The Elements of Argument

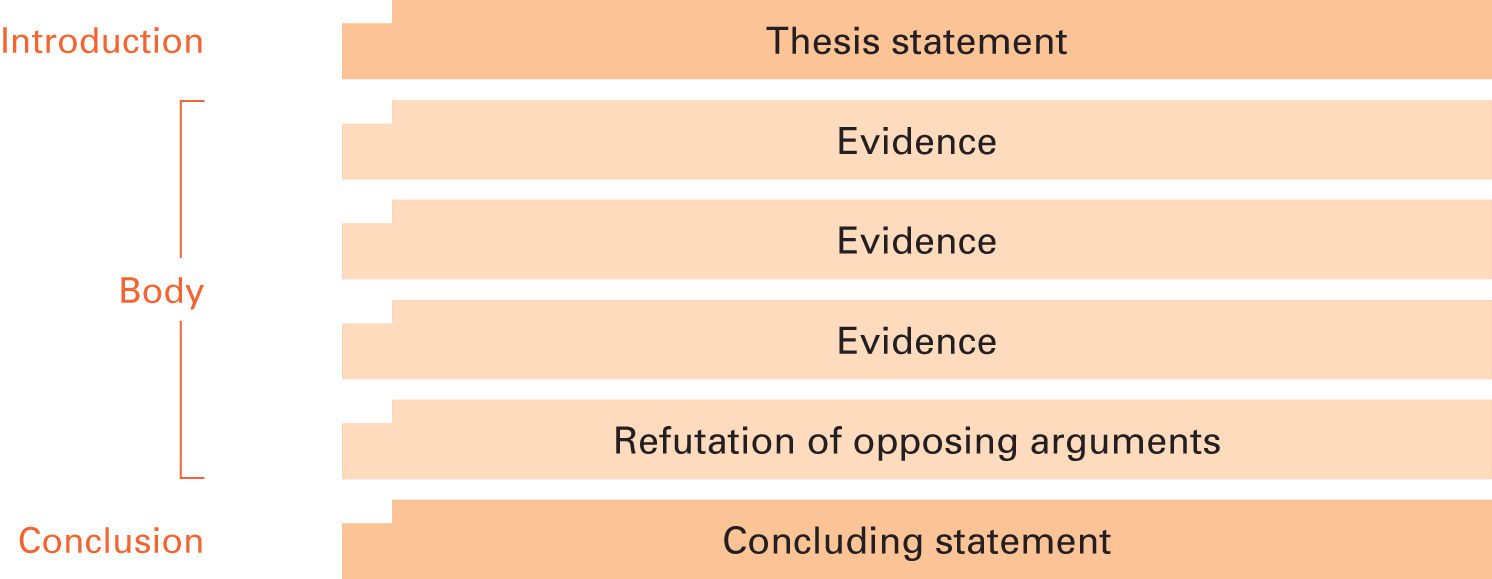

An argumentative essay includes the same three sections—introduction, body, and conclusion —as any other essay. In an argumentative essay, however, the introduction includes an argumentative thesis statement, the body includes both the supporting evidence and the refutation of opposing arguments, and the conclusion includes a strong, convincing concluding statement that reinforces the position stated in the thesis.

The following diagram illustrates one way to organize an argumentative essay.

The elements of an argumentative essay are like the pillars of an ancient Greek temple. Together, the four elements—thesis statement, evidence, refutation of opposing arguments, and concluding statement—help you build a strong argument.

Ancient Greek temple

AP Photo/Alessandro Fucarini

Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a single sentence that states your position on an issue. An argumentative essay must have an argumentative thesis —one that takes a firm stand. For example, on the issue of whether colleges should require all students to study a language other than English, your thesis statement could be any of the following (and other positions are also possible):

Colleges should require all students to study a foreign language.

Colleges should require all liberal arts majors to study a foreign language.

Colleges should require all students to take Spanish, Chinese, or Farsi.

Colleges should not require any students to study a foreign language.

An argumentative thesis must be debatable —that is, it must have at least two sides, stating a position with which some reasonable people might disagree. To confirm that your thesis is debatable, you should see if you can formulate an antithesis, or opposing argument. For example, the statement, “Our school has a foreign-language requirement” has no antithesis because it is simply a statement of fact; you could not take the opposite position because the facts would not support it. However, the following thesis statement takes a position that is debatable (and therefore suitable for an argumentative thesis):

| THESIS | Our school should institute a foreign-language requirement. |

| ANTITHESIS | Our school should not institute a foreign-language requirement. |

(For more on thesis statements, see Chapter 7.)

Evidence

Evidence is the material—facts, observations, expert opinion, examples, statistics, and so on—that supports your thesis statement. For example, you could support your position that foreign-language study should be required for all college students by arguing that this requirement will make them more employable, and you could cite employment statistics to support this point. Alternatively, you could use the opinion of an expert on the topic—for example, an experienced college language instructor—to support the opposite position, arguing that students without an interest in language study are wasting their time in such courses.

You will use both facts and opinions to support the points you make in your arguments. A fact is a statement that can be verified (proven to be true). An opinion is always open to debate because it is simply a personal judgment. Of course, the more knowledgeable the writer is, the more credible his or her opinion is. Thus, the opinion of a respected expert on language study will carry more weight than the opinion of a student with no particular expertise on the issue. However, if the student’s opinion is supported by facts, it will be much more convincing than an unsupported opinion.

FACTS

Some community colleges have no foreign-language requirements.

Some selective liberal arts colleges require all students to take two years or more of foreign-language study.

At some universities, undergraduates must take as many as fourteen foreign-language credits.

Some schools grant credit for high school language classes, allowing these courses to fulfill the college foreign-language requirement.

UNSUPPORTED OPINIONS

Foreign-language courses are not as important as math and science courses.

Foreign-language study should be a top priority on university campuses.

Engineering majors should not have to take a foreign-language course.

It is not fair to force all students to study a foreign language.

SUPPORTED OPINIONS

The university requires all students to take a full year of foreign-language study, but it is not doing enough to support those who need help. For example, it does not provide enough student tutors, and the language labs have no evening hours.

According to Ruth Fuentes, chair of the Spanish department, nursing and criminal justice majors who take at least two years of Spanish have an easier time finding employment after graduation than students in those majors who do not study Spanish.

Refutation

Because every argument has more than one side, you should not assume that your readers will agree with you. On the contrary, readers usually need to be convinced that your position on an issue has merit. This means that you need to do more than just provide sufficient evidence in support of your position; you also need to refute (disprove or call into question) arguments that challenge your position, possibly acknowledging the strengths of those opposing arguments and then pointing out their shortcomings. For example, if you take a position in favor of requiring foreign-language study for all college students, some readers might argue that college students already have to take too many required courses. After acknowledging the validity of this argument, you could refute it by pointing out that a required foreign-language course would not necessarily be a burden for students because it could replace another, less important required course. (For more on refutation, see Chapter 7.)

Concluding Statement

After you have provided convincing support for your position and refuted opposing arguments, you should end your essay with a strong concluding statement that reinforces your position. (The position that you want readers to remember is the one stated in your thesis, not the opposing arguments that you have refuted.) For example, you might conclude an essay in support of a foreign-language requirement by making a specific recommendation or by predicting the possible negative outcome of not implementing this requirement.

![]() The following student essay includes all four of the elements that are needed to build a convincing argument.

The following student essay includes all four of the elements that are needed to build a convincing argument.

EXERCISE 1.1

EXERCISE 1.1

The following essay, “Raise the Drinking Age to Twenty-Five,” by Andrew Herman, includes all four of the basic elements of argument discussed so far. Read the essay, and then answer the questions that follow it, consulting the diagram on page 24 if necessary.

This commentary appeared on August 22, 2007, on BG Views, a website for Bowling Green State University and the citizens of its community.

ANDREW HERMAN

RAISE THE DRINKING AGE TO TWENTY-FIVE

As a new school year begins, as dorms fill with new and returning students alike, a single thought frequents the minds of every member of our population: newfound freedom from a summer of jobs and familial responsibilities.1

But our return to school coexists with a possibly lethal counterpart: college drinking.2

Nearly everyone is exposed to parties during college, and one would be hard pressed to find a college party without alcohol. Most University students indicate in countless surveys they have used alcohol in a social setting before age 21.3

“It is startling just how ineffective current laws have been.”

