold a simultaneous, competing talk to provide “research and facts” about “the role of culture in sexual assault.” Meanwhile, student volunteers put up posters advertising that a “safe space” would be available for anyone who found the debate too upsetting.3

The safe space, Ms. Byron explained, was intended to give people who might find comments “troubling” or “triggering,” a place to recuperate. The room was equipped with cookies, coloring books, bubbles, Play-Doh, calming music, pillows, blankets, and a video of frolicking puppies, as well as students and staff members trained to deal with trauma. Emma Hall, a junior, rape survivor, and “sexual assault peer educator” who helped set up the room and worked in it during the debate, estimates that a couple of dozen people used it. At one point she went to the lecture hall—it was packed—but after a while, she had to return to the safe space. “I was feeling bombarded by a lot of viewpoints that really go against my dearly and closely held beliefs,” Ms. Hall said.4

Safe spaces are an expression of the conviction, increasingly prevalent among college students, that their schools should keep them from being “bombarded” by discomfiting or distressing viewpoints. Think of the safe space as the live-action version of the better-known trigger warning, a notice put on top of a syllabus or an assigned reading to alert students to the presence of potentially disturbing material.5

Some people trace safe spaces back to the feminist consciousness-raising groups of the 1960s and 1970s, others to the gay and lesbian movement of the early 1990s. In most cases, safe spaces are innocuous gatherings of like-minded people who agree to refrain from ridicule, criticism, or what they term microaggressions—subtle displays of racial or sexual bias—so that everyone can relax enough to explore the nuances of, say, a fluid gender identity. As long as all parties consent to such restrictions, these little islands of self-restraint seem like a perfectly fine idea.6

But the notion that ticklish conversations must be scrubbed clean of controversy has a way of leaking out and spreading. Once you designate some spaces as safe, you imply that the rest are unsafe. It follows that they should be made safer.7

“As long as all parties consent to such restrictions, these little islands of self-restraint seem like a perfectly fine idea.”

This logic clearly informed a campaign undertaken this fall by a Columbia University student group called Everyone Allied Against Homophobia that consisted of slipping a flier under the door of every dorm room on campus. The headline of the flier stated, “I want this space to be a safer space.” The text below instructed students to tape the fliers to their windows. The group’s vice president then had the flier published in the Columbia Daily Spectator, the student newspaper, along with an editorial asserting that “making spaces safer is about learning how to be kind to each other.”8

A junior named Adam Shapiro decided he didn’t want his room to be a safer space. He printed up his own flier calling it a dangerous space and had that, too, published in the Columbia Daily Spectator. “Kindness alone won’t allow us to gain more insight into truth,” he wrote. In an interview, Mr. Shapiro said, “If the point of a safe space is therapy for people who feel victimized by traumatization, that sounds like a great mission.” But a safe-space mentality has begun infiltrating classrooms, he said, making both professors and students loath to say anything that might hurt someone’s feelings. “I don’t see how you can have a therapeutic space that’s also an intellectual space,” he said.9

I’m old enough to remember a time when college students objected to providing a platform to certain speakers because they were deemed politically unacceptable. Now students worry whether acts of speech or pieces of writing may put them in emotional peril. Two weeks ago, students at Northwestern University marched to protest an article by Laura Kipnis, a professor in the university’s School of Communication. Professor Kipnis had criticized— O.K., ridiculed—what she called the sexual paranoia pervading campus life.10

The protesters carried mattresses and demanded that the administration condemn the essay. One student complained that Professor Kipnis was “erasing the very traumatic experience” of victims who spoke out. An organizer of the demonstration said, “we need to be setting aside spaces to talk” about “victimblaming.” Last Wednesday, Northwestern’s president, Morton O. Schapiro, wrote an op-ed article in the Wall Street Journal affirming his commitment to academic freedom. But plenty of others at universities are willing to dignify students’ fears, citing threats to their stability as reasons to cancel debates, disinvite commencement speakers, and apologize for so-called mistakes.11

At Oxford University’s Christ Church college in November, the college censors (a “censor” being more or less the Oxford equivalent of an undergraduate dean) canceled a debate on abortion after campus feminists threatened to disrupt it because both would-be debaters were men. “I’m relieved the censors have made this decision,” said the treasurer of Christ Church’s student union, who had pressed for the cancellation. “It clearly makes the most sense for the safety—both physical and mental—of the students who live and work in Christ Church.”12

A year and a half ago, a Hampshire College student group disinvited an Afrofunk band that had been attacked on social media for having too many white musicians; the vitriolic discussion had made students feel “unsafe.”13

Last fall, the president of Smith College, Kathleen McCartney, apologized for causing students and faculty to be “hurt” when she failed to object to a racial epithet uttered by a fellow panel member at an alumnae event in New York. The offender was the free-speech advocate Wendy Kaminer, who had been arguing against the use of the euphemism “the n-word” when teaching American history or The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. In the uproar that followed, the Student Government Association wrote a letter declaring that “if Smith is unsafe for one student, it is unsafe for all students.”14