It is startling just how ineffective current laws have been at curbing underage drinking.4

A dramatic change is needed in the way society addresses drinking and the way we enforce existing laws, and it can start with a simple change: making the drinking age 25.5

Access and availability are the principal reasons underage drinking has become easy to do. Not through direct availability, but through access to legal-aged “friends.”6

In a college setting, it is all but impossible not to know a person who is older than 21 and willing to provide alcohol to younger students. Even if unintentional, there is no verification that each person who drinks is of the appropriate age.7

However, it should be quite easy to ensure underage individuals don’t have access to alcohol. In reality, those who abstain from alcohol are in the minority. Countless people our age consider speeding tickets worse than an arrest for underage consumption.8

Is it truly possible alcohol abuse has become so commonplace, so acceptable, that people forget the facts?9

Each year, 1,400 [college students] die from drinking too much. 600,000 are victims of alcohol-related physical assault and 17,000 are a result of drunken driving deaths, many being innocent bystanders.10

Perhaps the most disturbing number: 70,000 people, overwhelmingly female, are annually sexually assaulted in alcohol-related situations.11

These numbers are difficult to grasp for the sheer prevalence of alcoholic destruction. Yet, we, as college students, are responsible for an overwhelming portion of their incidence. It is difficult to imagine anyone would wish to assume the role of rapist, murderer, or victim. We all assume these things could never happen to us, but I am certain victims in these situations thought the same. The simple truth is that driving under the influence is the leading cause of death for teens. For 10- to 24-year-olds, alcohol is the fourth-leading cause of death, made so by factors ranging from alcohol poisoning to alcohol-related assault and murder.12

For the sake of our friends, those we love, our futures, and ourselves, we must take a stand and we must do it now.13

Advocates of lowering the drinking age assert only four countries worldwide maintain a “21 standard,” and a gradual transition to alcohol is useful in reducing the systemic social problems of substance abuse.14

If those under the age of 21 are misusing alcohol, it makes little sense to grant free rein to those individuals to use it legally. A parent who observes their children abusing the neighbor’s dog would be irresponsible to get one of their own without altering such dangerous behavior.15

Increasing the drinking age will help in the search for solutions to grievous alcoholic problems, making it far more difficult in college environments to find legal-aged providers.16

By the time we are 25, with careers and possibly families of our own, there is no safety net to allow us to have a “Thirsty Thursday.” But increasing the legal age is not all that needs to be done. Drinking to get drunk needs to exist as a social taboo rather than a doorway to popularity.17

Peer pressure can become a tool to change this. What once was a factor greatly contributing to underage drinking can now become an instrument of good, seeking to end such a dangerous practice as excessive drinking. Laws on drinking ages, as any other law, need to be enforced with the energy and vigor each of us should expect.18

Alcohol is not an inherently evil poison. It does have its place, as do all things in the great scheme of life.19

But with alcohol comes the terrible risk of abuse with consequences many do not consider. All too often, these consequences include robbing someone of his life or loved one. All communities in the country, our own included, have been touched by such a tragedy.20

Because of this, and the hundreds of thousands of victims each year in alcohol-related situations, I ask that you consider the very real possibility of taking the life of another due to irresponsible drinking.21

If this is not enough, then take time to think, because that life could very well be your own.22

Identifying the Elements of Argument

What is this essay’s thesis? Restate it in your own words.

List the arguments Herman presents as evidence to support his thesis.

Summarize the opposing argument the essay identifies. Then, summarize Herman’s refutation of this argument.

Restate the essay’s concluding statement in your own words.

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

READING AND WRITING ABOUT THE ISSUE

Is a College Education Worth the Money?

Butch Dill/AP Photos

Reread the At Issue box on page 23, which summarizes questions raised on both sides of this issue. As the following sources illustrate, reasonable people may disagree about this controversial topic.

As you review the sources, you will be asked to answer some questions and to complete some simple activities. This work will help you understand both the content and the structure of the sources. When you have finished, you will be ready to write an essay in which you take a position on the topic “Is a College Education Worth the Money?”

SOURCES

David Leonhardt, “Is College Worth It? Clearly, New Data Say,” p. 33

David Leonhardt, “Is College Worth It? Clearly, New Data Say,” p. 33 Marty Nemko, “We Send Too Many Students to College,” p. 37

Marty Nemko, “We Send Too Many Students to College,” p. 37 Jennie Le, “What Does It Mean to Be a College Grad?,” p. 41

Jennie Le, “What Does It Mean to Be a College Grad?,” p. 41 Dale Stephens, “College Is a Waste of Time,” p. 43

Dale Stephens, “College Is a Waste of Time,” p. 43 Bridget Terry Long, “College Is Worth It—Some of the Time,” p. 45

Bridget Terry Long, “College Is Worth It—Some of the Time,” p. 45 Mary C. Daly and Leila Bengali, “Is It Still Worth Going to College?,” p. 48

Mary C. Daly and Leila Bengali, “Is It Still Worth Going to College?,” p. 48

This essay appeared in the New York Times on May 27, 2014.

DAVID LEONHARDT

IS COLLEGE WORTH IT? CLEARLY, NEW DATA SAY

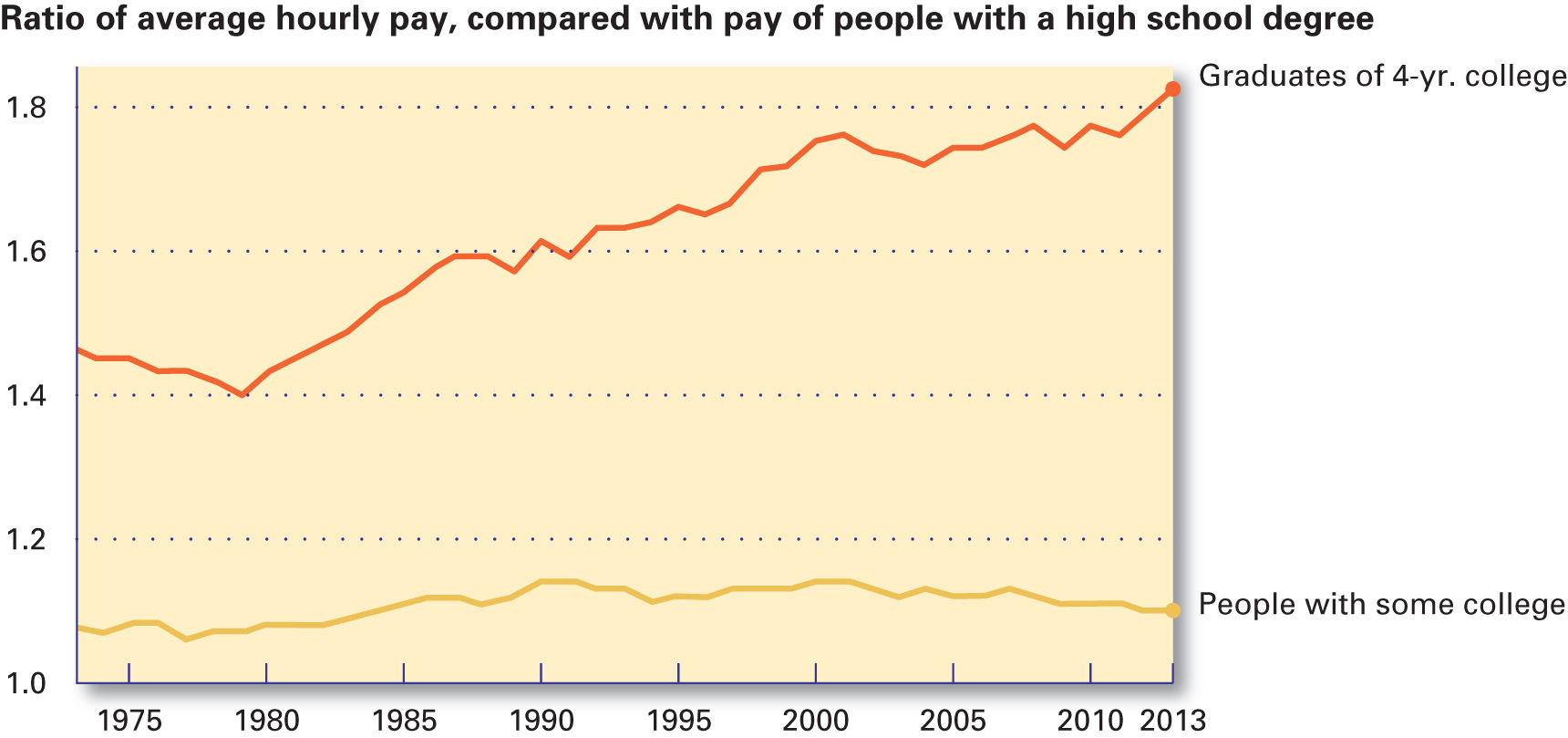

Rising Value of a College Degree

The pay of people with a four-year college degree has risen compared to that of those with a high school degree but no college credit. The relative pay of people who attended college without earning a four-year degree has stayed flat.1

Labels reflect group’s highest level of education. “Graduates of 4-year college,” for instance, excludes people with graduate degrees.

Data from: New York Times analysis of Economic Policy Institute data

The image shows a line graph where Y-axis represents ratio of average hourly pay of people with some college, and graduates of 4-year college. It is divided in four intervals with a difference of 0.2 each, namely: 1.0–1.2, 1.2–1.4, 1.4–1.6, and 1.6–1.8. X-axis represents time period from 1975 to 2010, divided in equal intervals of 5 years, ending at year 2013. There are two separate curves for two categories. The lower curve depicts average hourly pay of “people with some college”, and the higher curve depicts average hourly pay of “graduates of 4-year college.” The line graph depicting average hourly pay of people with some college is at 1.09 in 1975, fluctuates up over the years to reach about 1.16 in the year 1990, stays almost stable at this level with some fluctuations, and comes down to about 1.1 in the year 2013. The line graph depicting average hourly pay of people who are graduates of 4-year college degree starts at about 1.48 in the year 1970, dips to 1.4 in the year 1980, rises again to reach 1.6 in the late 1980s, and with some slight fluctuations over the years, keeps on rising. The next major rise is achieved at 1.78 in the year 2000, after which there was a slight downfall to 1.7 in the year 2005, and then again an upward trend to reach 1.82 in the year 2013. So, the average hourly wage for graduates of 4-year college people starts not only at a higher level (1.48) as compared to people with some college (1.09), after almost 30 years, graduates of 4 year college end with higher average hourly pay (1.82), as compared to (1.1) for people with some college degree.

Some newly minted college graduates struggle to find work. Others accept jobs for which they feel overqualified. Student debt, meanwhile, has topped $1 trillion.2

It’s enough to create a wave of questions about whether a college education is still worth it.3

A new set of income statistics answers those questions quite clearly: Yes, college is worth it, and it’s not even close. For all the struggles that many young college graduates face, a four-year degree has probably never been more valuable.4

The pay gap between college graduates and everyone else reached a record high last year, according to the new data, which is based on an analysis of Labor Department statistics by the Economic Policy Institute in Washington. Americans with four-year college degrees made 98 percent more an hour on average in 2013 than people without a degree. That’s up from 89 percent five years earlier, 85 percent a decade earlier, and 64 percent in the early 1980s.5

The pay of people with a four-year college degree has risen compared to that of those with a high school degree but no college credit. The relative pay of people who attended college without earning a four-year degree has stayed flat.6

There is nothing inevitable about this trend. If there were more college graduates than the economy needed, the pay gap would shrink. The gap’s recent growth is especially notable because it has come after a rise in the number of college graduates, partly because many people went back to school during the Great Recession. That the pay gap has nonetheless continued growing means that we’re still not producing enough of them.7

“We have too few college graduates,” says David Autor, an M.I.T. economist, who was not involved in the Economic Policy Institute’s analysis. “We also have too few people who are prepared for college.”8

It’s important to emphasize these shortfalls because public discussion today—for which we in the news media deserve some responsibility—often focuses on the undeniable fact that a bachelor’s degree does not guarantee success. But of course it doesn’t. Nothing guarantees success, especially after 15 years of disappointing economic growth and rising inequality.9

When experts and journalists spend so much time talking about the limitations of education, they almost certainly are discouraging some teenagers from going to college and some adults from going back to earn degrees. (Those same experts and journalists are sending their own children to college and often obsessing over which one.) The decision not to attend college for fear that it’s a bad deal is among the most economically irrational decisions anybody could make in 2014.10

The much-discussed cost of college doesn’t change this fact. According to a paper by Mr. Autor published Thursday in the journal Science, the true cost of a college degree is about negative $500,000. That’s right: Over the long run, college is cheaper than free. Not going to college will cost you about half a million dollars.11

“Not going to college will cost you about half a million dollars.”

Mr. Autor’s paper—building on work by the economists Christopher Avery and Sarah Turner—arrives at that figure first by calculating the very real cost of tuition and fees. This amount is then subtracted from the lifetime gap between the earnings of college graduates and high school graduates. After adjusting for inflation and the time value of money, the net cost of college is negative $500,000, roughly double what it was three decades ago.12

This calculation is necessarily imprecise, because it can’t control for any pre-existing differences between college graduates and nongraduates—differences that would exist regardless of schooling. Yet other research, comparing otherwise similar people who did and did not graduate from college, has also found that education brings a huge return.13

In a similar vein, the new Economic Policy Institute numbers show that the benefits of college don’t go just to graduates of elite colleges, who typically go on to earn graduate degrees. The wage gap between people with only a bachelor’s degree and people without such a degree has also kept rising.14

Tellingly, though, the wage premium for people who have attended college without earning a bachelor’s degree—a group that includes community college graduates—has not been rising. The big economic returns go to people with four-year degrees. Those returns underscore the importance of efforts to reduce the college dropout rate, such as those at the University of Texas, which Paul Tough described in a recent Times Magazine article.15

But what about all those alarming stories you hear about indebted, jobless college graduates?16

The anecdotes may be real, yet the conventional wisdom often exaggerates the problem. Among four-year college graduates who took out loans, average debt is about $25,000, a sum that is a tiny fraction of the economic benefits of college. (My own student debt, as it happens, was almost identical to this figure, in inflation-adjusted terms.) And the unemployment rate in April for people between 25 and 34 years old with a bachelor’s degree was a mere 3 percent.17

I find the data from the Economic Policy Institute especially telling because the institute—a left-leaning research group—makes a point of arguing that education is not the solution to all of the economy’s problems. That is important, too. College graduates, like almost everyone else, are suffering from the economy’s weak growth and from the disproportionate share of this growth flowing to the very richest households.18

The average hourly wage for college graduates has risen only 1 percent over the last decade, to about $32.60. The pay gap has grown mostly because the average wage for everyone else has fallen—5 percent, to about $16.50. “To me, the picture is people in almost every kind of job not being able to see their wages grow,” Lawrence Mishel, the institute’s president, told me. “Wage growth essentially stopped in 2002.”19

From the country’s perspective, education can be only part of the solution to our economic problems. We also need to find other means for lifting living standards—not to mention ways to provide good jobs for people without college degrees.20

But from almost any individual’s perspective, college is a no-brainer. It’s the most reliable ticket to the middle class and beyond. Those who question the value of college tend to be those with the luxury of knowing their own children will be able to attend it.21

Not so many decades ago, high school was considered the frontier of education. Some people even argued that it was a waste to encourage Americans from humble backgrounds to spend four years of life attending high school. Today, obviously, the notion that everyone should attend 13 years of school is indisputable.22

But there is nothing magical about 13 years of education. As the economy becomes more technologically complex, the amount of education that people need will rise. At some point, 15 years or 17 years of education will make more sense as a universal goal.23

That point, in fact, has already arrived.24

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

Paraphrase this essay’s thesis statement by filling in the following template.

Because________________________________________, a four-year college degree is now more important than ever.

- To support his position, Leonhardt relies largely on statistics. Where does he include other kinds of supporting evidence?

- Look at the graph that follows paragraph 1, and read its caption. What does this image add to the essay? Would Leonhardt’s argument have been as convincing without the graph? Why or why not?

- In paragraph 8, Leonhardt quotes economist David Autor. How do you suppose Marty Nemko (p. 37) would respond to Autor’s statements?

- In paragraph 16, Leonhardt asks a question to introduce an argument opposed to his position. What is this argument? Does he refute it effectively in the discussion that follows?

- In paragraph 22, Leonhardt begins his conclusion with an analogy. What two things is he comparing? What point is he making? Do you think this concluding strategy is effective? Why or why not? How else could he have ended his essay?

This undated essay is from MartyNemko.com.

MARTY NEMKO

WE SEND TOO MANY STUDENTS TO COLLEGE

Among my saddest moments as a career counselor is when I hear a story like this: “I wasn’t a good student in high school, but I wanted to prove to myself that I can get a college diploma—I’d be the first one in my family to do it. But it’s been six years and I still have 45 units to go.”1

I have a hard time telling such people the killer statistic: According to the U.S. Department of Education, if you graduated in the bottom 40 percent of your high school class and went to college, 76 of 100 won’t earn a diploma, even if given 8½ years. Yet colleges admit and take the money from hundreds of thousands of such students each year!2

Even worse, most of those college dropouts leave college having learned little of practical value (see below) and with devastated self-esteem and a mountain of debt. Perhaps worst of all, those people rarely leave with a career path likely to lead to more than McWages. So it’s not surprising that when you hop into a cab or walk into a restaurant, you’re likely to meet workers who spent years and their family’s life savings on college, only to end up with a job they could have done as a high school dropout.3

Perhaps yet more surprising, even the high school students who are fully qualified to attend college are increasingly unlikely to derive enough benefit to justify the often six-figure cost and four to eight years it takes to graduate—and only 40 percent of freshmen graduate in four years; 45 percent never graduate at all. Colleges love to trumpet the statistic that, over their lifetimes, college graduates earn more than nongraduates. But that’s terribly misleading because you could lock the college-bound in a closet for four years and they’d earn more than the pool of non-college-bound—they’re brighter, more motivated, and have better family connections. Too, the past advantage of college graduates in the job market is eroding: ever more students are going to college at the same time as ever more employers are offshoring ever more professional jobs. So college graduates are forced to take some very nonprofessional jobs. For example, Jill Plesnarski holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the private ($160,000 published total cost for four years) Moravian College. She had hoped to land a job as a medical research lab tech, but those positions paid so little that she opted for a job at a New Jersey sewage treatment plant. Today, although she’s since been promoted, she must still occasionally wash down the tower that holds raw sewage.4

Or take Brian Morris. After completing his bachelor’s degree in liberal arts from the University of California, Berkeley, he was unable to find a decent-paying job, so he went yet deeper into debt to get a master’s degree from the private Mills College. Despite those degrees, the best job he could land was teaching a three-month-long course for $3,000. At that point, Brian was married and had a baby, so to support them, he reluctantly took a job as a truck driver. Now Brian says, “I just have to get out of trucking.”5

Colleges are quick to argue that a college education is more about enlightenment than employment. That may be the biggest deception of all. There is a Grand Canyon of difference between what the colleges tout in their brochures and websites and the reality.6

Colleges are businesses, and students are a cost item while research is a profit center. So colleges tend to educate students in the cheapest way possible: large lecture classes, with small classes staffed by rock-bottom-cost graduate students and, in some cases, even by undergraduate students. Professors who bring in big research dollars are almost always rewarded, while even a fine teacher who doesn’t bring in the research bucks is often fired or relegated to the lowest rung: lecturer.7

“Colleges are businesses, and students are a cost item.”