“It’s amazing to me that they can’t distinguish between racist speech and speech about racist speech, between racism and discussions of racism,” Ms. Kaminer said in an email.15

The confusion is telling, though. It shows that while keeping college-level discussions “safe” may feel good to the hypersensitive, it’s bad for them and for everyone else. People ought to go to college to sharpen their wits and broaden their field of vision. Shield them from unfamiliar ideas, and they’ll never learn the discipline of seeing the world as other people see it. They’ll be unprepared for the social and intellectual headwinds that will hit them as soon as they step off the campuses whose climates they have so carefully controlled. What will they do when they hear opinions they’ve learned to shrink from? If they want to change the world, how will they learn to persuade people to join them?16

Only a few of the students want stronger anti-hate-speech codes. Mostly they ask for things like mandatory training sessions and stricter enforcement of existing rules. Still, it’s disconcerting to see students clamor for a kind of intrusive supervision that would have outraged students a few generations ago. But those were hardier souls. Now students’ needs are anticipated by a small army of service professionals—mental health counselors, student-life deans, and the like. This new bureaucracy may be exacerbating students’ “self-infantilization,” as Judith Shapiro, the former president of Barnard College, suggested in an essay for Inside Higher Ed.17

But why are students so eager to self-infantilize? Their parents should probably share the blame. Eric Posner, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, wrote on Slate last month that although universities cosset students more than they used to, that’s what they have to do, because today’s undergraduates are more puerile than their predecessors. “Perhaps overprogrammed children engineered to the specifications of college admissions offices no longer experience the risks and challenges that breed maturity,” he wrote. But “if college students are children, then they should be protected like children.”18

“Their parents should probably share the blame.”

Another reason students resort to the quasi-medicalized terminology of trauma is that it forces administrators to respond. Universities are in a double bind. They’re required by two civil-rights statutes, Title VII and Title IX, to ensure that their campuses don’t create a “hostile environment” for women and other groups subject to harassment. However, universities are not supposed to go too far in suppressing free speech, either. If a university cancels a talk or punishes a professor and a lawsuit ensues, history suggests that the university will lose. But if officials don’t censure or don’t prevent speech that may inflict psychological damage on a member of a protected class, they risk fostering a hostile environment and prompting an investigation. As a result, students who say they feel unsafe are more likely to be heard than students who demand censorship on other grounds.19

The theory that vulnerable students should be guaranteed psychological security has roots in a body of legal thought elaborated in the 1980s and 1990s and still read today. Feminist and anti-racist legal scholars argued that the First Amendment should not safeguard language that inflicted emotional injury through racist or sexist stigmatization. One scholar, Mari J. Matsuda, was particularly insistent that college students not be subjected to “the violence of the word” because many of them “are away from home for the first time and at a vulnerable stage of psychological development.” If they’re targeted and the university does nothing to help them, they will be “left to their own resources in coping with the damage wrought.” That might have, she wrote, “lifelong repercussions.”20

Perhaps. But Ms. Matsuda doesn’t seem to have considered the possibility that insulating students could also make them, well, insular. A few weeks ago, Zineb El Rhazoui, a journalist at Charlie Hebdo, spoke at the University of Chicago, protected by the security guards she has traveled with since supporters of the Islamic State issued death threats against her. During the question-and-answer period, a Muslim student stood up to object to the newspaper’s apparent disrespect for Muslims and to express her dislike of the phrase “I am Charlie.”21

Ms. El Rhazoui replied, somewhat irritably, “Being Charlie Hebdo means to die because of a drawing,” and not everyone has the guts to do that (although she didn’t use the word guts). She lives under constant threat, Ms. El Rhazoui said. The student answered that she felt threatened, too.22

A few days later, a guest editorialist in the student newspaper took Ms. El Rhazoui to task. She had failed to ensure “that others felt safe enough to express dissenting opinions.” Ms. El Rhazoui’s “relative position of power,” the writer continued, had granted her a “free pass to make condescending attacks on a member of the university.” In a letter to the editor, the president and the vice president of the University of Chicago French Club, which had sponsored the talk, shot back, saying, “El Rhazoui is an immigrant, a woman, Arab, a human-rights activist who has known exile, and a journalist living in very real fear of death. She was invited to speak precisely because her right to do so is, quite literally, under threat.”23

You’d be hard-pressed to avoid the conclusion that the student and her defender had burrowed so deep inside their cocoons, were so overcome by their own fragility, that they couldn’t see that it was Ms. El Rhazoui who was in need of a safer space.24

![]() AT ISSUE: HOW FREE SHOULD FREE SPEECH BE?

AT ISSUE: HOW FREE SHOULD FREE SPEECH BE?

- What are “safe spaces”? According to Shulevitz, what is the problem of designating “some spaces as safe” (para. 7)?

- In paragraph 9, Shulevitz quotes Adam Shapiro, a student, who says, “I don’t see how you can have a therapeutic space that’s also an intellectual space.” What does Shapiro mean? Do you agree with him?

- Does Shulevitz use inductive or deductive reasoning to make her case? Why do you think that she chose this strategy?