So, no surprise, in the definitive Your First College Year nationwide survey conducted by UCLA researchers (data collected in 2005, reported in 2007), only 16.4 percent of students were very satisfied with the overall quality of instruction they received and 28.2 percent were neutral, dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied. A follow-up survey of seniors found that 37 percent reported being “frequently bored in class,” up from 27.5 percent as freshmen.8

College students may be dissatisfied with instruction, but despite that, do they learn? A 2006 study funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts found that 50 percent of college seniors failed a test that required them to do such basic tasks as interpret a table about exercise and blood pressure, understand the arguments of newspaper editorials, or compare credit card offers. Almost 20 percent of seniors had only basic quantitative skills. For example, the students could not estimate if their car had enough gas to get to the gas station.9

What to do? Colleges, which receive billions of tax dollars with minimum oversight, should be held at least as accountable as companies are. For example, when some Firestone tires were defective, the government nearly forced it out of business. Yet year after year, colleges turn out millions of defective products: students who drop out or graduate with far too little benefit for the time and money spent. Yet not only do the colleges escape punishment; they’re rewarded with ever greater taxpayer-funded student grants and loans, which allow colleges to raise their tuitions yet higher.10

What should parents and guardians do?11

- If your student’s high school grades and SAT or ACT are in the bottom half of his high school class, resist colleges’ attempts to woo him. Their marketing to your child does not indicate that the colleges believe he will succeed there. Colleges make money whether or not a student learns, whether or not she graduates, and whether or not he finds good employment. If a physician recommended a treatment that cost a fortune and required years of effort without disclosing the poor chances of it working, she’d be sued and lose in any court in the land. But colleges—one of America’s most sacred cows—somehow seem immune.12

So let the buyer beware. Consider nondegree options:13

- Apprenticeship programs (a great portal to apprenticeship websites: www.khake.com/page58.html)

- Short career-preparation programs at community colleges

- The military

- On-the-job training, especially at the elbow of a successful small business owner

- Let’s say your student is in the top half of his high school class and is motivated to attend college by more than the parties, being able to say she went to college, and the piece of paper. Then have her apply to perhaps a dozen colleges. Colleges vary less than you might think, yet financial aid awards can vary wildly. It’s often wise to choose the college that requires you to pay the least cash and take on the smallest loan. College is among the few products where you don’t get what you pay for—price does not indicate quality.14

- If your child is one of the rare breed who, on graduating high school, knows what he wants to do and isn’t unduly attracted to college academics or the Animal House environment that college dorms often are, then take solace in the fact that in deciding to forgo college, he is preceded by scores of others who have successfully taken that noncollege road less traveled. Examples: the three most successful entrepreneurs in the computer industry, Bill Gates, Michael Dell, and Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak, all do not have a college degree. Here are some others: Malcolm X, Rush Limbaugh, Barbra Streisand, PBS NewsHour’s Nina Totenberg, Tom Hanks, Maya Angelou, Ted Turner, Ellen DeGeneres, former governor Jesse Ventura, IBM founder Thomas Watson, architect Frank Lloyd Wright, former Israeli president David Ben-Gurion, Woody Allen, Warren Beatty, Domino’s pizza chain founder Tom Monaghan, folksinger Joan Baez, director Quentin Tarantino, ABC-TV’s Peter Jennings, Wendy’s founder Dave Thomas, Thomas Edison, Blockbuster Video founder and owner of the Miami Dolphins Wayne Huizenga, William Faulkner, Jane Austen, McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc, Oracle founder Larry Ellison, Henry Ford, cosmetics magnate Helena Rubinstein, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Graham Bell, Coco Chanel, Walter Cronkite, Walt Disney, Bob Dylan, Leonardo DiCaprio, cookie maker Debbi Fields, Sally Field, Jane Fonda, Buckminster Fuller, DreamWorks cofounder David Geffen, Roots author Alex Haley, Ernest Hemingway, Dustin Hoffman, famed anthropologist Richard Leakey, airplane inventors Wilbur and Orville Wright, Madonna, satirist H. L. Mencken, Martina Navratilova, Rosie O’Donnell, Nathan Pritikin (Pritikin diet), chef Wolfgang Puck, Robert Redford, oil billionaire John D. Rockefeller, Eleanor Roosevelt, NBC mogul David Sarnoff, and seven U.S. presidents from Washington to Truman.15

- College is like a chain saw. Only in certain situations is it the right tool. Encourage your child to choose the right tool for her post-high school experience.16

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

- Which of the following statements best summarizes Nemko’s position? Why?

“We Send Too Many Students to College” (title)

“There is a Grand Canyon of difference between what the colleges tout in their brochures and websites and the reality” (para. 6).

“Colleges, which receive billions of tax dollars with minimum oversight, should be held at least as accountable as companies are” (10).

“College is like a chain saw. Only in certain situations is it the right tool” (16).

- Where does Nemko support his thesis with appeals to logic? Where does he appeal to the emotions? Where does he use an appeal to authority? Which of these three kinds of appeals do you find the most convincing? Why?

- List the arguments Nemko uses to support his thesis in paragraphs 2–4.

- In paragraph 4, Nemko says, “Colleges love to trumpet the statistic that, over their lifetimes, college graduates earn more than nongraduates.” In paragraph 6, he says, “Colleges are quick to argue that a college education is more about enlightenment than employment.” How does he refute these two opposing arguments? Are his refutations effective?

- Nemko draws an analogy between colleges and businesses, identifying students as a “cost item” (7). Does this analogy—including his characterization of weak students as “defective products” (10)—work for you? Why or why not?

- What specific solutions does Nemko propose for the problem he identifies? To whom does he address these suggestions—and, in fact, his entire argument?

- Reread paragraph 15. Do you think the list of successful people who do not hold college degrees is effective support for Nemko’s position? What kind of appeal does this paragraph make? How might you refute its argument?

This personal essay is from talk.onevietnam.org, where it appeared on May 9, 2011.

JENNIE LE

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE A COLLEGE GRAD?

After May 14th, I will be a college graduate. By fall, there will be no more a cappella rehearsals, no more papers or exams, no more sleepless nights, no more weekday drinking, no more 1 am milk tea runs, no more San Francisco Bay Area exploring. I won’t be with the people I now see daily. I won’t have the same job with the same awesome boss. I won’t be singing under Sproul every Monday. I won’t be booked with weekly gigs that take me all over California. I won’t be lighting another VSA Culture Show.1

I will also have new commitments: weekly dinner dates with my mom, brother/sister time with my other two brothers, job hunting and career building, car purchasing and maintenance. In essence, my life will be—or at least feel—completely different. From what college alumni have told me, I will soon miss my college days after they are gone.2

But in the bigger picture, outside of the daily tasks, what does it mean to hold a college degree? My fellow graduating coworker and I discussed the importance (or lack thereof) of our college degrees: while I considered hanging up my two diplomas, she believed that having a bachelor’s was so standard and insubstantial, only a professional degree is worth hanging up and showing off. Nowadays, holding a college degree (or two) seems like the norm; it’s not a very outstanding feat.3

“Nowadays, holding a college degree (or two) seems like the norm.”

However, I’d like to defend the power of earning a college degree. Although holding a degree isn’t as powerful as it was in previous decades, stats still show that those who earn bachelor’s degrees are likely to earn twice as much as those who don’t. Also, only 27 percent of Americans can say they have a bachelor’s degree or higher. Realistically, having a college degree will likely mean a comfortable living and the opportunity to move up at work and in life.4

Personally, my degrees validate my mother’s choice to leave Vietnam. She moved here for opportunity. She wasn’t able to attend college here or in Vietnam or choose her occupation. But her hard work has allowed her children to become the first generation of Americans in the family to earn college degrees: she gave us the ability to make choices she wasn’t privileged to make. Being the fourth and final kid to earn my degree in my family, my mom can now boast about having educated children who are making a name for themselves (a son who is a computer-superstar, a second son and future dentist studying at UCSF, another son who is earning his MBA and manages at Mattel, and a daughter who is thankful to have three brothers to mooch off of).5

For me, this degree symbolizes my family being able to make and take the opportunities that we’ve been given in America, despite growing up with gang members down my street and a drug dealer across from my house. This degree will also mean that my children will have more opportunities because of my education, insight, knowledge, and support.6

Even though a college degree isn’t worth as much as it was in the past, it still shows that I—along with my fellow graduates and the 27 percent of Americans with a bachelor’s or higher—will have opportunities unheard of a generation before us, showing everyone how important education is for our lives and our futures.7

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

What purpose do the first two paragraphs of this essay serve? Do you think they are necessary? Do you think they are interesting? How else could Le have opened her essay?

Where does Le state her thesis? Do you think she should have stated it more forcefully? Can you suggest a more effectively worded thesis statement for this essay?

In paragraph 3, Le summarizes an opposing argument. Paraphrase this argument. How does she refute it? Can you think of other arguments against her position that she should have addressed?

In paragraphs 5–6, Le includes an appeal to the emotions. Does she offer any other kind of supporting evidence? If so, where? What other kinds of evidence do you think she should include? Why?

Echoing a point she made in paragraph 4, Le begins her conclusion with “Even though a college degree isn’t worth as much as it was in the past, …” Does this concluding statement undercut her argument, or is the information presented in paragraph 4 enough to address this potential problem?

This essay appeared on CNN.com on June 3, 2011.

DALE STEPHENS

COLLEGE IS A WASTE OF TIME

I have been awarded a golden ticket to the heart of Silicon Valley: the Thiel Fellowship. The catch? For two years, I cannot be enrolled as a full-time student at an academic institution. For me, that’s not an issue; I believe higher education is broken.1

I left college two months ago because it rewards conformity rather than independence, competition rather than collaboration, regurgitation rather than learning, and theory rather than application. Our creativity, innovation, and curiosity are schooled out of us.2

Failure is punished instead of seen as a learning opportunity. We think of college as a stepping-stone to success rather than a means to gain knowledge. College fails to empower us with the skills necessary to become productive members of today’s global entrepreneurial economy.3

College is expensive. The College Board Policy Center found that the cost of public university tuition is about 3.6 times higher today than it was 30 years ago, adjusted for inflation. In the book Academically Adrift, sociology professors Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa say that 36 percent of college graduates showed no improvement in critical thinking, complex reasoning, or writing after four years of college. Student loan debt in the United States, unforgivable in the case of bankruptcy, outpaced credit card debt in 2010 and will top $1 trillion in 2011.4

Fortunately, there are productive alternatives to college. Becoming the next Mark Zuckerberg or mastering the phrase “Would you like fries with that?” are not the only options.5

“Fortunately, there are productive alternatives to college.”

The success of people who never completed or attended college makes us question whether what we need to learn is taught in school. Learning by doing—in life, not classrooms—is the best way to turn constant iteration into true innovation. We can be productive members of society without submitting to academic or corporate institutions. We are the disruptive generation creating the “free agent economy” built by entrepreneurs, creatives, consultants, and small businesses envisioned by Daniel Pink in his book, A Whole New Mind: Why Right Brainers Will Rule the Future.6

We must encourage young people to consider paths outside college. That’s why I’m leading UnCollege: a social movement empowering individuals to take their education beyond the classroom. Imagine if millions of my peers copying their professors’ words verbatim started problem-solving in the real world. Imagine if we started our own companies, our own projects, and our own organizations. Imagine if we went back to learning as practiced in French salons, gathering to discuss, challenge, and support each other in improving the human condition.7

A major function of college is to signal to potential employers that one is qualified to work. The Internet is replacing this signaling function. Employers are recruiting on LinkedIn, Facebook, StackOverflow, and Behance. People are hiring on Twitter, selling their skills on Google, and creating personal portfolios to showcase their talent. Because we can document our accomplishments and have them socially validated with tools such as LinkedIn Recommendations, we can turn experiences into opportunity. As more and more people graduate from college, employers are unable to discriminate among job seekers based on a college degree and can instead hire employees based on their talents.8

Of course, some people want a formal education. I do not think everyone should leave college, but I challenge my peers to consider the opportunity cost of going to class. If you want to be a doctor, going to medical school is a wise choice. I do not recommend keeping cadavers in your garage. On the other hand, what else could you do during your next 50-minute class? How many e-mails could you answer? How many lines of code could you write?9

Some might argue that college dropouts will sit in their parents’ basements playing Halo 2, doing Jell-O shots, and smoking pot. These are valid but irrelevant concerns, for the people who indulge in drugs and alcohol do so before, during, and after college. It’s not a question of authorities; it’s a question of priorities. We who take our education outside and beyond the classroom understand how actions build a better world. We will change the world regardless of the letters after our names.10

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

- In paragraph 1, Stephens says, “I believe higher education is broken.” Is this statement his essay’s thesis? Explain.

- List Stephens’s criticisms of college education.

- Why does Stephens begin by introducing himself as a winner of a Thiel Fellowship? Is this introductory strategy an appeal to logos, ethos, or pathos? Explain.

- List the evidence that Stephens uses to support his position. Do you think this essay needs more supporting evidence? If so, what kind of support would you suggest Stephens add?

- In paragraphs 9 and 10, Stephens considers possible arguments against his thesis. What are these opposing arguments? Does he refute them effectively?

- Throughout this essay, Stephens uses the pronoun we (as well as the pronoun I). Do these first-person pronouns refer to college students in general? To certain kinds of students? To Thiel fellows? Explain.

This article first appeared in the online publication “Examining the Value of a College Degree,” produced by PayScale.

BRIDGET TERRY LONG

COLLEGE IS WORTH IT—SOME OF THE TIME

Is it still worthwhile to attend college? This has been a constant question, and as an economist and higher education researcher, I can wholeheartedly say yes. The data are clear: individuals with at least some college education make more money than those with only a high school degree. And let us not forget about the non-monetary returns, such as better working conditions, lower rates of disability, and increased civic engagement.1

However, the conversation has become more complicated as research has pointed to another important fact: yes, college is worth it, but not always. We no longer think that all educations are financially good investments—the specifics matter. The answer for any student depends upon three important factors: the college attended, the field of study, and the cost or debt taken.2

“We no longer think that all educations are financially good investments—the specifics matter.”

First, the college a student attends makes a difference, as we can see from the Payscale data. But these recent data underscore a longer-term trend. In a 1999 study, a co-author and I documented increasing inequality among college-educated workers.1 While those near the top of the income distribution (i.e., the 90th percentile) experienced larger returns to their educations over time, after accounting for inflation, those near the bottom of the distribution (i.e., the 10th percentile) earned less in 1995 than 1972. Our examination of the reasons behind these changes highlights the important role of increasing segregation in higher education, where the top students have become more and more concentrated at institutions with much greater resources. The colleges rated “most competitive” often spend more than three times per student than “less competitive” colleges.3

However, selectivity rating alone does not necessarily predict which schools have the highest rates of student success. A 2009 study documents the fact that graduation rates differ not only by college selectivity but also within a selectivity group. For example, among colleges rated as “very competitive,” six-year graduation rates averaged from 30 percent for the bottom 10 schools to 82 percent for the top 10 schools.2 Selectivity does not necessarily guarantee high levels of degree completion.4

A large part of the problem to understanding which colleges are good investments is the lack of good measures of college quality. Most existing measures rely heavily on the academic achievements of students before they even step foot on the college campus. Meanwhile, there are few measures of the quality of the postsecondary learning experience or the value-added to the student. Hence, we rely on indicators such as earnings and loan default rates. While it is helpful to have this information to establish minimum thresholds of what might be a financially worthwhile education, they are not sufficient to help students compare possible colleges and make the decision about where they, as individuals, might maximize their benefits.5

The second thing that increasingly matters in college investments is the field of study. While many students do not work in the field of their college major, typically, students majoring in engineering and the sciences reap the largest benefits. However, income is not the only thing that varies by major: as emphasized by the Great Recession, unemployment rates also differ by field of study. Interestingly, although education majors may not make the most money, they have among the lowest unemployment rates.6

The first two factors, the chosen college and major, focus on potential benefits, but those benefits must be compared to costs to determine whether a college education is worthwhile. We focus most of our attention on price and debt load as a measure of the burden of college costs. Debt is a reality of higher education today, and some debt is fine if it makes possible a beneficial educational investment. However, the level of debt that is reasonable depends greatly on the school attended and major. One might judge $10,000 of total debt for an engineering degree to be fine, while the opposite would be true for a six-week certificate program.7

Unfortunately, students typically have such poor counseling on how much debt is appropriate given their plans, and with large levels of unmet financial need, many turn to multiple sources of debt, such as credit cards and private loans, without fully understanding how this will affect them over the longer term. Moreover, recent graduates (or dropouts) fresh out of school have little appreciation for how their investments may pay off 10 years from now when their current reality is living at home with their parents. In other words, it’s difficult to internalize long-term benefits when the costs are so heavily weighed up front.8

Ultimately, knowing whether college is a good investment depends on which college, which major, at what price (or debt). Looking at the averages is no longer as meaningful, given the importance of match for an individual student with specific interests, talents, and resources. And while I would underscore the fact that for the vast majority of students, most combinations of college/major/debt they would choose are worthwhile investments, we have reached a time when the benefits of college may not far exceed the costs for increasing numbers of students.9

Even if only a small percentage of investments are “bad”—ones in which the college attended has low levels of success and gives credentials with little value while making students take out large amounts of debt—we have reached an enrollment level in which a small percentage translates into thousands and thousands of students each year. And that is a problem that cannot be ignored.10

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

- In paragraph 1, Long introduces herself as “an economist and higher education researcher.” Why do you think she does this? Is she appealing here to logos, ethos, or pathos?