- Where does Shulevitz discuss arguments against her position? Does she present these arguments fairly? Explain.

- Does Shulevitz appeal mainly to ethos, pathos, or logos?

- In paragraph 17, Shulevitz says, “Only a few of the students want stronger anti-hate-speech codes.” Does this admission undercut her argument? Why or why not?

This essay was posted on Slate.com on February 12, 2015.

ERIC POSNER

UNIVERSITIES ARE RIGHT TO CRACK DOWN ON SPEECH AND BEHAVIOR

Lately, a moral panic about speech and sexual activity in universities has reached a crescendo. Universities have strengthened rules prohibiting offensive speech typically targeted at racial, ethnic, and sexual minorities; taken it upon themselves to issue “trigger warnings” to students when courses offer content that might upset them; banned sexual acts that fall short of rape under criminal law but are on the borderline of coercion; and limited due process protections of students accused of violating these rules.1

Most liberals celebrate these developments, yet with a certain uneasiness. Few of them want to apply these protections to society at large. Conservatives and libertarians are up in arms. They see these rules as an assault on free speech and individual liberty. They think universities are treating students like children. And they are right. But they have also not considered that the justification for these policies may lie hidden in plain sight: that students are children. Not in terms of age, but in terms of maturity. Even in college, they must be protected like children while being prepared to be adults.2

There is a popular, romantic notion that students receive their university education through free and open debate about the issues of the day. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Students who enter college know hardly anything at all—that’s why they need an education. Classroom teachers know students won’t learn anything if they blab on about their opinions. Teachers are dictators who carefully control what students say to one another. It’s not just that sincere expressions of opinion about same-sex marriage or campaign finance reform are out of place in chemistry and math class. They are out of place even in philosophy and politics classes, where the goal is to educate students (usually about academic texts and theories), not to listen to them spout off. And while professors sometimes believe there is pedagogical value in allowing students to express their political opinions in the context of some text, professors (or at least, good professors) carefully manipulate their students so that the discussion serves pedagogical ends.3

That’s why the contretemps about a recent incident at Marquette University is far less alarming than libertarians think. An inexperienced instructor was teaching a class on the philosophy of John Rawls, and a student in the class argued that same-sex marriage was consistent with Rawls’ philosophy. When another student told the teacher outside of class that he disagreed, the teacher responded that she would not permit a student to oppose same-sex marriage in class because that might offend gay students.4

While I believe that the teacher mishandled the student’s complaint, she was justified in dismissing it. The purpose of the class was to teach Rawls’ theory of justice, not to debate the merits of same-sex marriage. The fact that a student injected same-sex marriage into the discussion does not mean that the class was required to discuss it. The professor might reasonably have believed that the students would gain a better understanding of Rawls’ theory if they thought about how it applied to issues less divisive and hence less likely to distract students from the academic merits of the theory.5

Teaching is tricky. Everyone understands that a class is a failure if students refuse to learn because they feel bullied or intimidated, or if ideological arguments break out that have nothing to do with understanding an idea. It is the responsibility of the professor to conduct the class in such a way that maximal learning occurs, not maximal speech. That’s why no teacher would permit students to launch into anti-Semitic diatribes in a class about the Holocaust, however sincerely the speaker might think that Jews were responsible for the Holocaust or the Holocaust did not take place. And even a teacher less scrupulous about avoiding offense to gay people would draw a line if a student in the Rawls class wanted to argue that Jim Crow or legalization of pedophilia is entailed by the principles of justice. While advocates of freedom of speech like to claim that falsehoods get squeezed out in the “marketplace of ideas,” in classrooms they just receive an F.6

“It is the responsibility of the professor to conduct the class in such a way that maximal learning occurs, not maximal speech.”

Most of the debate about speech codes, which frequently prohibit students from making offensive comments to one another, concerns speech outside of class. Two points should be made. First, students who are unhappy with the codes and values on campus can take their views to forums outside of campus—to the town square, for example. The campus is an extension of the classroom, and so while the restrictions in the classroom are enforced less vigorously, the underlying pedagogical objective of avoiding intimidation remains intact.7

Second, and more important—at least for libertarian partisans of the free market—the universities are simply catering to demand in the marketplace for education. While critics sometimes give the impression that lefty professors and clueless administrators originated the speech and sex codes, the truth is that universities adopted them because that’s what most students want. If students want to learn biology and art history in an environment where they needn’t worry about being offended or raped, why shouldn’t they? As long as universities are free to choose whatever rules they want, students with different views can sort themselves into universities with different rules. Indeed, students who want the greatest speech protections can attend public universities, which (unlike private universities) are governed by the First Amendment. Libertarians might reflect on the irony that the private market, in which they normally put faith, reflects a preference among students for speech restrictions.8

And this brings me to the most important overlooked fact about speech and sex code debates. Society seems to be moving the age of majority from 18 to 21 or 22. We are increasingly treating college-age students as quasi-children who need protection from some of life’s harsh realities while they complete the larval stage of their lives. Many critics of these codes discern this transformation but misinterpret it. They complain that universities are treating adults like children. The problem is that universities have been treating children like adults.9