- Long begins her essay with a question. What attitude toward college tuition does she assume her readers have? How can you tell? How else might she have opened her discussion?

- According to Long, in what sense has “the conversation [about whether college is a worthwhile investment] become more complicated” (para. 2)? What “three important factors” does she consider?

- Outline the structure of this essay, filling in the template below with Long’s thesis statement and key points.

Thesis statement:

Support

First important factor: _______________________________

Second important factor: _______________________________

Third important factor: ________________________________

- In paragraphs 9 and 10, what does Long conclude about the value of a college education? What reservations does she have? How does the discussion in these paragraphs answer the question she asks in paragraph 1?

- Could Long’s entire essay be seen as a refutation of the position she takes in the essay’s first paragraph? Explain.

- If Long were making recommendations about how to solve the “problem that cannot be ignored” (10), what do you think she might recommend?

This economic letter was originally posted by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco at www.frbsf.org, where it appeared on May 5, 2014.

MARY C. DALY AND LEILA BENGALI

IS IT STILL WORTH GOING TO COLLEGE?

Media accounts documenting the rising cost of a college education and relatively bleak job prospects for new college graduates have raised questions about whether a four-year college degree is still the right path for the average American. In this Economic Letter, we examine whether going to college remains a worthwhile investment. Using U.S. survey data, we compare annual labor earnings of college graduates with those of individuals with only a high school diploma. The data show college graduates outearn their high school counterparts as much as in past decades. Comparing the earnings benefits of college with the costs of attending a four-year program, we find that college is still worth it. This means that, for the average student, tuition costs for the majority of college education opportunities in the United States can be recouped by age 40, after which college graduates continue to earn a return on their investment in the form of higher lifetime wages.1

Earnings Outcomes by Educational Attainment

A common way to track the value of going to college is to estimate a college earnings premium, which is the amount college graduates earn relative to high school graduates. We measure earnings for each year as the annual labor income for the prior year, adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index (CPI-U), reported in 2011 dollars. The earnings premium refers to the difference between average annual labor income for high school and college graduates. We use data on household heads and partners from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID). The PSID is a longitudinal study that follows individuals living in the United States over a long time span. The survey began in 1968 and now has more than 40 years of data including educational attainment and labor market income. To focus on the value of a college degree relative to less education, we exclude people with more than a fouryear degree.2

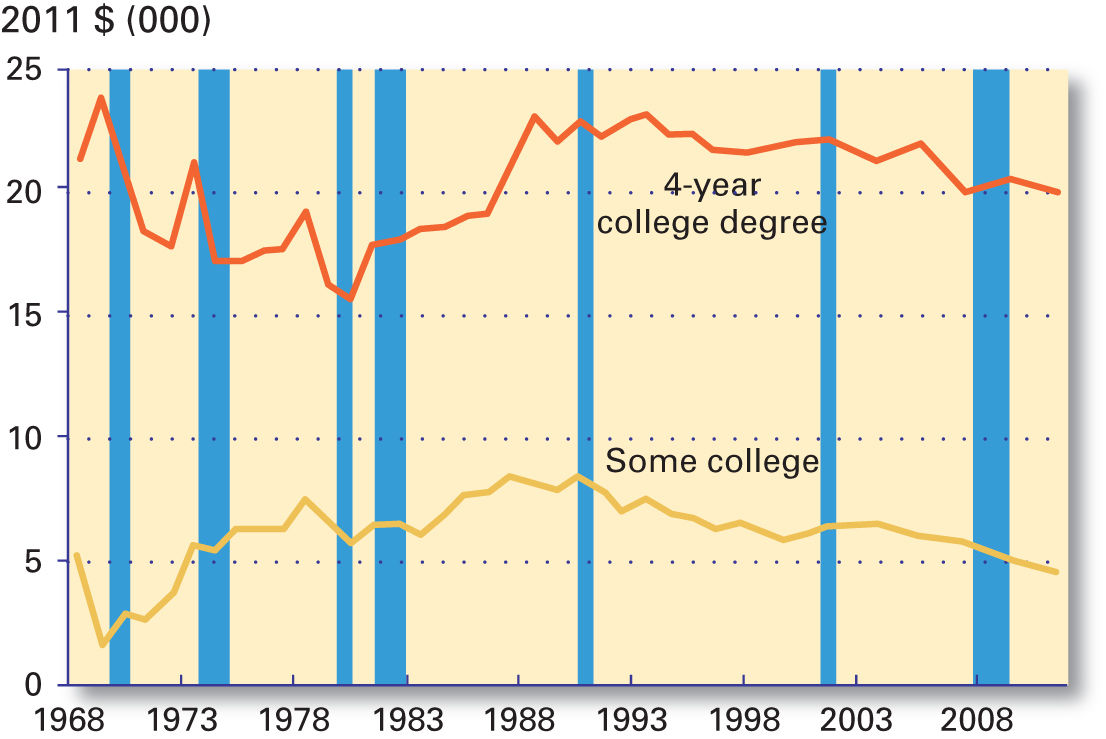

Figure 1 shows the earnings premium relative to high school graduates for individuals with a four-year college degree and for those with some college but no four-year degree. The payoff from a degree is apparent. Although the premium has fluctuated over time, at its lowest in 1980 it was about $15,750, meaning that individuals with a four-year college degree earned about 43 percent more on average than those with only a high school degree. In 2011, the latest data available in our sample, college graduates earned on average about $20,050 (61 percent) more per year than high school graduates. Over the entire sample period the college earnings premium has averaged about $20,300 (57 percent) per year. The premium is much smaller, although not zero, for workers with some college but no four-year degree.3

Figure 1: Earnings Premium over High School Education

Data from: PSID and authors’ calculations. Premium defined as difference in mean annual labor income. Blue bars denote NBER recession dates.

A graph is depicting showing earnings premium over high school education during the time period of 1968 to 2008. X-axis represents time period, with intervals of 5 years, starting from 1968 up to 2008. The Y-axis represents earnings premium starting from $0, and reaching up to $25,000, with an interval of 5,000 US dollars. There are two line graphs. The lower line graph depicts earnings premium of those people with some college degree. The upper graph depicts earnings premium of those people who have 4 year college degree. The earnings premium for people with 4-year college degree starts at around $21,000 in the year 1968, and attains its peak at $23,500 in the year 1971, dips again and reaches its lowest level at $15,500 in the year 1981. It starts rising again and attain its peak at $23,000 in the year 1991, and starts dipping again to reach $20,000 after year 2008. The earnings premium of those people with some college starts at $5,000 in the year 1968, dips to $3,000 in the year 1970, rises again to $5,500 in the year 1974. It reaches a new peak at $7,000 in the year 1978, dips again to $6,000 in 1980, to rise again and reach peak at $8,500 in 1991. After this, line graph falls continuously to reach $4,500 after the year 2008. The image also has seven vertical blue bars that denote NBER recession dates. These recession dates are shown as during 1969-1970, 1973-1975, 1980-1982, 1990-1991, 2001, and 2007-2009.

A potential shortcoming of the results in Figure 1 is that they combine the earnings outcomes for all college graduates, regardless of when they earned a degree. This can be misleading if the value from a college education has varied across groups from different graduation decades, called “cohorts.” To examine whether the college earnings premium has changed from one generation to the next, we take advantage of the fact that the PSID follows people over a long period of time, which allows us to track college graduation dates and subsequent earnings.4

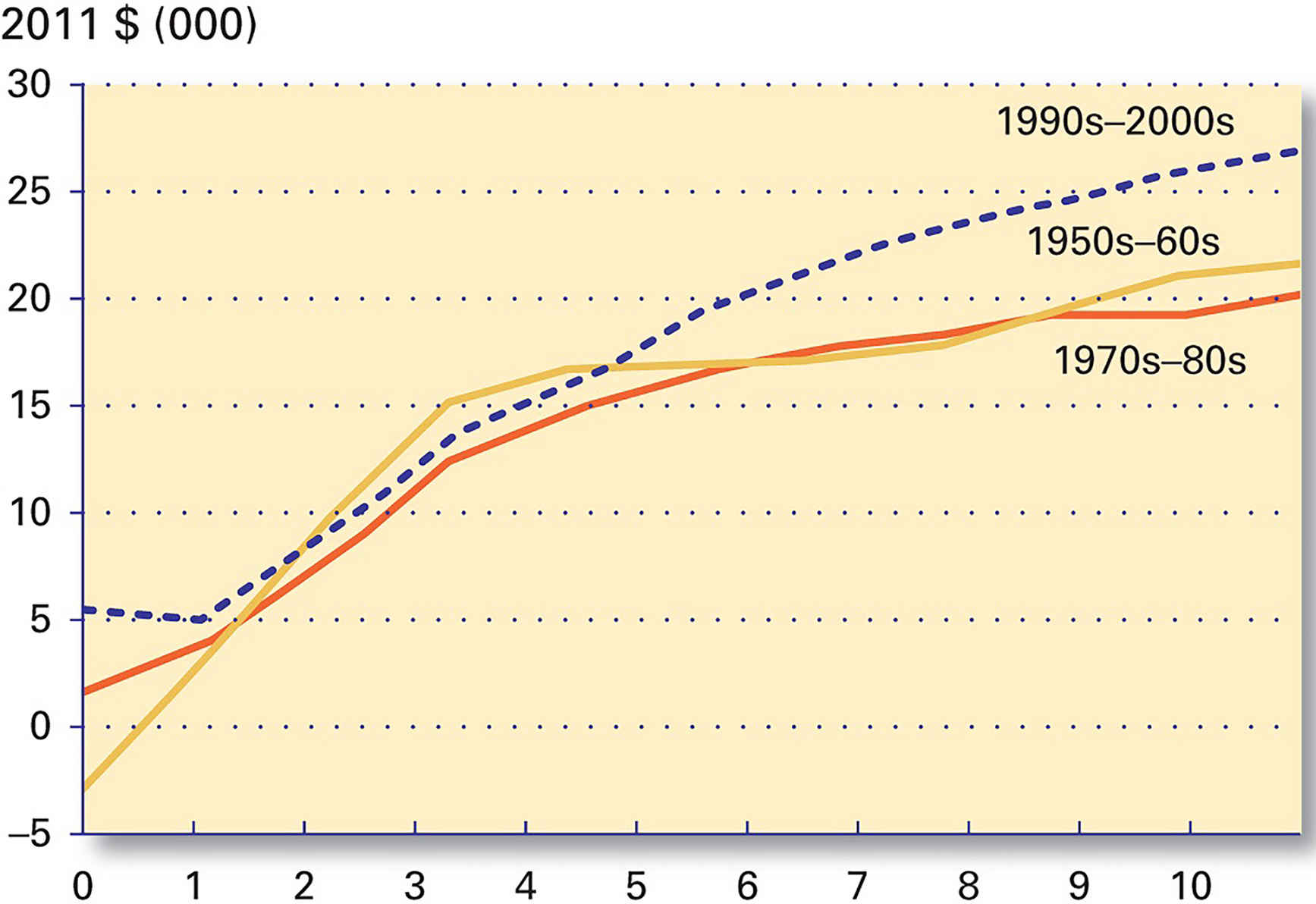

Using these data we compute the college earnings premium for three college graduate cohorts, namely those graduating in the 1950s-60s, the 1970s-80s, and the 1990s-2000s. The premium measures the difference between the average annual earnings of college graduates and high school graduates over their work lives. To account for the fact that high school graduates gain work experience during the four years they are not in college, we compare earnings of college graduates in each year since graduation to earnings of high school graduates in years since graduation plus four. We also adjust the estimates for any large annual fluctuations by using a three-year centered moving average, which plots a specific year as the average of earnings from that year, the year before, and the year after.5

Figure 2 shows that the college earnings premium has risen consistently across cohorts. Focusing on the most recent college graduates (1990s-2000s) there is little evidence that the value of a college degree has declined over time, and it has even risen somewhat for graduates five to ten years out of school.6

Years since graduation from college

Data from: PSID and authors’ calculations. Premium defined as difference in mean annual labor income of college graduates in each year since graduation and earnings of high school graduates in years since graduation plus four. Values are three-year centered moving averages of annual premiums.

A graphical representation of college earnings premium by graduation decades, as per the data collected in 2011. The X-axis represents “years since graduation from college”. It is divided into 10 intervals, that is, 0 to 1, 1 to 2, 2 to 3, 3 to 4, 4 to 5, 5 to 6, 6 to 7, 7 to 8, and 9 to 10. The Y-axis represents college earnings premium in thousands of US dollars, which is divided in seven equal intervals 5 to 0, 0 to 5, 5 to 10, 10 to 15, 15 to 20, 20to 25, and 25 to 30. The image shows the moving averages of college earning premium for three groups of people: (1) those who have done graduation in 1990s-2000s; (2) those who have done graduation in 1950s-1960s; and (3) those who have done graduation in 1970s-1980s. The approximate values of the three lines can be tabulated as follows:

| Years since graduation from college | College Earnings Premium (thousands US dollars) | ||

| 1990s-2000s | 1950s-60s | 1970s-80s | |

| 0 | 5.5 | -2.5 | 1 |

| 1 | 5 | 2.5 | 4 |

| 2 | 9 | 9 | 7 |

| 3 | 11 | 14 | 11 |

| 4 | 15 | 16 | 14 |

| 5 | 18 | 16 | 15.5 |

| 6 | 20 | 16.5 | 16 |

| 7 | 21 | 17 | 16 |

| 8 | 24 | 18 | 18.5 |

| 9 | 25 | 20 | 19 |

| 10 | 26 | 21 | 19.5 |

The figure also shows that the gap in earnings between college and high school graduates rises over the course of a worker’s life. Comparing the earnings gap upon graduation with the earnings gap 10 years out of school illustrates this. For the 1990s-2000s cohort the initial gap was about $5,400, and in 10 years this gap had risen to about $26,800. Other analysis confirms that college graduates start with higher annual earnings, indicated by an initial earnings gap, and experience more rapid growth in earnings than members of their age cohort with only a high school degree. This evidence tells us that the value of a college education rises over a worker’s life.7

Of course, some of the variation in earnings between those with and without a college degree could reflect other differences. Still, these simple estimates are consistent with a large and rigorous literature documenting the substantial premium earned by college graduates (Barrow and Rouse 2005, Card 2001, Goldin and Katz 2008, and Cunha, Karahan, and Soares 2011). The main message from these and similar calculations is that on average the value of college is high and not declining over time.8

Finally, it is worth noting that the benefits of college over high school also depend on employment, where college graduates also have an advantage. High school graduates consistently face unemployment rates about twice as high as those for college graduates, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. When the labor market takes a turn for the worse, as during recessions, workers with lower levels of education are especially hard-hit (Hoynes, Miller, and Schaller 2012). Thus, in good times and in bad, those with only a high school education face a lower probability of employment, on top of lower average earnings once employed.9

The Cost of College

Although the value of college is apparent, deciding whether it is worthwhile means weighing the value against the costs of attending. Indeed, much of the debate about the value of college stems not from the lack of demonstrated benefit but from the overwhelming cost. A simple way to measure the costs against the benefits is to find the breakeven amount of annual tuition that would make the average student indifferent between going to college versus going directly to the workforce after high school.10

“Although the value of college is apparent, deciding whether it is worthwhile means weighing the value against the costs of attending.”

To simplify the analysis, we assume that college lasts four years, students enter college directly from high school, annual tuition is the same all four years, and attendees have no earnings while in school. To focus on more recent experiences yet still have enough data to measure earnings since graduation, we use the last two decades of graduates (1990s and 2000s) and again smooth our estimates by using three-year centered moving averages.11

We calculate the cost of college as four years of tuition plus the earnings missed from choosing not to enter the workforce. To estimate what students would have received had they worked, we use the average annual earnings of a high school graduate zero, one, two, and three years since graduation.12

To determine the benefit of going to college, we use the difference between the average annual earnings of a college graduate with zero, one, two, three, and so on, years of experience and the average annual earnings of a high school graduate with four, five, six, seven, and so on years of experience. Because the costs of college are paid today but the benefits accrue over many future years when a dollar earned will be worth less, we discount future earnings by 6.67 percent, which is the average rate on an AAA bond from 1990 to 2011.13

With these pieces in place, we can calculate the breakeven amount of tuition for the average college graduate for any number of years; allowing more time to regain the costs will increase our calculated tuition ceiling.14

If we assume that accumulated earnings between college graduates and nongraduates will equalize 20 years after graduating from high school (at age 38), the resulting estimate for breakeven annual tuition would be about $21,200. This amount may seem low compared to the astronomical costs for a year at some prestigious institutions; however, about 90 percent of students at public four-year colleges and about 20 percent of students at private nonprofit four-year colleges faced lower annual inflation-adjusted published tuition and fees in 2013–14 (College Board 2013). Although some colleges cost more, there is no definitive evidence that they produce far superior results for all students (Dale and Krueger 2011).15

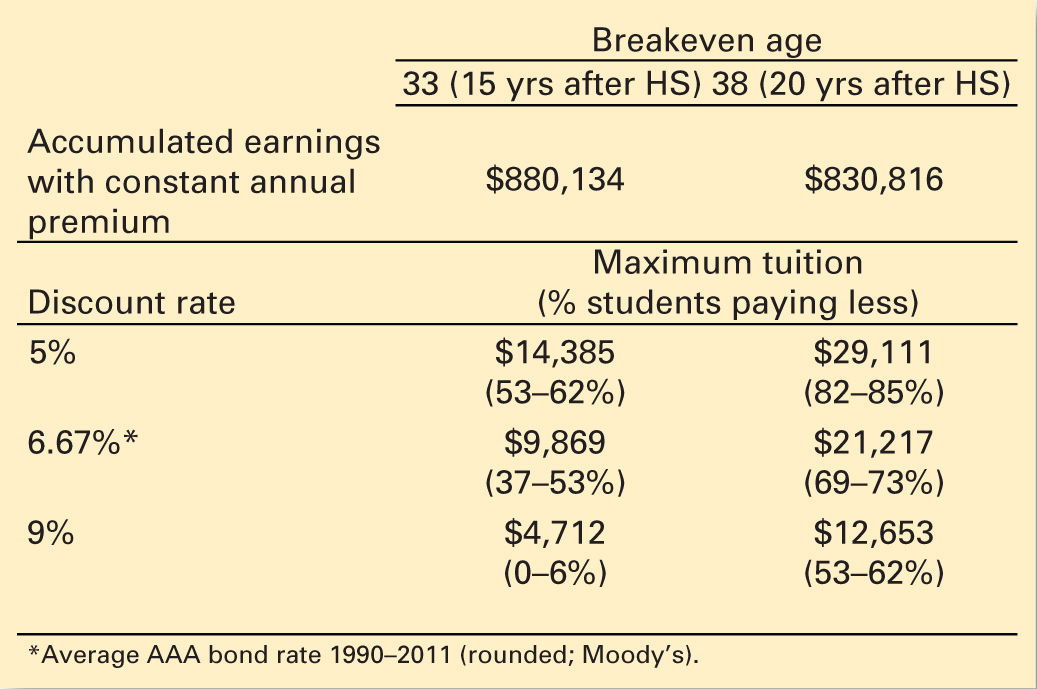

Table 1 shows more examples of maximum tuitions and the corresponding percent of students who pay less for different combinations of breakeven years and discount rates. Note that the tuition estimates are those that make the costs and benefits of college equal. So, tuition amounts lower than our estimates make going to college strictly better in terms of earnings than not going to college.16

Table 1: Maximum Tuitions by Breakeven Age and Discount Rates

Data from: PSID, College Board, and authors’ calculations. Premia held constant 15 or 20 years after high school (HS) graduation. Percent range gives lower and upper bounds of the percent of full-time undergraduates at four-year institutions who faced lower annual inflation-adjusted published tuition and fees in 2013–14.

Although other individual factors might affect the net value of a college education, earning a degree clearly remains a good investment for most young people. Moreover, once that investment is paid off, the extra income from the college earnings premium continues as a net gain to workers with a college degree. If we conservatively assume that the annual premium stays around $28,650, which is the premium 20 years after high school graduation for graduates in the 1990s-2000s, and accrues until the Social Security normal retirement age of 67, the college graduate would have made about $830,800 more than the high school graduate. These extra earnings can be spent, saved, or reinvested to pay for the college tuition of the graduate’s children.17

Conclusion

Although there are stories of people who skipped college and achieved financial success, for most Americans the path to higher future earnings involves a four-year college degree. We show that the value of a college degree remains high, and the average college graduate can recover the costs of attending in less than 20 years. Once the investment is paid for, it continues to pay dividends through the rest of the worker’s life, leaving college graduates with substantially higher lifetime earnings than their peers with a high school degree. These findings suggest that redoubling the efforts to make college more accessible would be time and money well spent.18

References

Barrow, L., and Rouse, C.E. (2005). “Does college still pay?” The Economist’s Voice 2(4), pp. 1–8.

Card, D. (2001). “Estimating the return to schooling: progress on some persistent econometric problems.” Econometrica 69(5), pp. 1127–1160.

College Board. (2013). “Trends in College Pricing 2013.”

Cunha, F., Karahan, F., and Soares, I. (2011). “Returns to Skills and the College Premium.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 43(5), pp. 39–86.

Dale, S., and Krueger, A. (2011). “Estimating the Return to College Selectivity over the Career Using Administrative Earnings Data.” NBER Working Paper 17159.

Goldin, C., and Katz, L. (2008). The Race between Education and Technology.

Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Hoynes, H., Miller, D., and Schaller, J. (2012). “Who Suffers During Recessions?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 26(3), pp. 27–48.

![]() AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

AT ISSUE: SOURCES FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

- Why does the title of this essay include the word “still”? What does still imply in this context?

- This essay is an “economic letter” from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and its language is more technical, and more mathand business-oriented, than that of the other readings in this chapter. In addition, this reading selection looks somewhat different from the others. What specific format features set this reading apart from others in the chapter?

- What kind of supporting evidence do the writers use? Do you think they should have included any other kinds of support—for example, expert opinion? Why or why not?

- In paragraph 10, the writers make a distinction between the “value of college” and the question of whether a college education is “worthwhile.” Explain the distinction they make here.

- For the most part, this report appeals to logos by presenting factual information. Does it also include appeals to pathos or ethos? If so, where? If not, should it have included these appeals?

TEMPLATE FOR STRUCTURING AN ARGUMENT

Write a one-paragraph argument in which you take a position on the topic of whether a college education is a good investment. Follow the template below, filling in the lines to create your argument.

Whether or not a college education is worth the money is a controversial topic. Some people believe that ___________________________________. Others challenge this position, claiming that ________________. However, ______________________________________. Although both sides of this issue have merit, it seems clear that a college education (is/is not) a worthwhile investment because ________________________________.

EXERCISE 1.2

EXERCISE 1.2

Interview two classmates on the topic of whether a college education is a worthwhile investment. Revise the one-paragraph argument that you drafted above so that it includes your classmates’ views on the issue.

EXERCISE 1.3

EXERCISE 1.3

Write an essay on the topic “Is a College Education Worth the Money?” Cite the readings on pages 33–54, and be sure to document your sources and to include a works-cited page. (See Chapter 10 for information on documenting sources.)

EXERCISE 1.4

EXERCISE 1.4

Review the four-point checklist on page 27, and apply each question to your essay. Does your essay include all four elements of an argumentative essay? Add any missing elements. Then, label your essay’s thesis statement, evidence, refutation of opposing arguments, and concluding statement.

EXERCISE 1.5

EXERCISE 1.5

Read the short essay that follows. What, if anything, do you think should be added to the writer’s discussion to make it more convincing? Should anything be deleted or changed? Incorporating what you have learned about the structure and content of an effective argument, write a one-paragraph response to the essay.

This essay appeared on Businessweek.com in March 2011.

TONY BRUMMEL

PRACTICAL EXPERIENCE TRUMPS FANCY DEGREES

So you got great grades and earned your bachelor’s degree? Congratulations. You may have been better off failing college and then starting a venture and figuring out why you didn’t pass your classroom tests.1

Being successful in business is absolutely not contingent on having a bachelor’s degree—or any other type of degree, for that matter. A do-or-die work ethic, passion, unwavering persistence, and vision mean more than anything that can be taught in a classroom. How many college professors who teach business have actually started a business?2

I am the sole owner of the top independent rock record label (according to Nielsen-published market share). Historically, the music industry is thought of as residing in New York City, Los Angeles, and Nashville. But I have blazed my own trail, segregating my business in its own petri dish here in Chicago. I started the business as a part-time venture in 1989 with $800 in seed capital. In 2009, Victory Records grossed $20 million. We’ve released more than 500 albums, including platinum-selling records for the groups Taking Back Sunday and Hawthorne Heights.3

“I have blazed my own trail.”

Because I never went to college and didn’t automatically have industry contacts, I had to learn all of the business fundamentals through trial and error when I started my own company. The skills I learned on my own have carried me through 20 years of business. Making mistakes forces one to learn.4

If you have a brand that people care about and loyal, hard-working employees coupled with a robust network of smart financial advisers, fellow entrepreneurs, and good legal backup, you will excel. There are plenty of people with degrees and MBAs who could read the books and earn their diplomas but cannot apply what they learned to building a successful enterprise.5

EXERCISE 1.6

EXERCISE 1.6

Study the image that opens this chapter. What argument could it suggest about the issue of whether a college education is worth the money?

1 Hoxby, Caroline and Bridget Terry Long. (1999) “Explaining Rising Inequality among the College-Educated.” National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 6873.

2 Hess, Frederick M., Mark Schneider, Kevin Carey, and Andrew P. Kelly. (2009) Diplomas and Dropouts: Which Colleges Actually Graduate Their Students (and Which Don’t). American Enterprise Institute.